Text by Tan Jia Yi

MuseSG Volume 11 Issue 1 - 2018

In Singapore’s transformation from quiet obscurity to fast-paced innovation, Kallang has consistently exemplified the spirit of “new and upcoming”. The area has a history of pioneering developments in Singapore, be it the tentative steps into the global economy or technological innovations like street lighting and aviation. The history of Kallang mirrors the broader evolution of Singapore with several aspects of its multi-faceted past forming a central part of our heritage. Many of the essential symbols of Singapore originate from Kallang – the Kallang River, the former National Stadium and of course, the iconic Kallang Wave cheer. Throughout the narrative of a relatively young Singapore, Kallang has played a fundamental role as a trailblazer of the nation.

Image courtesy of National Heritage Board.

The Origin of Kallang

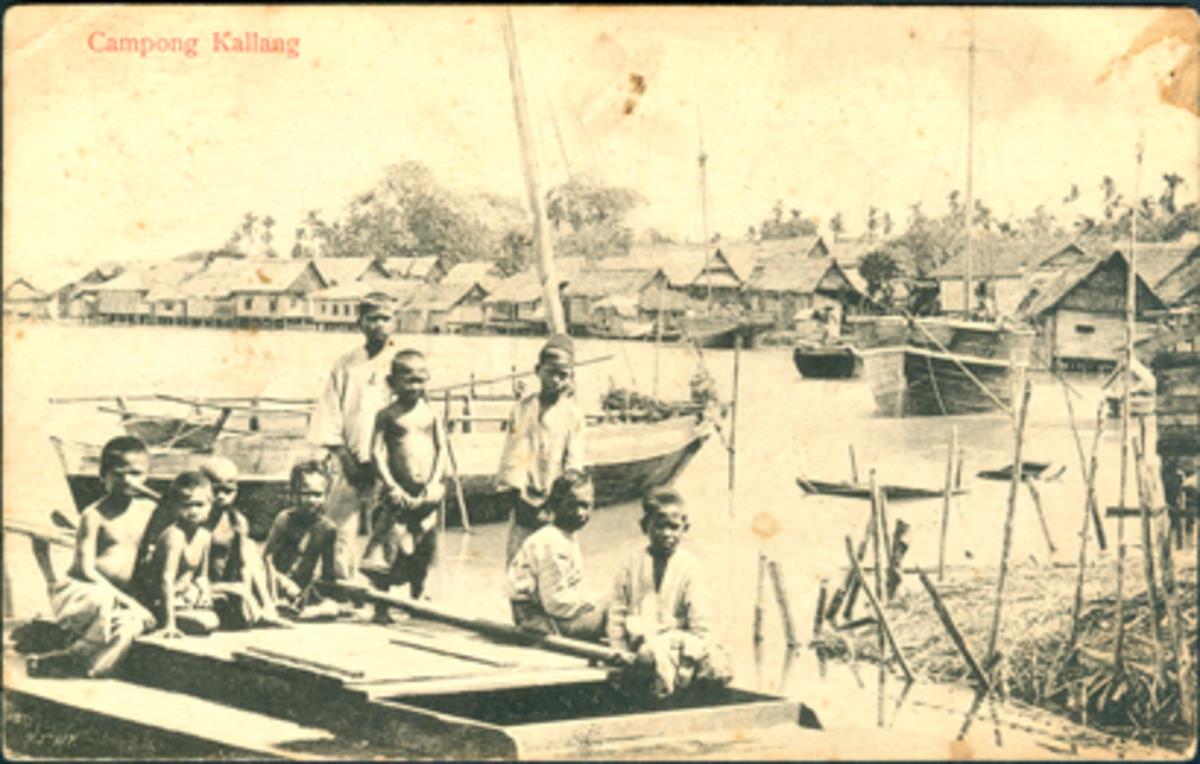

The name “Kallang” possibly derives from the Orang Kallang, a mobile community that was indigenous to the region, and who were living in Singapore before the British first arrived. The Orang Kallang were followers of the Temenggongs, or Malay chiefs who used to rule the area before the arrival of the British.1

The Orang Kallang lived along the river, subsisting on fishing and taking up various occupational roles that included producing rokok daun (a type of Malay palm leaf cigarette), providing water transportation, and gathering and selling wood for fuel.2 The Orang Kallang’s role in water transportation would inspire town planners more than a century later in their plans to increase the accessibility between Kallang and Bishan through the Kallang Waterway.

Lim Kheng Chye Collection, image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

After Singapore was formally ceded to the British in 1824, most of the Orang Kallang moved to the Pulai River in Johor where they remained under the jurisdiction of their Temenggong.3 Others moved to the offshore southern islands or to the Geylang area, as well as the northern coast of Singapore.4 In 1836, Dr William Montgomerie started Kallangdale, a large-scale sugarcane plantation located at the former Woodsville Road (now expunged). As similar European mega-plantations encroached into local settlements, Chinese immigrants who worked in these plantations also moved into Kallang and formed significant communities alongside local Malay villages.5 As in other parts of Singapore, the growing ethnic pluralism of Kallang, and the close proximity of different communities to each other, formed the basis of Singapore’s contemporary multicultural society.

The Glory of Forefront Development

By the 1830s, brick kilns had grown extensively in Kallang, overshadowing the sugar businesses there. This shift from sugar to bricks was a logical economic decision given the abundance of mud, easily retrieved from the nearby swamps. In 1858, brickmaking had become a colonial enterprise, and locally-produced bricks were recognised for their quality, winning awards at international events such as the 1867 Agra exhibition. Kallang’s brick kilns played a significant role in the construction of early towns in Singapore, paving the way for the further development of other settlements on the southern and western regions of Singapore.

Further trailblazing Singapore’s development into an urbanised nation was Kallang Gas Works, which lit up the streets of Singapore for the very first time in 1862.6 Gas lighting continued to be used extensively in Singapore until 1955, when it was gradually replaced by electricity.7 Kallang Gas Works supplied the nation with gas for more than a century until 1998 when it was replaced by Senoko Gas Works.8 CityGas, the company that managed Kallang Gas Works, also produced gas as common fuel for cooking, heating and drying applications in homes and commercial premises.

Image courtesy of the National Library Board, Singapore.

Kallang’s heritage of being the industrial powerhouse of Singapore is evident in the colloquialisms of the older generation, where Kallang is still remembered as huey sia. Meaning fire stronghold in Hokkien, huey sia aptly encapsulates the memories of many of its inhabitants, including that of long-time resident Seah Ah Kheng. Seah has lived in Kallang since the time of her birth in 1943, first in an attap hut and later on in a Housing & Development Board (HDB) flat.9 Slogging daily in the canteen of the gas works selling mixed rice, Seah witnessed the growth of Kallang from the time of post-war poverty and hunger to one which produced industrial innovations such as gas lighting. The Kallang Gas Works was a symbol of modernity and hope for a better future, but it too typified the anxieties of a changing landscape – locals harboured fears that the gas works would one day explode and engulf all that had been achieved thus far, literally transforming Kallang into a huey sia.

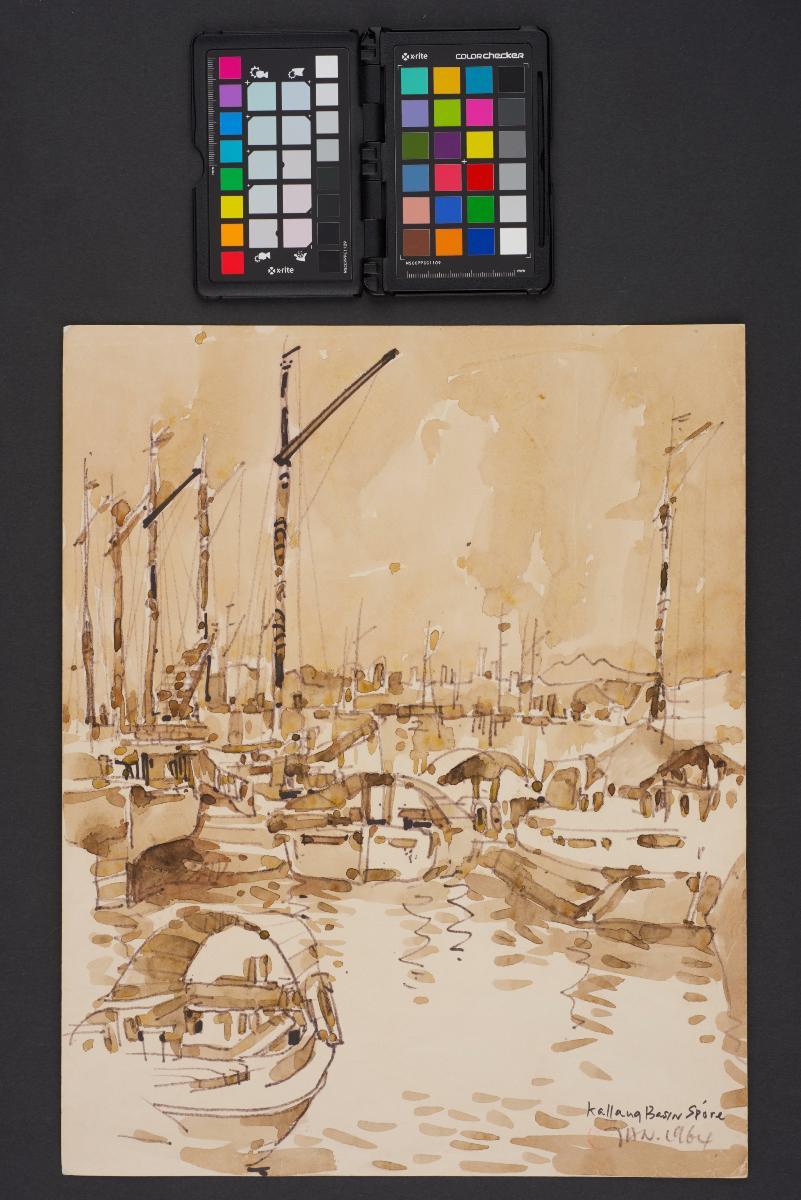

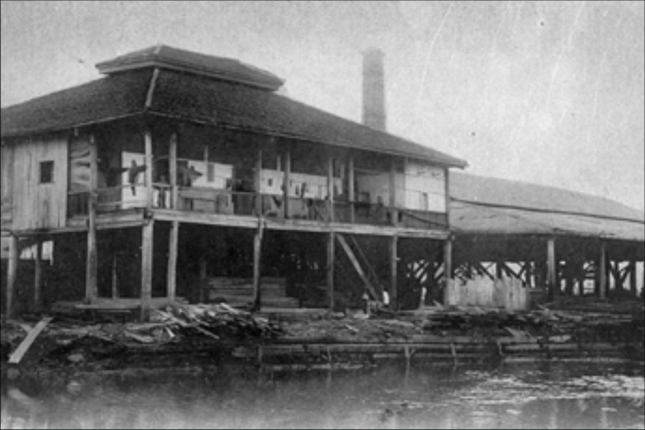

Kallang also became a key location for the regional timber industry. The waterways of the Kallang River attracted enterprises and individuals from the timber industry, including the largest enterprise in the colony – Singapore Steam Saw Mills, which was located along Kallang Road. Timber bought from the Malay Peninsula and the Indonesian islands was shipped via the sea and oated down the Kallang River to the mills that congregated near the Kallang River basin. These timber resources further bolstered Kallang’s role as a base of export for the wider region, shipping timber directly by steamer to all parts of the Far East, including Bangkok, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Peking – the major timber markets of the time. Thereafter, in the 1960s and 1970s, the sawmills received even more orders with an increasing global demand for regional timber products. Eventually, they moved out of Kallang and consolidated in the Sungei Kadut Industrial Estate in 1976.

Arshak C. Galstaun Collection, image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

One of the high points of Singapore’s development in the 20th century was the establishment of Kallang Airport in 1937. Due to its strategic location, Kallang had the honour of housing Singapore’s first commercial international airport building. Before Kallang, commercial air services had been handled by the Seletar military airbase. This new airport further connected Singapore to the rest of the world. Thanks to its advantageous location, Kallang Airport had become one of the largest and most important airports of the world during its prime from 1937 to the end of the 1940s.10 Costing nine million dollars, Kallang Airport was a crown jewel for the British Empire in Asia and was termed the “essence of modernity”. Famed pilot Amelia Earhart even described the new airport as an “aviation miracle of the East”, reiterating its unprecedented nature, and positioning it at the forefront of Singapore’s development. In 1955, Kallang Airport was replaced by the newly constructed Paya Lebar Airport which was better able to cope with increased traffic. Thereafter, the building played host to various other organisations, including the Singapore Youth Council Headquarters and the National Stadium.

Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore Collection, image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Ministry of Communication and Information Collection, image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Memory and Entertainment

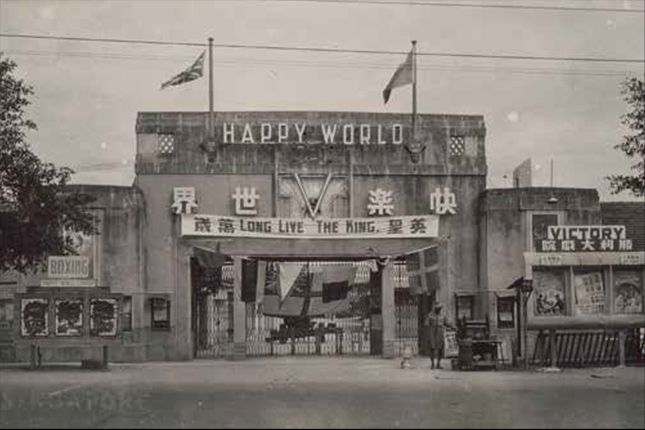

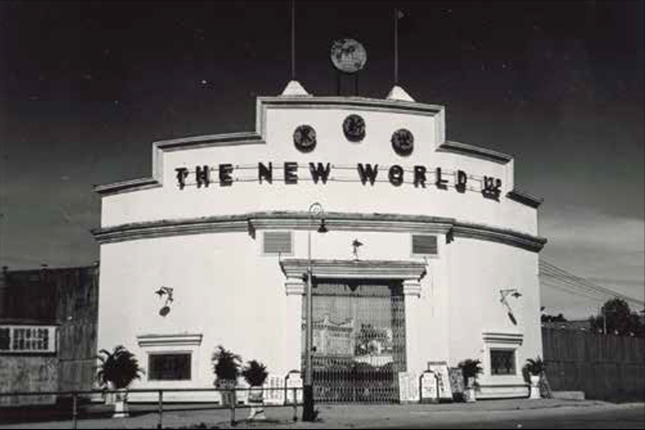

Within Singapore’s cultural and entertainment scene, Kallang paved the way with its amusement parks: New World in 1923 and Happy World (also known as Gay World) in 1936. These worlds formed the early strands of Singapore’s popular culture, housing dancing halls, amusement rides and iconic cabaret girls who danced to both Malay tunes and the Western foxtrot. The amusement parks were described as bustling with excitement, or using the Singlish creole term, they were “happening”. Seah fondly remembers: “Whenever we needed entertainment – to watch upcoming movies for five cents or Teochew opera – we went to Gay World”.11

Image courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Image courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

These amusement parks played a major role in pioneering Singapore’s music scene, attracting both local and regional musicians. Budding local artists including the Velvetones and The Quests were two of the acts that were fostered out of this environment. Notably, The Quests went on to produce “Shanty”, the first song by a local band to reach the top of the Singapore charts, displacing even The Beatles’ “I Should Have Known Better”.12 The song stayed at number one for over 10 weeks.13 Many of these bands were inspired by visiting bands such as Cliff Richards and The Shadows to venture into their own music. Andy Lim, a 75-year-old retired teacher who used to stay in Kallang, fondly recalls watching a concert at the National Stadium:

"The stadium was so crowded. But nobody bothered with the heat because the heat onstage was worse – in a good way! It was a fantastic, really hot show. That’s when every boy who saw Cliff Richard and The Shadows, in their resplendent suits and with those guitars, went: “I wanna be a band boy!”

Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore Collection, image courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The booming growth of home-grown musicians at these parks animated Singapore’s music scene, with Kallang at the centre of it all. Perhaps, it is this glorious era of Singaporean music that makes the amusement parks so nostalgic to the older generation, many of whom spent their younger days dancing the cha-cha.

The old National Stadium was the birthplace of a distinct Singaporean emblem – the Kallang Wave. During the legendary 1990 Malaysia Cup match against Perlis, the Singaporean coach hollered: “Untuk Bangsa Dan Negara! Majulah!”, roughly translating to “For country! Onward!”, to encourage the Singaporean football players.14 The shout evolved into a cheer aptly named the Kallang Wave as it was formed by spectators at National Stadium raising their arms in succession to simulate a wave. The match was a watershed win for Singapore, not only in football terms, but on a national level; the palpable passion of the audience, moving as one to the Kallang Wave, made history in that very moment. The Kallang Wave of 1990 set the precedence for many celebrations to come, where it would be repeated at events like the National Day Parade to unify Singaporeans in one movement.

Today, the National Stadium, Singapore Sports Hub and Kallang Wave Mall have continued this heritage of unifying Singaporeans. The Kallang Wave Mall, in particular, was timed to open on Singapore’s 50th birthday – a significant milestone in Singapore’s history. Former president of SMRT Desmond Kuek commented: “The Kallang Wave retains the association with the old National Stadium, and symbolises the distinctive spirit, energy and close community ties.” Similarly, the Sports Hub was built in 2014 to encourage a rejuvenation of sporting events and entertainment in Singapore in the spirit of the old National Stadium. Today, the Sports Hub continues the tradition of hosting regional sports events like the ASEAN Basketball League, as well as welcoming international entertainers such as The Script and Katy Perry. These efforts to refurbish and rebrand such sites represent a continuity of Kallang’s role in pioneering Singapore’s development as an entertainment hub. To this day, these sites in Kallang continue to revive and extend the tradition of exciting entertainment in Singapore.

The River Flows On

Renowned architect Jan Gehl remind us that there is a “continued need...[to create] great public spaces [to] sustain the soul and life of cities”.15 The Kallang River was a stream of life for over 200 years of Singapore’s history, and this persists to this day in the projects for recreation under the Active, Beautiful, Clean Waters (ABC) waterway.16 The Kallang River has revitalised its role in transportation, connecting Bishan to Kallang and increasing Kallang’s centrality. Although Kallang’s role as a trailblazer is now part of the history books, plans for the Kallang River and the new National Stadium continue to incorporate elements of its exciting past. The heritage of Kallang as a place blazing with fiery excitement, and which pioneered so many aspects of Singapore’s development, is one to be cherished, especially as the river of time flows on.

Image courtesy of National Heritage Board.

Notes