Text by Chung Sang Hong

MuseSG Volume 9 Issue 1 - Jan to Mar 2016

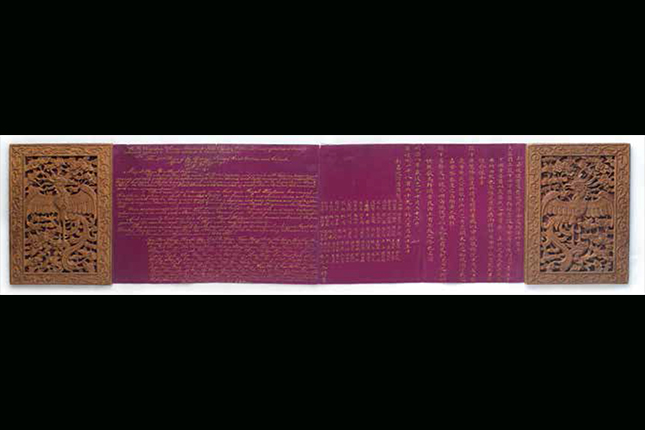

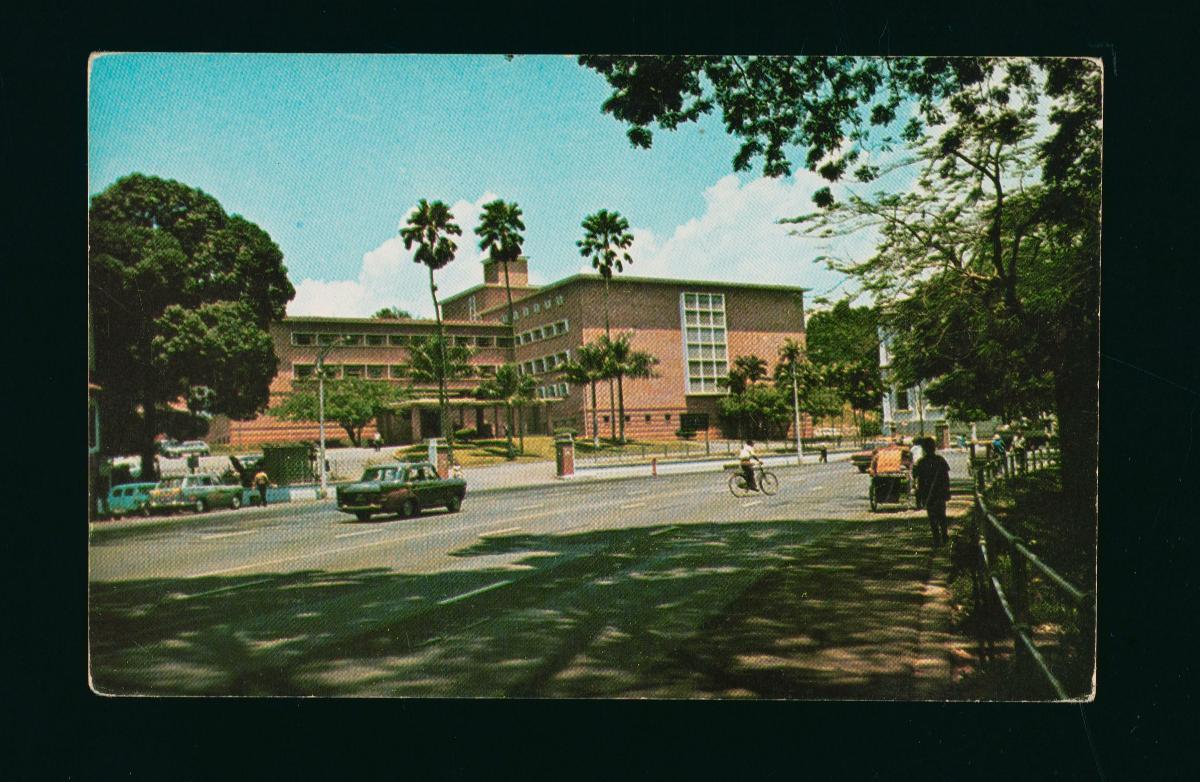

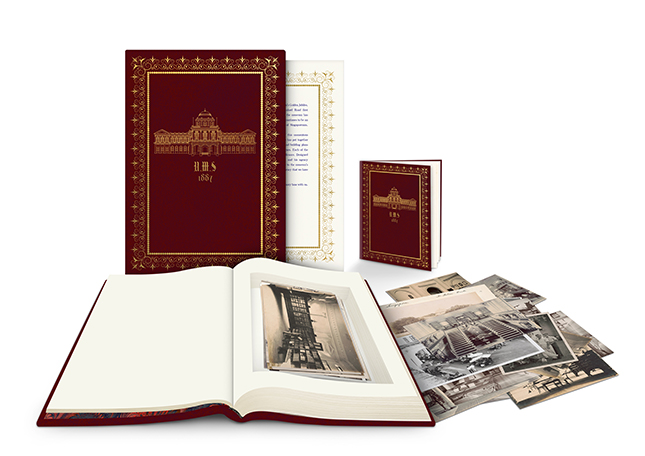

Singapore has inherited a rich published heritage thanks to its history, socio-political development and strategic location at the confluence of civilisations. It was once the publishing hub in the region and a body of printed works, manuscripts and records of every description have survived through the ages. Part of this fascinating legacy was showcased in an exhibition by the National Library of Singapore, From the Stacks: Highlights of the National Library – which took place from January 30 to August 28, 2016 at the National Library Gallery. The exhibition presented over 100 items drawn largely from the library's Rare Materials Collection: Publications, manuscripts, maps, documents and photographs from the 1701 to 1960. Here are some of the highlights.

THE PRIVATE RAFFLES

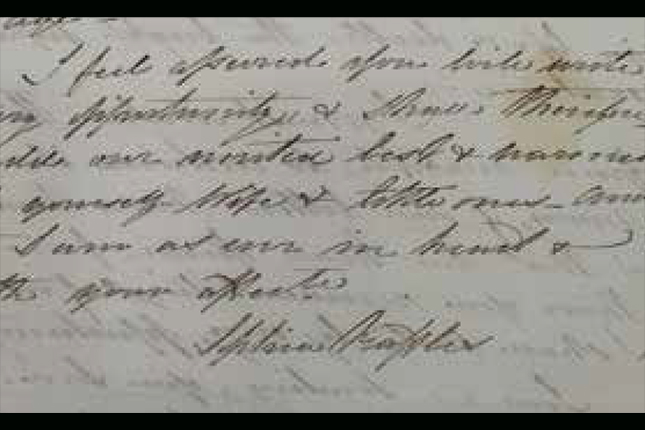

Over the years, the Library has acquired a small collection of holograph letters by Stamford Raffles (1781 to 1826) and individuals related to him, which form an invaluable primary resource material for research on Singapore’s early history and its modern founder. While most of the letters in the collection contain information relating to Raffles’ public life and endeavours, two letters featured in the exhibition provided glimpses into his private life and character.

A letter to his cousin (with the same name) is the longest private and only autobiographical letter by Raffles. It contains a detailed account of his career progression as well as reminiscences of his humble early life. Due to family circumstances, Raffles withdrew from school when he was barely 14 and worked as a clerk with the East India Company. Despite the hardship, he persevered in self- study and mastered French and acquired knowledge in literature and science. On his learning and family poverty he recalled:

“This was, however, in stolen moments, either before the office hours in the morning, or after them in the evening; and I shall never forget the mortification I felt when the penury of my family once induced my mother to complain of my extravagance in burning a candle in my room. And yet I look back to those days of misery, difficulty, and application with some degree of pleasure. I feel that I did all I could, and I have nothing to reproach myself with.”

The letter to the same cousin by Raffles’ second wife Sophia (1786 to 1858) portrays a blissful scene the Raffles family enjoyed in Bencoolen (present-day Bengkulu), Sumatra, where Stamford Raffles was the Governor-General from 1817 to 1823.

“Our domestic scene is so blessed and happy, I scarcely know how to describe it – my dear husband’s health and spirit are so bright and light and his mind so relieved from anxiety and cheered by the consciousness of having performed his duty, thus the present scene is more than usually happy – my sweet children are expanding daily – my little Lily is so gentle and interesting, that I am sure you would love her and I am as certain that you would love her bolder brother, because he is a miniature picture of his father in form, in face, in manners and I hope hereafter to add in mind, I have been so blessed as a mother. I ought not to regret the expectation of an additional tie next month but I could have been satisfied with the treasures I now possess and in watching them have formed sufficient occupation.”

Unfortunately, such happy scenario was very short-lived as four of their five children did not survive past early childhood and died of illnesses in the next few years before Raffles and his family returned to England in 1824.

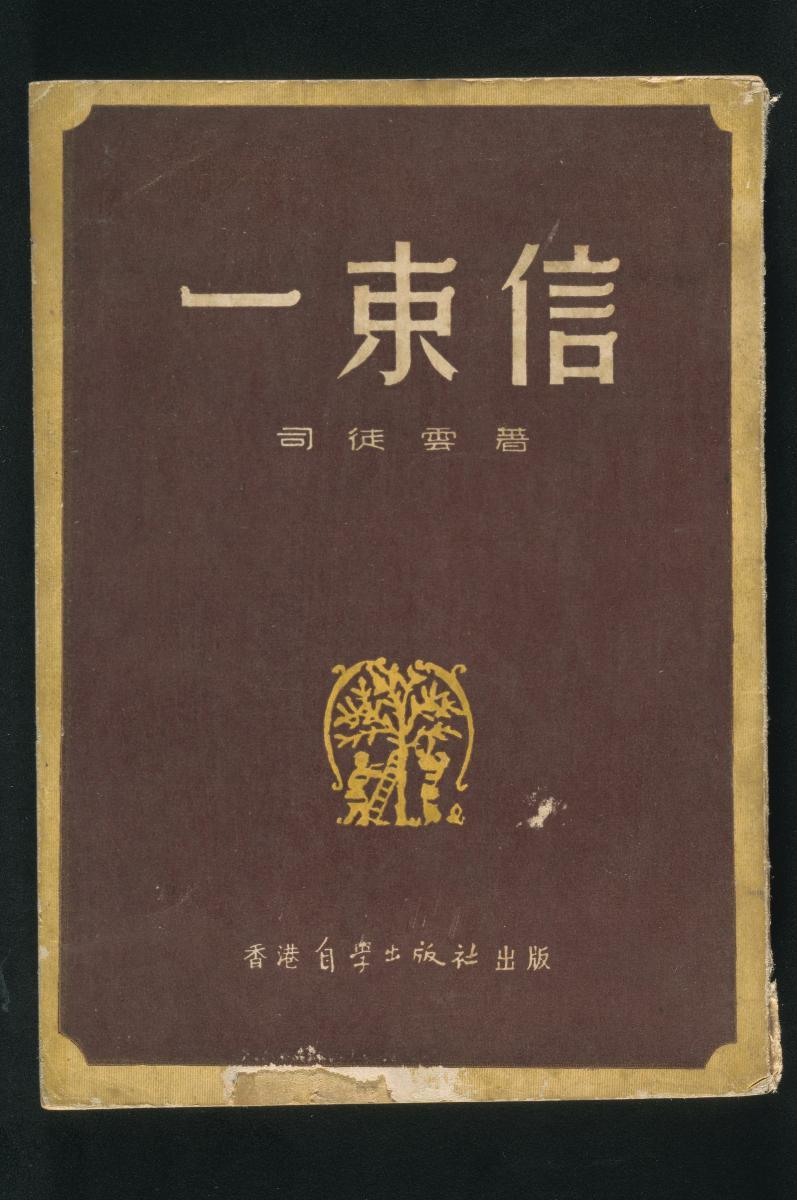

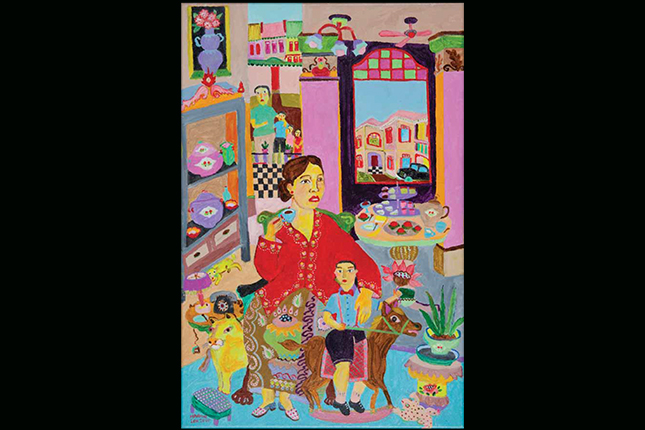

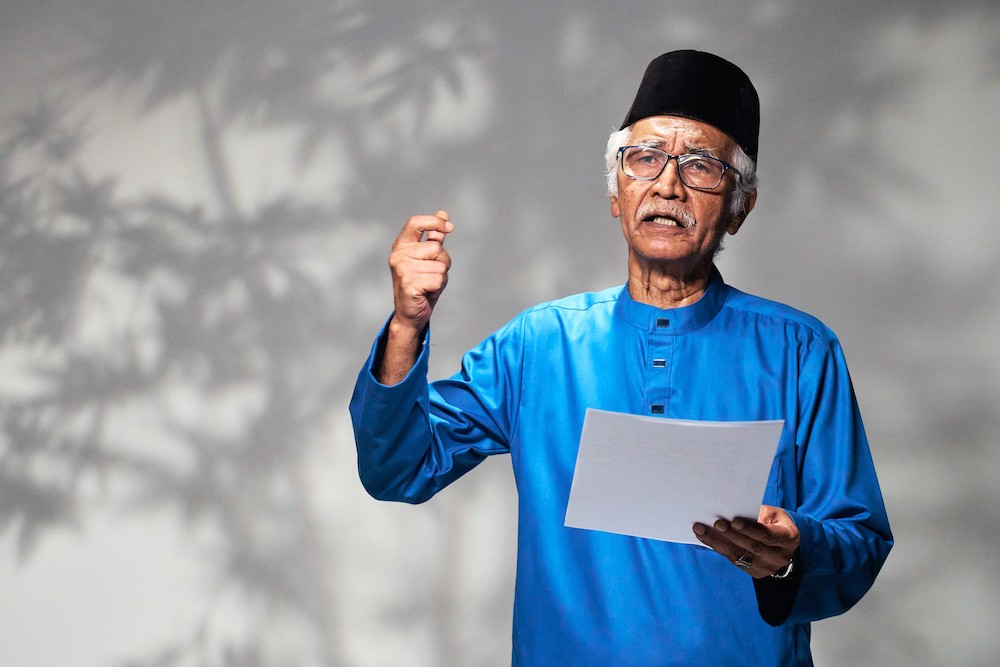

“MALAYANISED” LITERATURE

The Malay language has been the lingua franca of maritime Southeast Asia for centuries. Traders and travellers had to learn Malay in order to communicate with the local populations. For some early diasporic communities such as the Peranakans, they adopted the language and spoke a creolised form of Malay peppered with Hokkien words and phrases known as Baba Malay. It is thus natural to find that some early books published in Singapore were in Malay or about the Malay language. To help with learning of Malay, dictionaries and grammar books were produced. Attempts were even made to teach Malay through nursery rhymes, such as a compilation of English nursery rhymes translated into Malay and adapted to local culture. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Baba Malay translations of Chinese historical novels were very popular among the Peranakan community.

Some examples of 'Malaynised literature' were showcased in the exhibition.

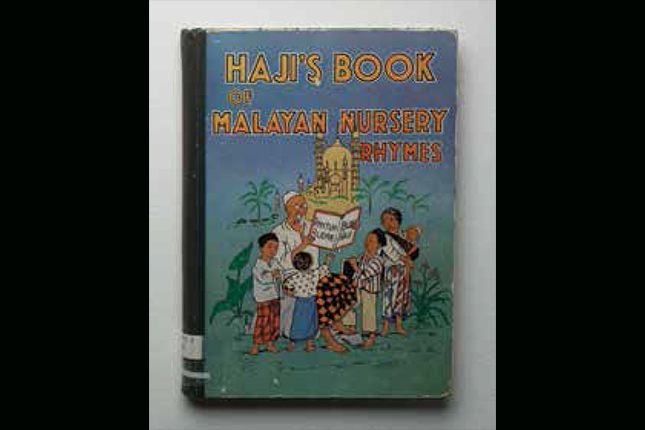

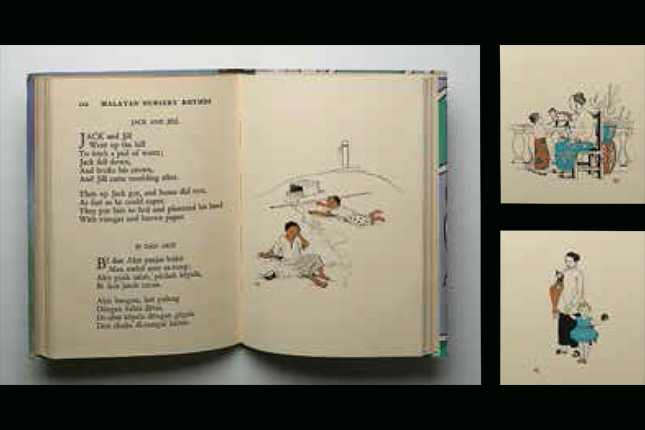

“HAJI’S BOOK OF MALAYAN NURSERY RHYMES”

In this collection of popular nursery rhymes both the original English version and the Malay translations are featured. In the latter, some words were replaced with local terms to give a familiar Malayan setting, for example, “Jack and Jill” became “Bi dan Akit”. The book was intended to be used for learning Malay as it includes a glossary of Malay vocabulary for the benefit of readers not proficient in the language. The book features charming illustrations depicting idyllic Malayan lifestyles in the pre-World War Two era.

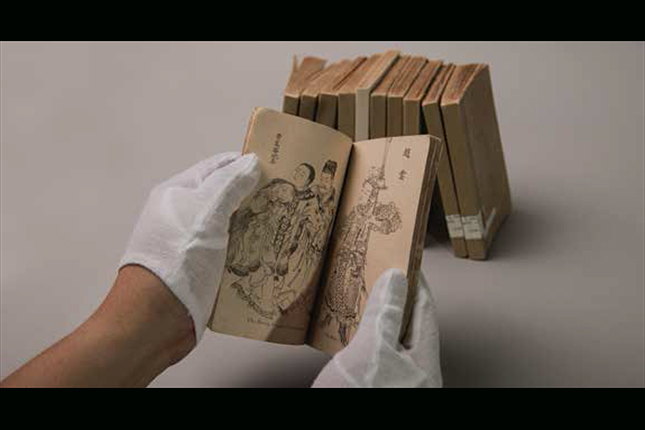

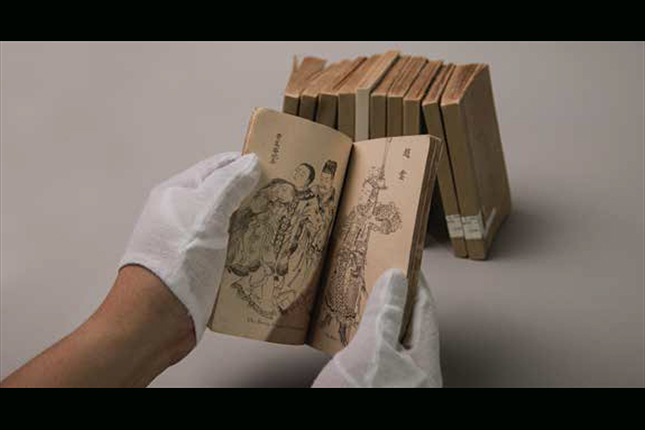

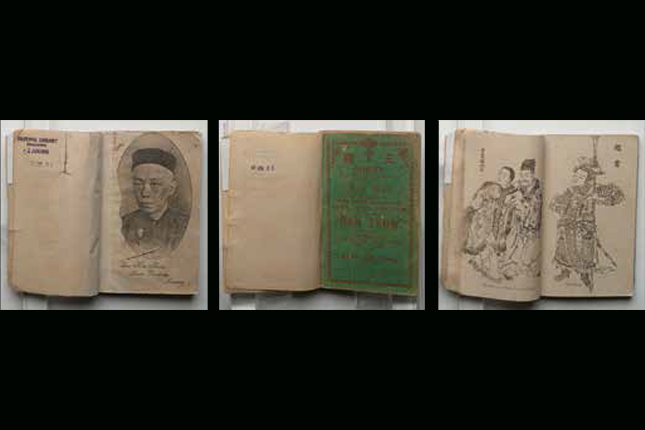

“HANTEOW”

This serialised 30-volume novel is probably the earliest Baba Malay translation of the Chinese classic Romance of the Three Kingdoms. From 1880s to 1942, translations of Chinese historical novels in Baba Malay were highly popular among the upper middle class Peranakans in Java and the Straits Settlements. They were indeed bestsellers of the day with a print run of up to 2,000 for each publication in 1930s.

Among the numerous translators of such novels in Singapore, Chan Kim Boon (1851 to 1920) was the most illustrious. A native of Penang, Chan was educated in English but received private tutoring in Chinese. He pursued further studies at the Foochow Naval School (in present-day Fuzhou) and went on to teach mathematics in that institution. He came to Singapore in 1872 to work as an administrator at law firm Aitken & Rodyk. However, he was better known for his translations of three Chinese classics: Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sam Kok), The Water Margin (Song Kang) and Journey to the West (Kou Chey Tian).

RECIPES FROM THE MELTING POT

Singapore’s melting pot of cultures has produced a rich multi-ethnic culinary heritage with countless recipes passed down through the generations. Certain Singapore published cookbooks were once regarded as “cookery bibles” and presents a myriad of sumptuous Malayan dishes.

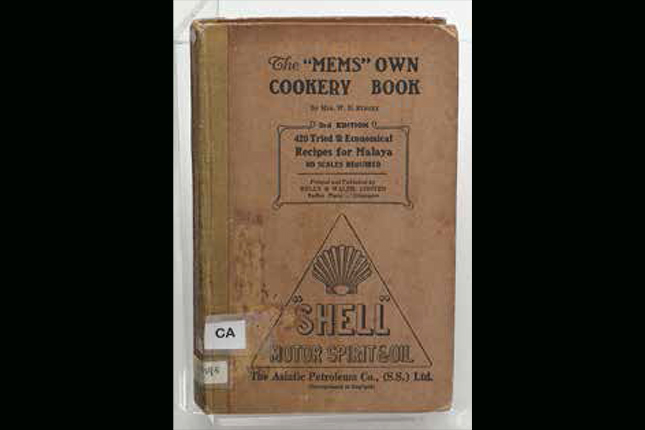

The book contains “tried and tested” recipes which the author compiled while living in Seremban, Malaya between 1915 and 1919. The recipes emphasise on economy due to the shortage of food and price hikes during World War I. It was written for expatriate wives who wished to cook for their households instead of relying on local cooks. When first published in 1920, it sold out in a few months.

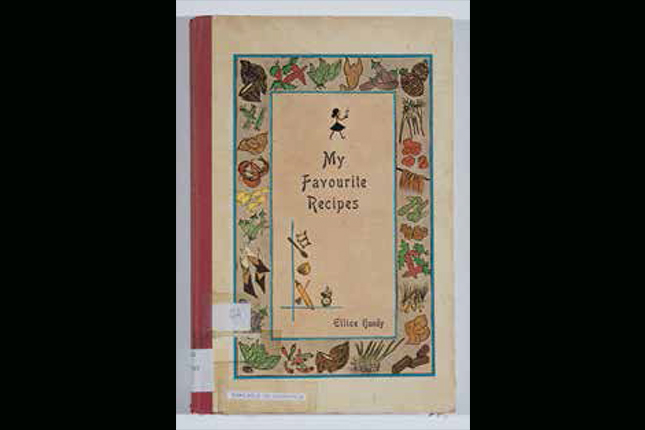

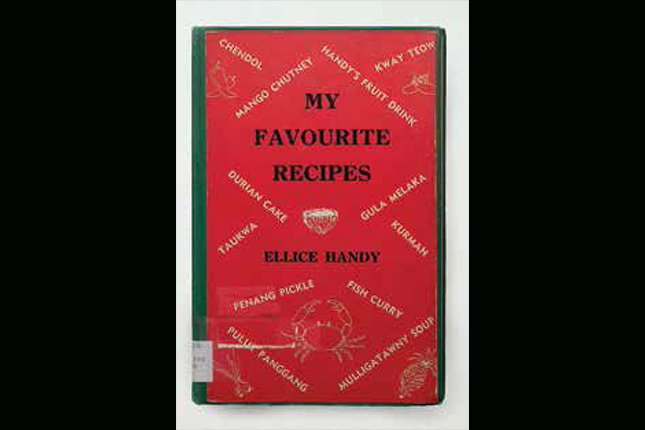

MY FAVOURITE RECIPES

The recipes were meant to create typical European or British fare using local ingredients. Tips on local weight measurements, food prices and names of ingredients in Malay are given. A small proportion of the recipes are on local dishes such as satai (satay), rundang (rendang), curries and gula malacca. Several dishes probably would have been rather exotic to the locals, such as sheep’s brain on toast, sheep’s head broth, and jugged sheep’s heart.

This is the first cookbook by a Singaporean author, Ellice Handy (1902 to 1989), a Eurasian educator. First published in 1952, it contains recipes from the various communities in Malaya and catered to a cosmopolitan audience – the book includes a chapter on “Asian Recipes that can be used in U.K., U.S.A., Australia and places where Malayan Curry Ingredients etc., are not available.”

On creating the Malayan flavour, Mrs Handy offered the following tips:

“If we want a Malayan-style dish of Chinese Beehoon (Rice Noodles) or Nasi Goreng (Fried Rice) we use a paste of pounded fresh red chillies and blachan (shrimp paste) and onions, instead of or in addition to the garlic and onions.”

“To European stews we add cloves and cinnamon and to omelette we add plenty of sliced onions and chillies and just before serving a teaspoon of soy sauce. When we roast a chicken the addition of ground cinnamon, cloves and pepper, thick soy sauce and a little sugar makes it a Chinese style dish, while the addition of the “Satay Paste” gives it the very popular Malay Satay flavour.”

As a culinary classic and the longest selling local cookbook, 11 editions have been printed since 1952 with the most recent one released in 2012.

There were too many publications of note in the exhibition to be highlighted in this article. The exhibits covered a wide array of topics, from politics, history, sociology, language and religion to current affairs, nature, travel, food and more. Some of the more novel items on display included an address to Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh by the Singapore Chinese merchants on the occasion of his visit in 1869; a 1901 photo album by G.R. Lambert with images of old Singapore and what is probably the first travel guidebook of Singapore, published in 1892. Visitors also saw for the first time English-Malay dictionary (1701); early nineteenth century Christian literature published by the Mission Press, the first printing press in Singapore; one of the earliest Qur’ans printed in Singapore (1869); and photographs of the war crime trials held at the Supreme Court in 1946.