The Chinese of early Singapore

The first bulk of arrivals in Singapore were mainly men who took on backbreaking work moving commodities and cargo from sea vessels to warehouses along the Singapore River.1 Known as coolies, these indentured labourers also worked in construction, agriculture, shipping, mining and rickshaw-pulling.2 As the port town of Singapore evolved, it received a regular influx of Chinese male immigrants. By and large, they came in three large waves between 1823 and 1927.

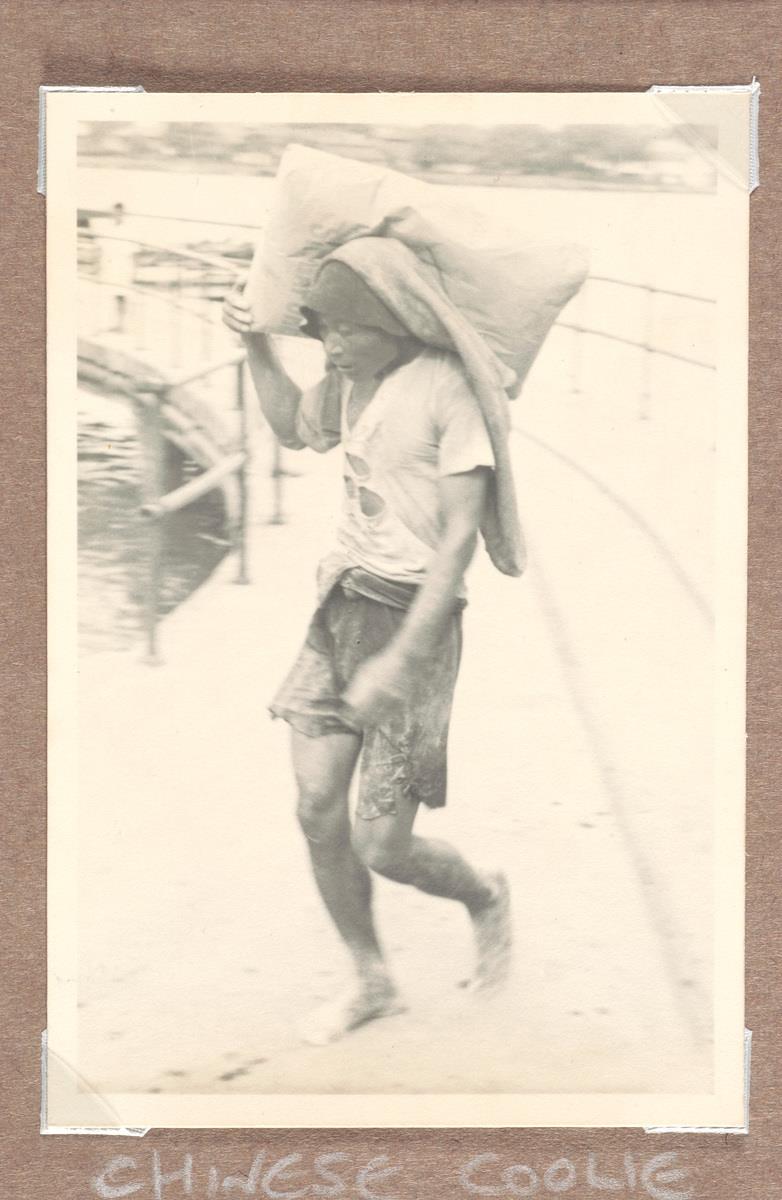

A Chinese coolie, early-mid 20th century. Collection of National Museum of Singapore.

A Chinese coolie, early-mid 20th century. Collection of National Museum of Singapore.

Unfortunately, life was far from rosy. On top of desperately low wages, and miserable living conditions, the majority of them owed money to middle-men from clan associations and secret societies for arranging passage and work in Singapore. Clan associations were far more understanding of their plight, granting them lodging and protection, as well as aid via mutual assistance schemes. However, immigrants who cut deals with secret societies had to pay membership fees to cover costs in the event they fell ill or died here. As a means of escape, many gambled or smoked opium.

Along the way, the authorities in Singapore curbed the number of male immigrants to the colony and relaxed its policies towards female emigration to even out the gender ratio. Between 1934 and 1938, 200,000 women, affected by economic challenges and a slew of natural calamities in China, came to Singapore.

Here, they found work in tin mines and rubber estates. Those who did general labour at construction sites around the island came to be known as samsui women. They primarily hailed from poor regions in China such as the Samsui district. Their work day usually started at 8am and they were largely tasked to dig soil. They carried earth, debris and building materials in buckets hung from shoulder poles. After work, they returned to tiny shared rooms in Chinatown.

Samsui women working at a construction yard, 1938-1938. (Collection of the National Museum of Singapore.)

Samsui women working at a construction yard, 1938-1938. (Collection of the National Museum of Singapore.)

A majie's comb from the mid-20th century. Majies participated in a ceremony where they combed their hair up into buns and took vows of celibacy. (Collection of the National Museum of Singapore)

A majie's comb from the mid-20th century. Majies participated in a ceremony where they combed their hair up into buns and took vows of celibacy. (Collection of the National Museum of Singapore)

Making a Mark

A number of sojourners to Singapore were so successful in their endeavours that their names have been immortalised around the island.

Take the case of Malacca-born vegetable seller turned tycoon, Tan Tock Seng. A hospital which he helped set up in the 1840s was named after him.5 It stands in Novena today.

Tan Tock Seng Hospital, c. 1876. (Collection of the National Museum of Singapore)

Tan Tock Seng Hospital, c. 1876. (Collection of the National Museum of Singapore)

Then there was ship chandler and one-time ice merchant Whampoa Hoo Ah Kay who was not only wealthy, but also an accomplished diplomat. A housing estate in a subzone of Balestier bears his name.6

Meanwhile, Hokkien merchant Chia Ann Siang, who traded in spices, coconut, tobacco, tin, tea and silk, has a hill in Chinatown named after him while Peranakan tycoon Tan Kim Seng who donated generously to water works, was honoured with a fountain at Esplanade Park.

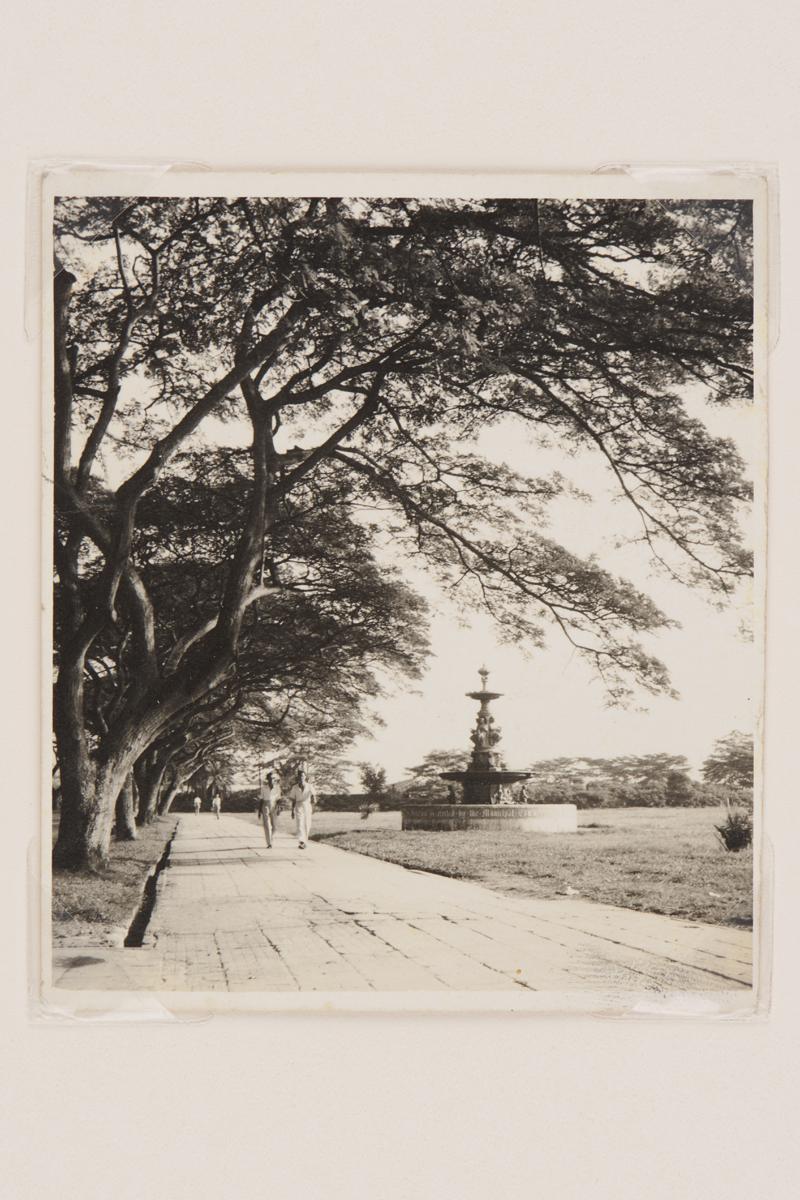

The Tan Kim Seng fountain, 1950s-1960s. (Collection of the National Museum of Singapore)

The Tan Kim Seng fountain, 1950s-1960s. (Collection of the National Museum of Singapore)

Along Orchard Road, Singapore’s premier shopping belt, stands Teochew immigrant C.K. Tang’s department store. He set it up after a decade of peddling Swatow lace and embroidery from a tin trunk.7

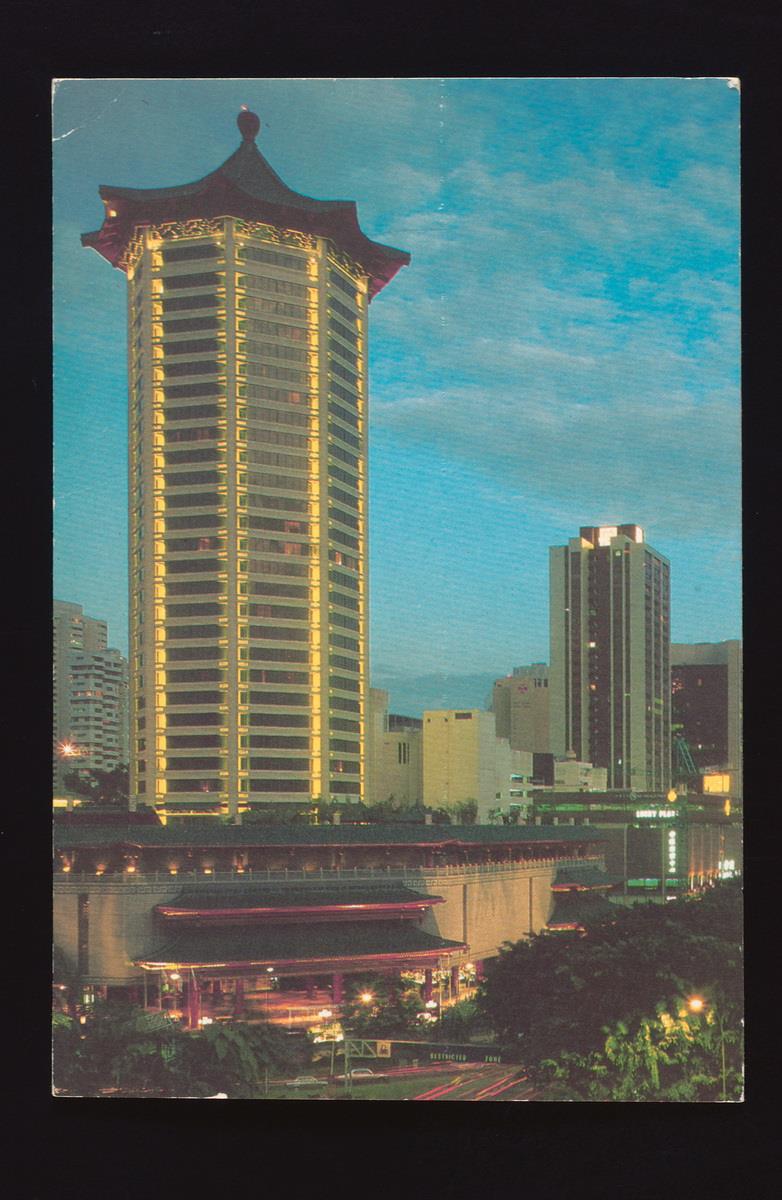

The Dynasty Hotel and Tangs Department Store at Orchard Road, mid-late 1980s. (Collection of the National Museum of Singapore)

The Dynasty Hotel and Tangs Department Store at Orchard Road, mid-late 1980s. (Collection of the National Museum of Singapore)