Text by Tan Huism

MuseSG Volume 8 Issue 1 – Apr to Jun 2015

Maps are fascinating objects. Visual and textual, they tell us about the world they depict and provide a glimpse into the worldview of their makers. In Singapore, maps are especially significant as they are the earliest material evidence of our past.

As part of Geo|Graphic: Celebrating Maps and their Stories, exhibitions and programmes were organized by the National Library that explored maps and mapping in both historical and contemporary contexts. They ran until 19 July 2015.

The two historical exhibitions — Land of Gold and Spices: Early Maps of Southeast Asia and Singapore, and Island of Stories: Singapore Maps — showcase the collections of the National Library and the National Archives of Singapore respectively. They provide amazing insight into the history and transformation of Singapore’s landscape, and how Southeast Asia was imagined and mapped by the Europeans.

Geo|Graphic’s contemporary art components, Mind the Gap: Mapping the Other, and SEA STATE 8 seabook: An Art Project by Charles Lim (co-organised with the NUS Museum), invited visitors to reflect on the concepts of mapping and what maps might look like in the hands of an artist.

Here are some highlights from the exhibitions Land of Gold and Spices and Island of Stories.

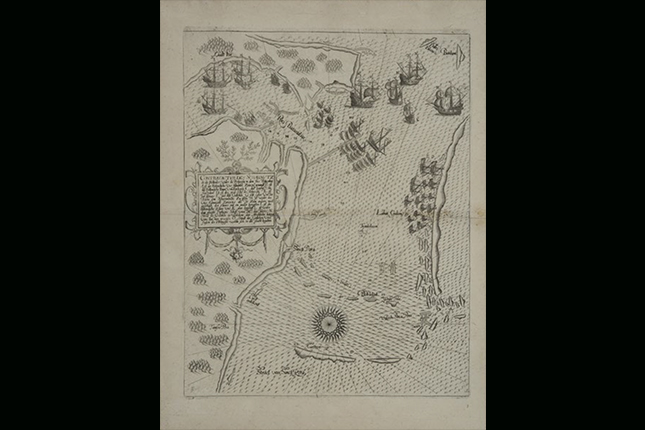

Printed in 1607, this is a schematic map of a brutal Luso-Dutch naval confrontation that took place between 6 and 11 October 1603, in the Johor River (Rio Batusabar) and close to Pedra Branca (Pedro Blanca). The Johor Fleet (allies of the Dutch) is shown waiting at a shoal off the eastern coast of Singapore. The map, produced by Flemish goldsmith, engraver and publisher Theodore de Bry (1528–98), has been drawn with the east orientated to the top.

One of the earliest representations of Singapore’s coastline, the map is also significant for depicting the battle that illustrates the strategic importance of the Singapore Strait as a waterway connecting the Indian ocean to the South China Sea.

This hand-drawn chart that shows the Straat Sincapura (Strait of Singapore) is a V.O.C. (Dutch East India Company)-based chart and might have been derived from an earlier version. The outline of the Long Island (‘t Lang Eylant) referring to Singapore is not completed at the northern part, perhaps reflecting the cartographer’s lack of knowledge of the area. To the south of the strait, a large landmass can be seen. It has a phrase stating that to the southern side of the Singapore Strait are broken islands, or gebrooken eilanden. The cartographer has not drawn the outline of the numerous islands, as little is known about them. This chart with soundings and compass-rose lines, however, identifies two navigational landmarks in the Singapore Strait: Johor Hill and the twin peaks of Bintan, both of which are highlighted in black ink.

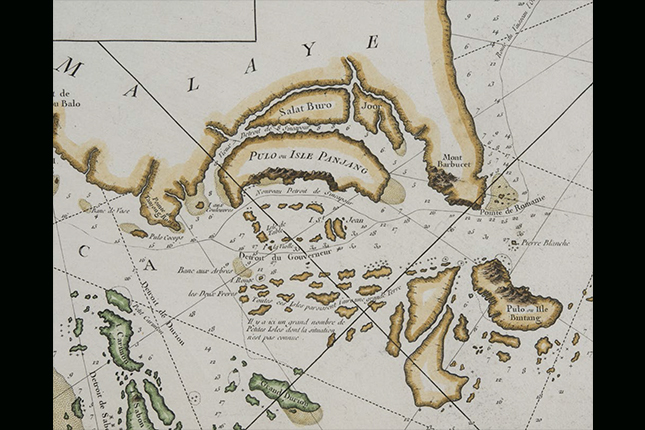

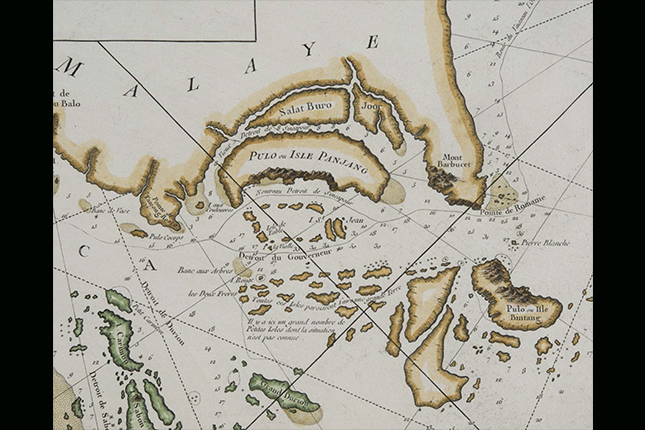

Jacques Nicolas Bellin (1703–72) was a French hydrographer who created maps for several key publications in the 18th century. On this map, Bellin depicts the island of Singapore and calls it Pulo or Isle Panjang (Pulau Panjang, meaning Long Island in Malay, or Panjang Island). If the main island of Singapore is named at all on early European maps, it is most often called Pulau Panjang. On this map, the old Strait of Singapore (Vieux Detroit de Sincapour) is shown as the waterway between Singapore and Johor, which is known today as the Johor or Tebrau Strait (Selat Tebrau in Malay).

Interestingly, Bellin shows two islands on the Johor Strait: Salat Buro and Joor. It seems that Salat Buro, or Selat Tebrau, has been mistakenly depicted as an island; similarly, Joor is presumed to be Johor Lama. The two islands depicted are likely to be present-day Pulau Ubin and Pulau Tekong. The lack of knowledge on most European maps about the Johor Strait suggests that European navigators did not use this maritime route much.

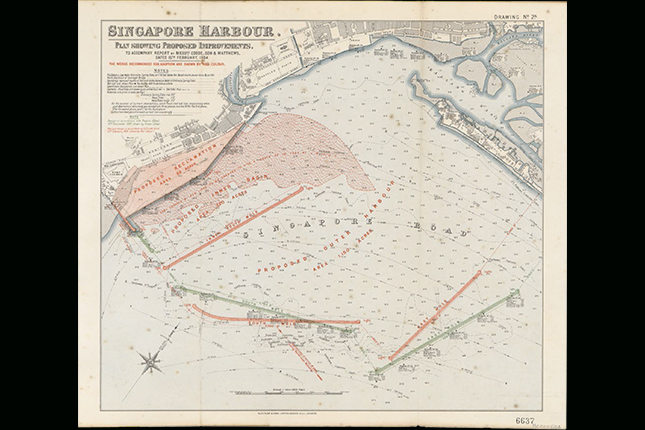

By the early 20th century, Singapore, dubbed the “Gateway to the East”, had become a major international port serving the thriving trade between Asia and Europe. The sheer volume of ships and cargo that Singapore handled strained its port’s infrastructure, which had become inadequate to meet its growing requirements by the late 19th century. This necessitated major harbour improvements, and this map of the Singapore harbour shows the proposed harbour improvement works drawn up in 1904 by the British government’s consulting engineer Coode, Son & Matthews. It contains hydrographic details, including the soundings of the harbour, and the direction and velocity of the harbour’s tides.

Some of the proposed improvements included plans to reclaim land to extend and straighten the wharf at Telok Ayer to make it easier and safer for ships to dock; to deepen the harbour; and to construct a series of moles, or breakwaters. But due to budget and technical difficulties, and public outcry against the move, only the southern inner mole was built. The one-mile-long (about 1.6 km) detached breakwater would remain a major landmark in Singapore until the late 1970s, when the waters around and behind the breakwater were reclaimed to create Marina Bay.

The Imperial Japanese Army reprinted copies of the British Survey Department maps, and this particular reprint of the Singapore Gazetteer Map shows the main roads in the town area of Singapore renamed in Japanese script.

While most of the road names remained unchanged and were simply spelt out phonetically in the Japanese katakana script, public buildings, such as government buildings, hospitals and even cinemas, were given new Japanese names. For instance, Capitol Cinema, Cathay Cinema and Raffles Hotel were renamed Kyo-Ei Gekijo (共榮), Dai To’a Gekijo (大東亜劇場) and Shonan Ryokan (昭南旅館), respectively. The selective renaming of such public landmarks allowed the Japanese administration to assert sovereignty over Syonan-to — Singapore’s name during the Occupation — without causing widespread confusion.

Tan Huism is Head, Exhibitions and Curation with the National Library, Singapore.