Text by Stefanie Tham

MuseSG Volume 8 Issue 2 - Jul to Sep 2015

A friendly debate comparing the western side of Singapore with the east went viral among netizens in early 2015, after a local Tumblr page was set up to poke fun at the west, which includes Jurong, Boon Lay, Pioneer, and Tuas. Commonly posted woes lamented the long time it takes to travel to and from the west, its lack of attractive amenities, and the dimal number of good food places found there.

Indeed, mention Jurong to most Singaporeans and most stereotypical descriptions tend to emerge, perhaps unjustly so. The west is often characterised by its industrial landscape, and thought to be barren, boring, and even bizarre. After all, those who do not live in Boon Lay may not regard smelling burnt cocoa at the MRT station as an ordinary, everyday experience.

However, Jurong is not as desolate as most people believe it to be. Empty grass fields in Jurong East have now given way to new shopping malls and beautiful landscaping, injecting life into the formerly quiet town. More changes can be expected as plans to develop the Jurong Lake District will commence in the years after 2015. Jurong is on the cusp of another stage of its transformation, perhaps one that will dispel old stereotypes.

A study of Jurong’s past also reveals an intriguing and layered history, of a time when Jurong was home to a number of prawn ponds and well-known for its brickworks. Its successful transformation into a modern industrial estate also tells a tale of unwavering determination and foresight during the period when our nation was only just learning how to stand independently.

The Jurong Heritage Trail, which was launched in April 2015 by the National Heritage Board (NHB), highlights this rich heritage gathered through in-depth research and interviews with residents and workers who once called Jurong their home. The trail shares a colourful history that challenges the notion that the west is without character or heritage. Some sites of heritage still exist today and this article presents a number of locations featured in the trail that people can visit. No passport required.

Imagined Borders and Early Trades

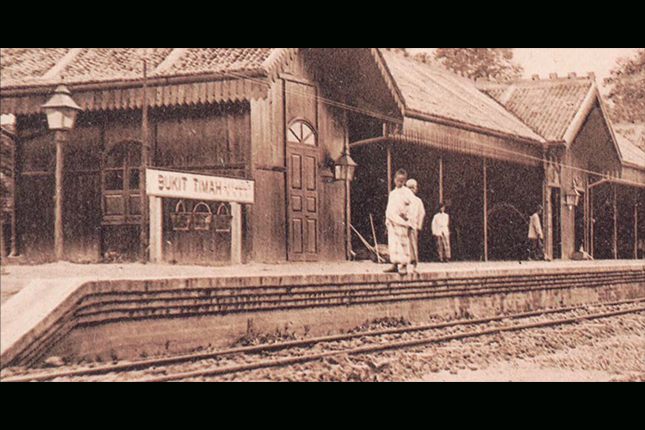

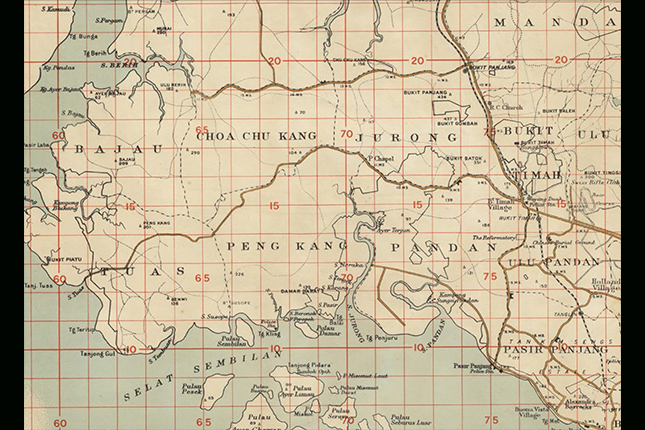

The historical boundary of Jurong as seen on official maps does not quite correspond with the memories of its long-time residents. According to a 1911 map, Jurong was a small parcel of land sandwiched between Choa Chu Kang and Bukit Timah, and was located where Bukit Batok is today. Today’s Jurong East would have been a district called Pandan, whereas Boon Lay was formally called Peng Kang.

Courtesy of Great Britain, War Office, National Library of Australia, G080401936

However, residents like Ng Lee Kar remembered a different Jurong, one whose boundary stretched from the 7 1⁄2 Milestone at Bukit Timah Road to Tuas at the 18th Milestone. This was a large area that spanned the entire length of Jurong Road, once the only road leading to the southwest of Singapore. As many kampongs were only accessible through it, villagers identified their location by the road’s milestones, and hence associated Jurong with the road.

Then, Jurong Road was not like the arterial roads Singaporeans are familiar with today. Consisting of only two lanes, a major accident would have rendered the road completely inaccessible. Former resident Francis Mane summed up this scenario as being “really jialat” (Hokkien term that connotes a difficult situation). His words could certainly be used to describe the day when Nanyang University opened in 1956 near the 14 1⁄2 Milestone. Nanyang University, a national monument, is the first Chinese language university in Southeast Asia and was formed with the help of donations from the local Chinese community. A major traffic jam occurred along Jurong Road on the day of its opening, rendering the motorway impassable, and took the record for the biggest traffic jam Singapore experienced then.

Like many other parts of Singapore, Jurong was covered with plantations, mainly gambier and rubber. But it was the prawn ponds that still evoke fond memories among residents, some whom used to make a living from it. Jurong contained nearly half of the 1,000 acres of prawn ponds in Singapore in 1955. The area where Pandan Reservoir is today used to be covered with mangroves and was a prawn pond reserve. Chua Kim Shua remembered selling these prawns for 40 to 50 cents per kilogram at the market. “I was able to earn about a few hundred dollars a month just selling prawns,” he recalled. “We scooped up the prawns using a pail, and there were many of them then.”

Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

Another notable trade in Jurong was its brickworks industry, a prelude to Jurong’s industrialisation. Jurong was well-known for its brickworks since the 1920s, and once produced as many as three million bricks a month to meet demand in the construction sector in the 1970s. Also, the soil found in Jurong proved to be highly suitable for pottery making; Jurong had an abundance of the sticky mud known as nian tu, which was essential in pottery. This resulted in a burgeoning industry of brick and pottery making.

Today, people can still travel along a remaining stretch of the old Jurong Road entering from Bukit Batok Road or Jurong West Avenue 2. Although the Pandan Reservoir is no longer a prawn reserve, a slice of mangroves at the mouth of Sungei Pandan can still be seen. The reservoir is now an arena for water sports. A legacy of Jurong’s former brickworks industry remains in the form of the Thow Kwang Dragon Kiln and the Guan Huat Dragon Kiln (today’s Jalan Bahar Clay Studio), both located at Lorong Tawas where visitors can also pick up some ornamental pottery.

The Industrial Story

Most Singaporeans would not find the story of Jurong Industrial Estate unfamiliar. Often weaved into the Singapore Story as an example of how the country adapted to remain economically resilient, Jurong’s industrialisation shaped the lives of many individuals who found work in its factories and a new home to live in.

The vast amount of land and its deep coastal harbour made Jurong the ideal location to become Singapore’s primary industrial centre. The first bulldozer entered Jurong in September 1961, and its landscape has been altered permanently since. In spite of the government’s high expectations, only around 24 factories were set up by 1963 — Singapore was far from solving her problems of growing unemployment and declining entrepot trade. It was only through supplying tax incentives, establishing good labour relations, and creating a sense of security for investors did factories finally sprout. By 1970, Jurong boasted 264 factories with 32,000 workers.

Formerly under the purview of the Economic Development Board (EDB), the management of Jurong Industrial Estate was handed over to a new statutory board, Jurong Town Corporation (JTC), in 1968. A new headquarters was built for JTC: Jurong Town Hall. The five-storey building cuts an impressive presence, reflecting a Brutalist style of architecture that emphasises the imposing bulkiness of the concrete structure. The building’s design was from a winning entry of an architectural design competition by a local firm, Architects Team 3, and it was most recently gazetted a national monument for its significance as a symbol of Singapore’s economic progress.

Courtesy of JTC Corporation

The memories of those who worked in Jurong reveal the unique challenges of working in the estate in its early years. Distance was a big issue for those who did not live in Jurong, particularly because of limited public transport services in the area. Woo Lee Tuan remembered the difficulty of getting to work: “Back then, there [was] still no road leading to the estate, and we had to go via Pasir Panjang Road or Jalan Jurong Kechil.” This resulted in many workers sharing rides on pirate taxis, which Woo used to get to work. “The vehicles were actually meant for transporting vegetables and other produce. It was quite an uncomfortable ride.”

Others whose companies provided free transport regarded themselves lucky. As Haji Saleh bin Abdul Wahab recalled, “The company provided private buses from the 7th Milestone. [They] provided transport for you even if you lived very far away like in Geylang.” Food centres were also scarce. Lim Sak Lan, who worked in JTC in the late 1960s shared: “When we were at worksites, we made do with site canteens. There were places away from the sites, but they were shabby little coffee shops and restaurants.”

Despite such discomforts, many of them nevertheless took pride in their work and over time, formed close friendships with their colleagues. Karen Lee, who worked in a spinning mill, reminisced fondly: “When we worked the night shift we would go to the hawker centre to buy food we liked and bring it [back] to the factories for our working colleagues. When we stayed in the company hostel, we were very close... I can [still] remember these people now, even those who came from Malaysia.”

In the present day, Jurong Town Hall still stands along Jurong Town Hall Road. In 2000, JTC moved across the road into a larger building, and the Town Hall is now a space for start-up companies. You can also take a stroll in the Garden of Fame next to the building, which commemorates the visits of many dignitaries to Jurong’s Industrial Estate over the years.

Green Lungs

In the process of conceiving the industrial estate, urban planners wanted to ensure that green spaces were integrated to preserve the beauty of Jurong’s natural landscape. Jurong was meant to be a self-contained garden industrial estate, and thus 12 percent of the land was set aside for public parks, gardens, and open spaces.

The Jurong Lake area is one such green lung planned to separate the industrial from the residential. The lake was formed after the Jurong River was dammed in 1971, creating the 81-hectare freshwater reservoir. Three islands were shaped, housing the Chinese Garden, Japanese Garden, and the golf course of the Jurong Country Club. When it first opened, the Chinese Garden and Japanese Garden attracted immense attention, the former receiving half a million visitors within eight months of its opening in April 1975.

Jurong Hill is another point of attraction. Formerly called Bukit Peropok, the hill is the tallest peak in Jurong today. It was converted into a park in 1968, and a Lookout Tower was constructed at the top of the hill. Residents might remember dining at the Japanese teppanyaki restaurant when it opened in 1970, or spending a leisurely day with the family exploring the hill’s Garden of Fame. The tower offers visitors a sweeping view of the industrial estate, and was a stop point for many visiting heads of states.

Today, the Chinese Garden and Japanese Garden are open for public visits. Jurong Hill is also accessible, although the restaurant has since closed.

To find out more about Jurong’s history, visit the Jurong Heritage Trail.