Situated at the crossroads of the Indian Ocean region and the Far East, the Malay Archipelago has always been a region of cultural confluence and diversity. The region experienced an influx of migrant communities which brought with them their unique socio-cultural traits ranging from language to religion, fashion to cuisine. Over time, these traits adapted to the multicultural milieu of the local society and resulted in polyglot environments best exemplified by the Chetti Melaka.

The Chetti Melaka (or Chitty Melaka) are descendants of Tamil traders who settled in Melaka during the reign of the Melaka Sultanate (15th – 16th centuries) and married local women of Malay and Chinese descent. Predominantly Hindu of the Saivite (followers of Shiva) denomination, the community speaks a unique combination of Malay, Tamil and Chinese, which has been called Chetti Creole by scholars. They trace their roots to Kampung Chetti in Gajah Berang, Melaka, and it is estimated that there are 5000 Chetti Melaka in Singapore.

The Indian Heritage Centre (IHC), in collaboration with the Peranakan Indian (Chitty Melaka) Association Singapore, proudly presents Chetti Melaka of the Straits – Rediscovering Peranakan Indian Communities, the first of IHC's community co-created exhibitions.

Who are the Chetti Melaka?

The story of the Chetti Melaka community is relatively unexplored and waiting to be discovered and documented. Who are the Chetti Melaka? Where are they located? What is their story? Discover the answers to these questions through this introductory film produced by the Indian Heritage Centre.

Shot in Singapore and Melaka in documentary style, this film presents the journey of two Chetti Melaka youth in search of their roots, and unearths lesser known facets of the Chetti Melaka in Singapore. On a quest for their identity, the protagonists re-examine the importance of their heritage as many young Chetti Melaka have lost touch with their root culture.

The film also contemplates the future of Singapore’s relatively unknown Chetti community and documents how the Chetti Melaka are struggling to preserve their identity, heritage and culture. Through the use of oral history interviews, archival photographs and stylised re-enactments, the film provides a succinct overview of Singapore’s contemporary Chetti Melaka community, its history and heritage.

Early Beginnings

Watch: Early Beginnings of the Chetti Melaka

During the 15th century, Malacca (now Melaka) was a bustling entrepôt and attracted traders from across the world. South Indian traders arriving from the Coromandel Coast intermarried with local Malay and Chinese women, and established a Chetti Melaka community that survived the Malacca Sultanate and centuries of Portuguese, Dutch and British rule.

While these traders gradually absorbed local influences including Straits language, food and dress, they continued to adhere to their root religious practices. Over time, the descendants of such locally-settled traders from the Coromandel Coast came to be known as the Melaka-born Hindus or Chetti Melaka. Due to assistance rendered to them at the time of the conquest of Malacca, the Portuguese favoured the Chetti Melaka.

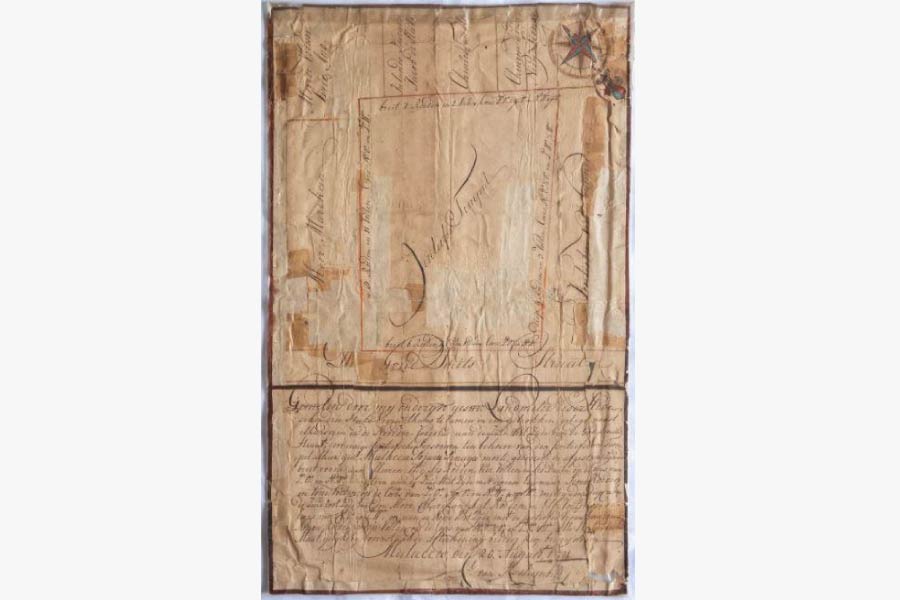

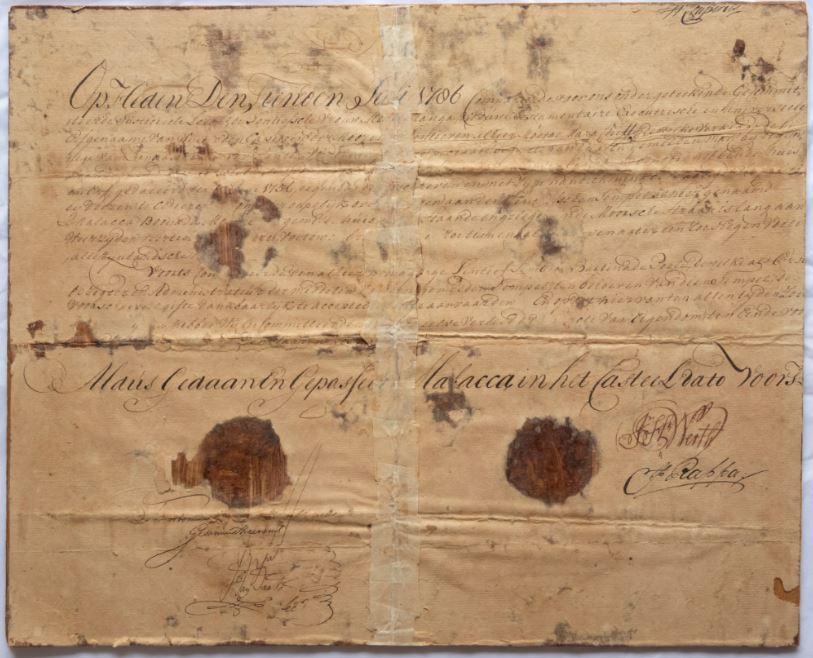

However, the fall of Melaka to the Dutch in 1641 and the ensuing Dutch trade monopoly forced the Chetti community to take up other occupations. The Dutch granted agricultural land to the influential Chetti community in the late 18th century outside the city walls. Over time, the area including Gajah Berang in Melaka became a designated village for the Chetti Melaka.

The 18th and 19th centuries marked a significant decline in the prosperity of the community. With the arrival of the British in 1795, the community found employment in the civil service, especially in Kuala Lumpur, Singapore and other emergent towns outside Melaka.

Kampung Chetti: Roots in Melaka

Watch: Kampung Chetti: Roots in Melaka

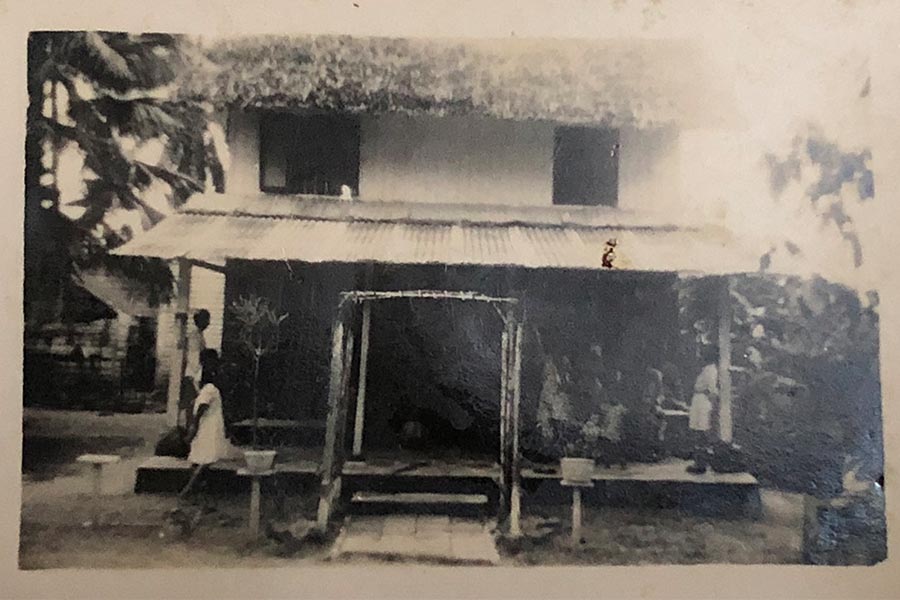

For the Chetti Melaka, Gajah Berang is the only known home town since most Chettis are unaware of the places of origin of their forefathers in India. The majority of the Chetti families live in Land Lots 28, 94, 118 and 138, in clusters around Gajah Berang, Bachang and Tranquerah which constitute Kampung Chetti. This clustering of the community in Kampung Chetti has resulted in the preservation of the community’s distinct lifestyle and cultural heritage.

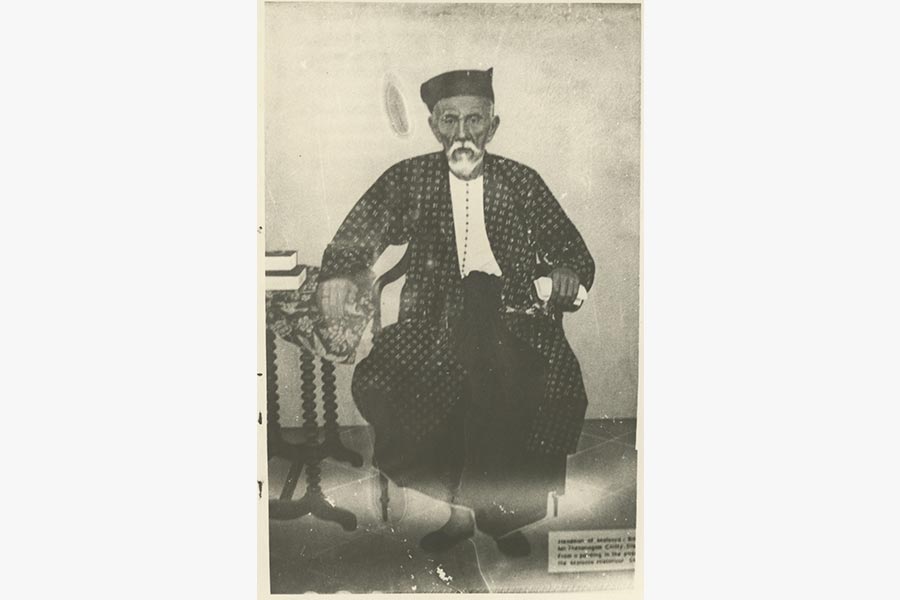

The community’s affairs and temple properties are managed by the community’s headman in the style of the Indian panchayat (Hindi: village council) system. In accordance to Hindu practice where devotees donate properties to the service of the deity, a number of Chetti Melaka have donated lands to the Sri Poyatha Vinayagar Moorthi Temple Trust.

By the 1980s, scholars estimated that there were around 400 families living in Melaka. Since then, the size of the community has dwindled considerably and Melaka is home to fewer than fifty Chetti Melaka families today. However, Chetti families from Singapore and Kuala Lumpur, who are now second or third-generation diaspora, still visit the kampung regularly, and in doing so, maintain their connections with their hometown.

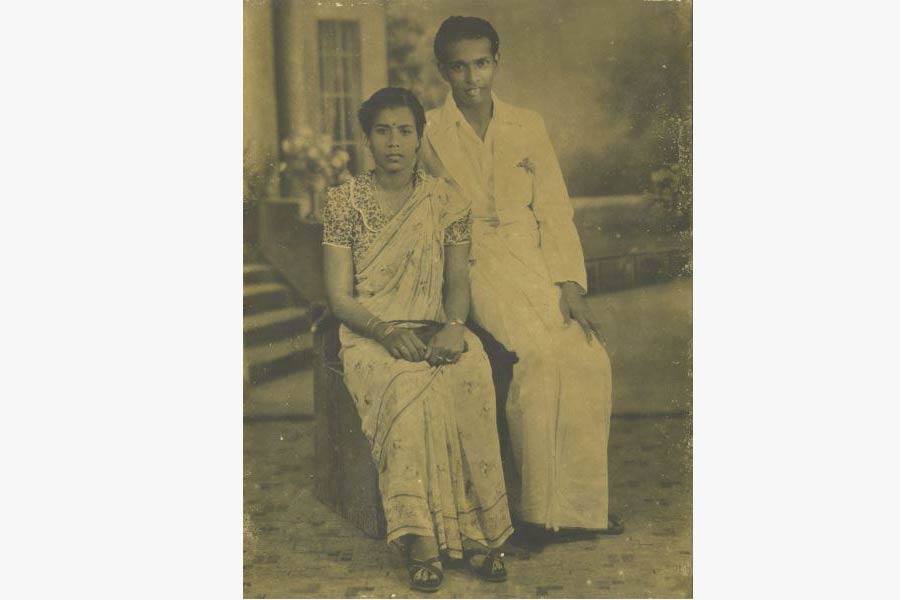

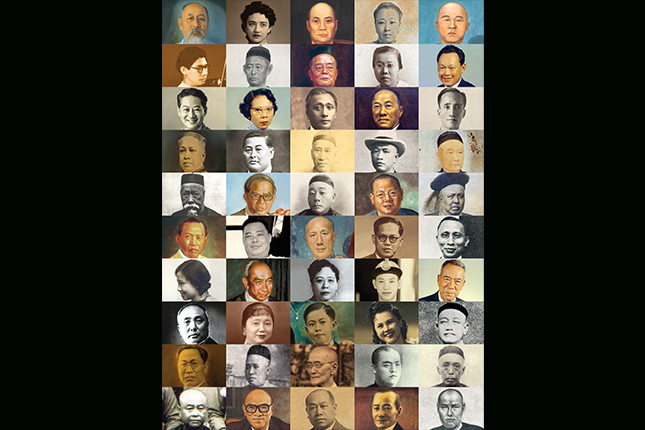

Our Chetti Melaka Pioneers

Watch: Our Chetti Melaka Pioneers

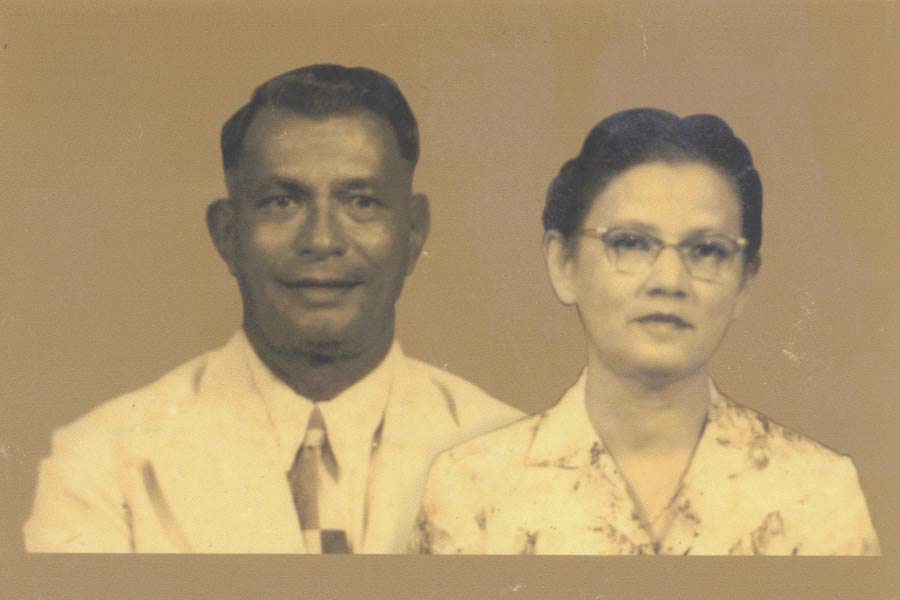

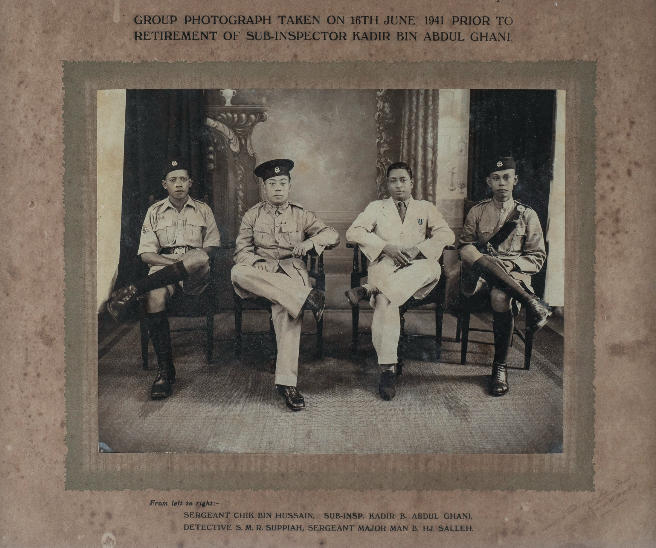

By the time of the British occupation of Melaka, the port city was significantly diminished in importance. Conversely, by the early 20th century, Singapore had started to flourish as a cosmopolitan city and became a popular destination for Chetti Melaka migrants leaving Melaka. During this period, Singapore was under British rule and employment in the British civil service presented Chetti Melaka with opportunities for further education and economic advancement.

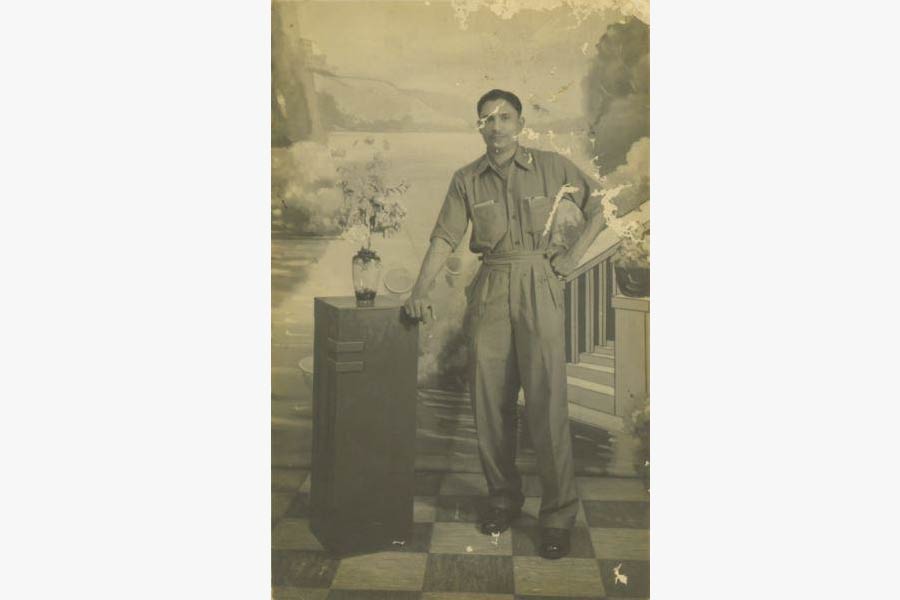

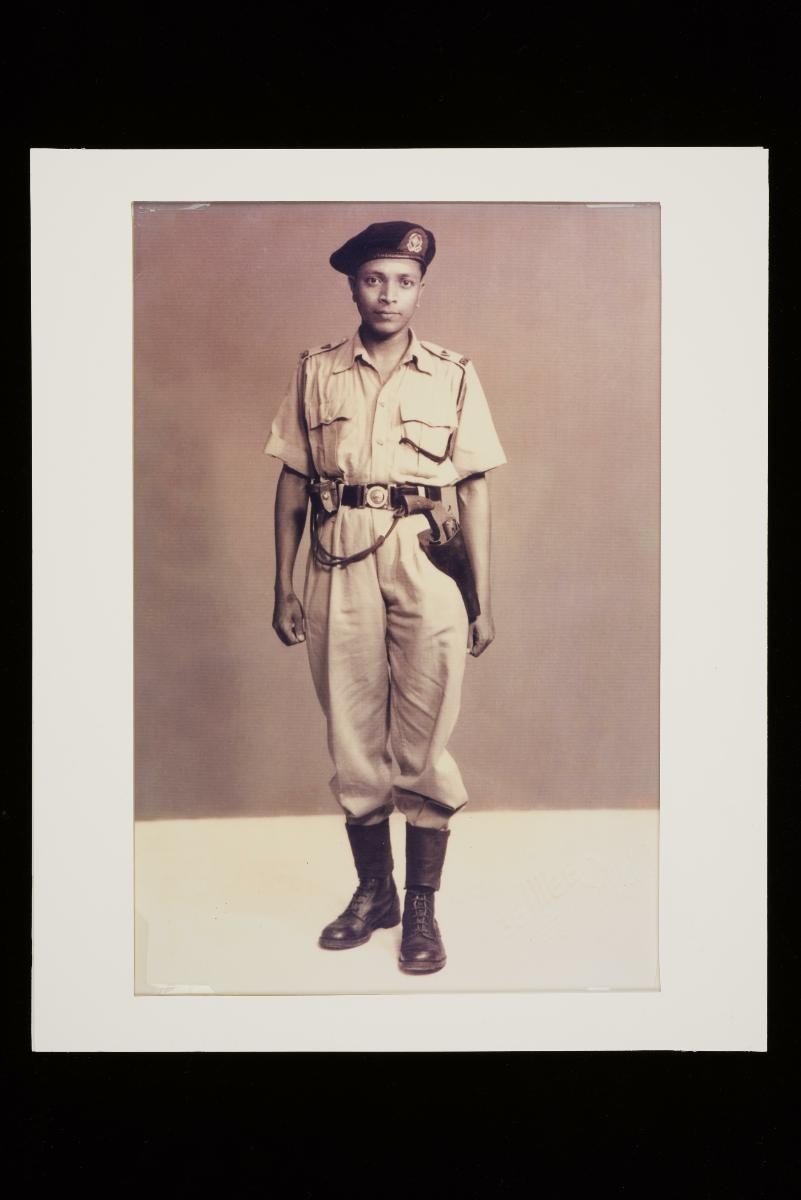

The migration of many young Chetti Melaka from Melaka to Singapore was further fuelled by the ease of travel and access to education, and they often found employment as accountants, clerks and administrative staff in the colonial service. Many Chetti Melaka also joined the police forces and held high ranking positions.

These early waves of migration were also made possible by pioneers such as Muthukrishnan Tevanathan Pillay, Arumugam Supramaniam Chitty and Arunasalam Sithambaram Pillay. After arriving in Singapore before World War II, these early migrants held influential posts and played a key role in facilitating the movement of other young aspirants who were seeking opportunities outside Melaka. It is believed that about 50 per cent of the Chetti community in Melaka migrated to Singapore to take up employment in the private sector or in the colonial government service.

Many of the early Chetti Melaka in Singapore became lawyers, teachers, government clerks, military, and/or police personnel. They included Mr Sandy Gurunathan Pillay, a successful lawyer and advocate as well as the President of the Indo-Malayan Association; and Mr Apoo Pillay (or Dollah as he was known), brother-in-law of Mr Pillay, who was employed in a legal firm.

Other early Chetti pioneers included Mr Ramasamy Suppiah Naidu who migrated from Melaka to Singapore around 1920 and joined the police force; and Mr Francis J Pillay who fought in defence of Singapore during World War II. After the war, Mr Pillay was transferred to the Executive Service in Singapore and later had an illustrious career in the Marine Department and Education Ministry.

Makan Chetti

Watch: Makan Chetti

Chetti Melaka cuisine is a fascinating blend of Indian, Malay and Nonya (Peranakan Chinese) culinary styles and offers a wide variety of delicacies for every occasion. For Chetti Melaka cuisine, traditional Indian spices are typically combined with Malay ingredients such as belacan (shrimp paste), serai (lemongrass), lengkuas (wild ginger), pandan leaf and coconut milk to create uniquely Chetti dishes.

Traditional Chetti Melaka favourites include ikan parang (fish curry), lauk pindang (fish in a tamarind curry), ikan sipat masek nanas (fish in a pineapple curry), and sambal belimbing (pickled sour fruit). The curry dishes are typically accompanied by rice dishes like nasi lemak (fragrant rice dish) prepared in a uniquely Chetti manner using cooled steamed rice boiled with coconut milk and pandan leaves.

For the Chetti Melaka, festivals and special occasions are marked by the preparation of specific dishes. For instance, Chetti Melaka prepare nasi lemak for prayer offerings and nasi kembuli (rice cooked with cashew nuts and spices) for new brides. Puttu, a traditional south Indian dish is served during the puberty ceremony while dosai (rice flour pancake) and fish curry, are associated with Deepavali.

As with many communities, food remains a central part of Chetti identity and brings the young and old together. For the Chetti Melaka, special occasions are marked by an abundance of sweets and cakes. These cakes are usually prepared using a combination of coconut, palm sugar and flour based on Malay recipes. Some popular Chetti Melaka cakes and desserts include pulot tekan, kwey wajek, kwey ondei ondei, kwey kanda kasturi, and penggat durian.

Chetti Creole

The mother tongue of the Chetti community is a Malay-based creole which reflects the diverse roots of the community. Termed Chetti Creole by researchers JA Grimes in 1996 and Noriah Mohamed in 2009, it is a rare mixture of the predominant languages of the Straits comprising Bazaar Malay, Tamil and Chinese. For instance, the terms for grandmother are nenek (Malay), grandfather thatha (Tamil) and uncle mama (Tamil) respectively.

Chetti Creole shares similarities with several Malay dialects and creole languages spoken in Singapore and Malaysia, including the Baba Nyonya Malay creole language of the Peranakan Chinese, the Melayu Ambon creole language and the Jakarta Malay creole language (Betawi Malay). It is also similar to the creole language spoken by Sri Lankan Malays.

The Malay language plays a key role in Chetti Creole and this is evident in the fact that the Chetti Melaka still pray in Malay while retaining some common Sanskrit and Tamil religious terms used by the Hindu Chetti. Besides the use of Malay terms and phrases, the Chetti Melaka are also fluent in English due to British influence. English is also used as a common medium of communication for day-to-day interactions with other ethnic groups as well as by Chetti Melaka who have married outside the community.

| Chetti Creole | English |

| Ijo | green |

| Mangkok | cup |

| Kalo | if |

| Pande | smart |

| Nyari | today |

| Napas | breath |

| Lu orang | everybody |

| Bikin apa | What to do |

Watch: Chetti Creole

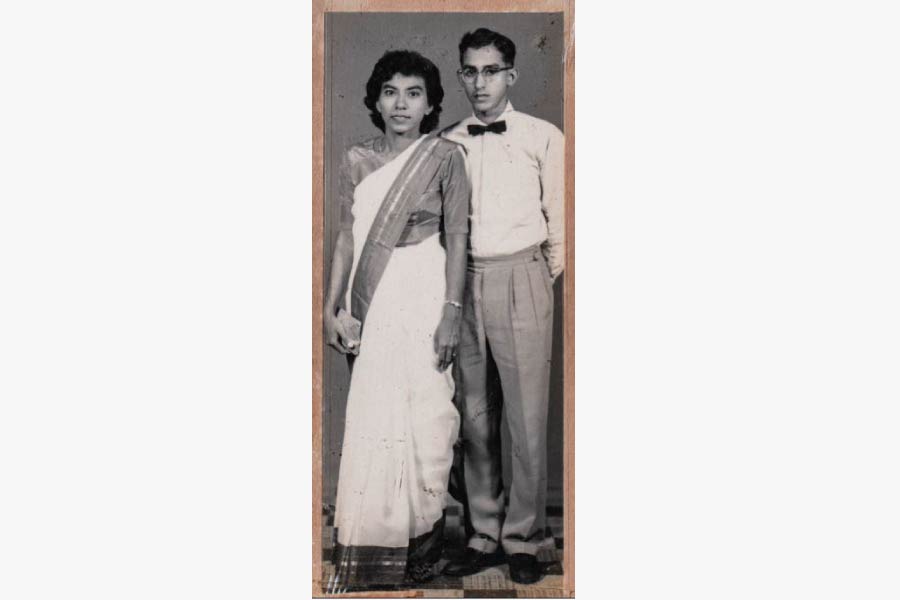

Fashion

Watch: Fashion

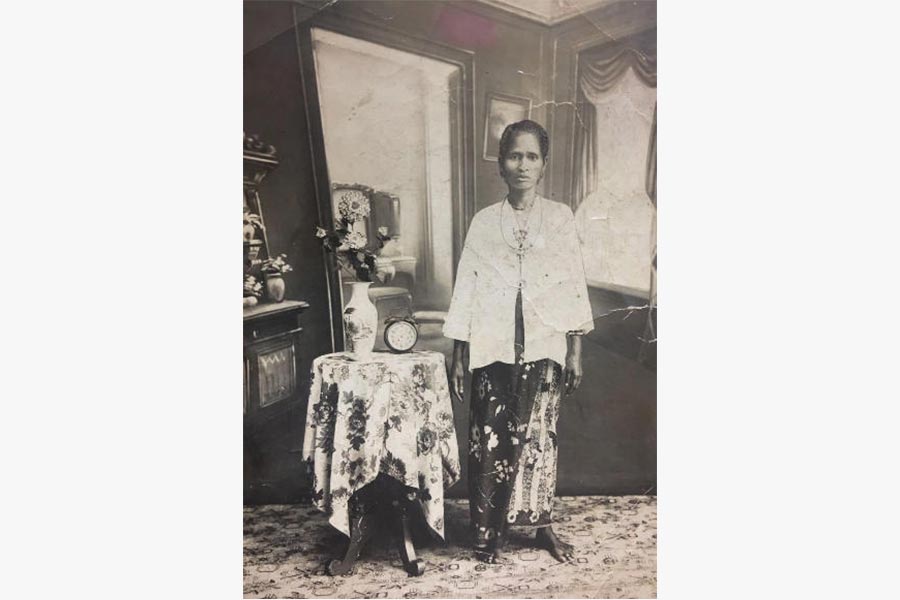

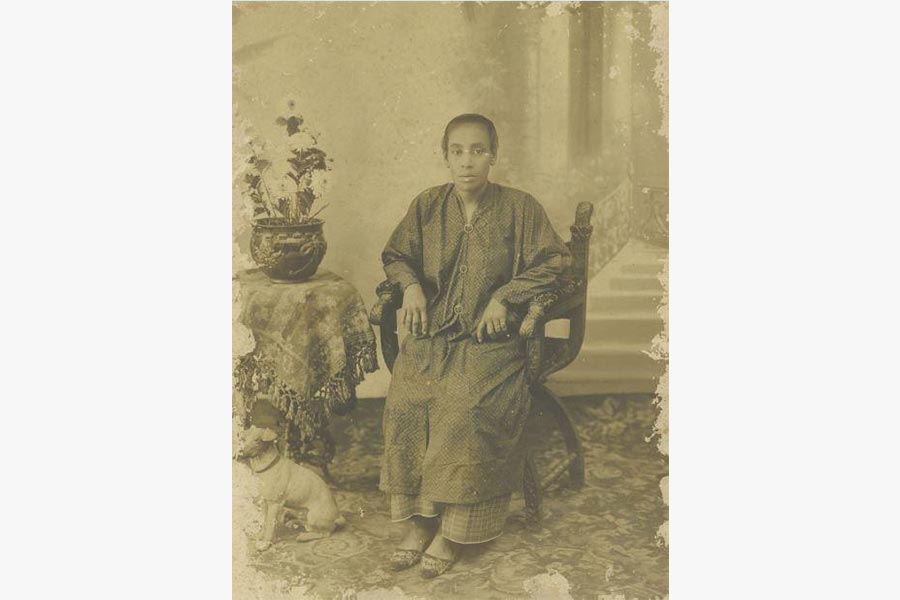

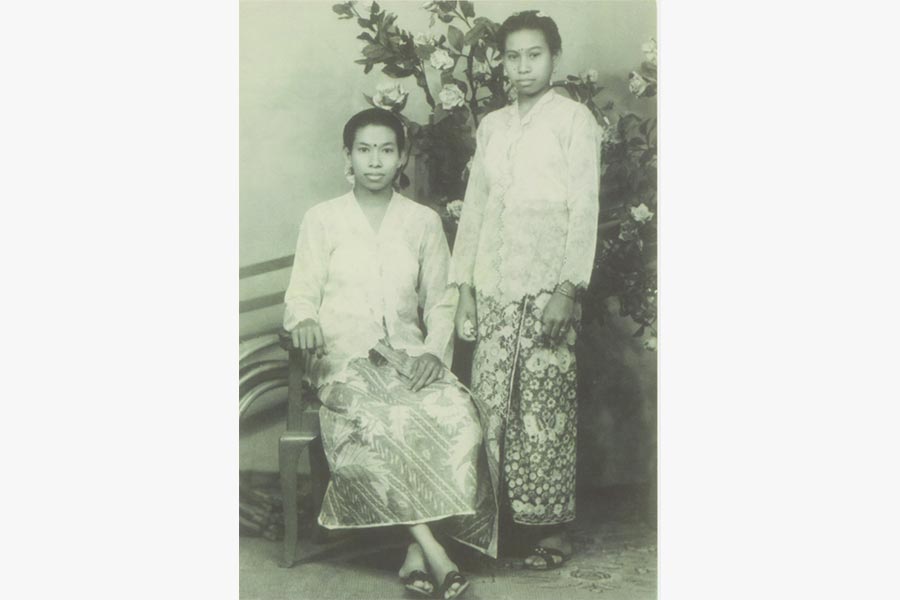

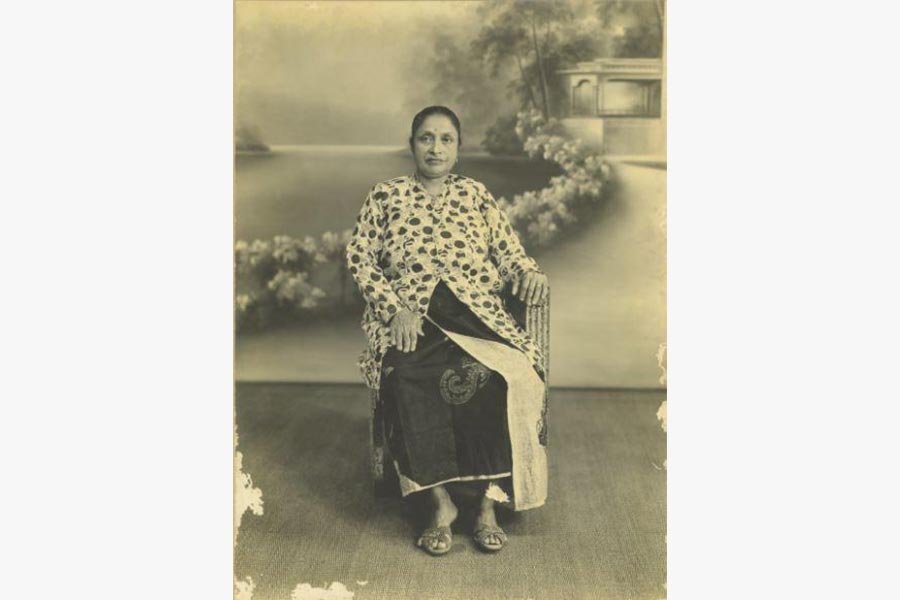

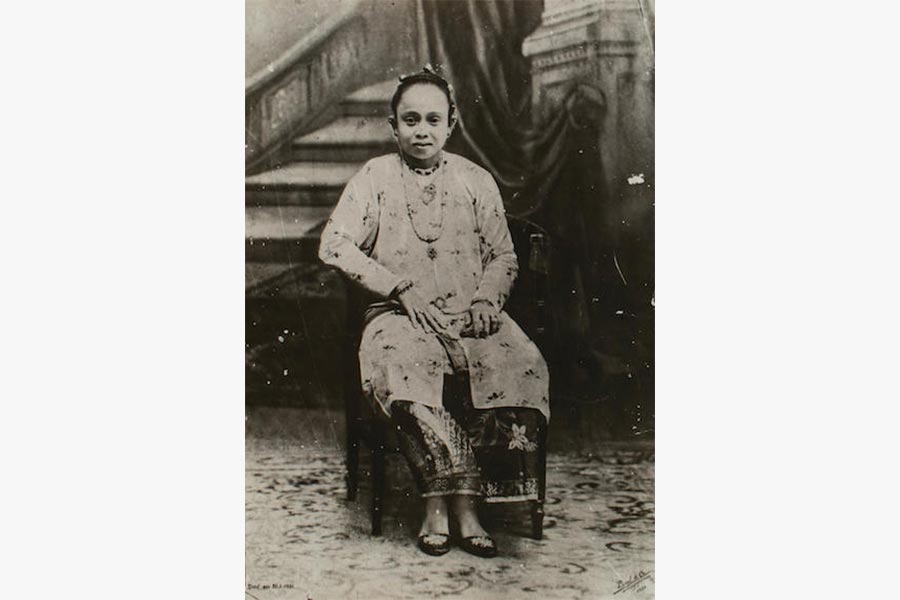

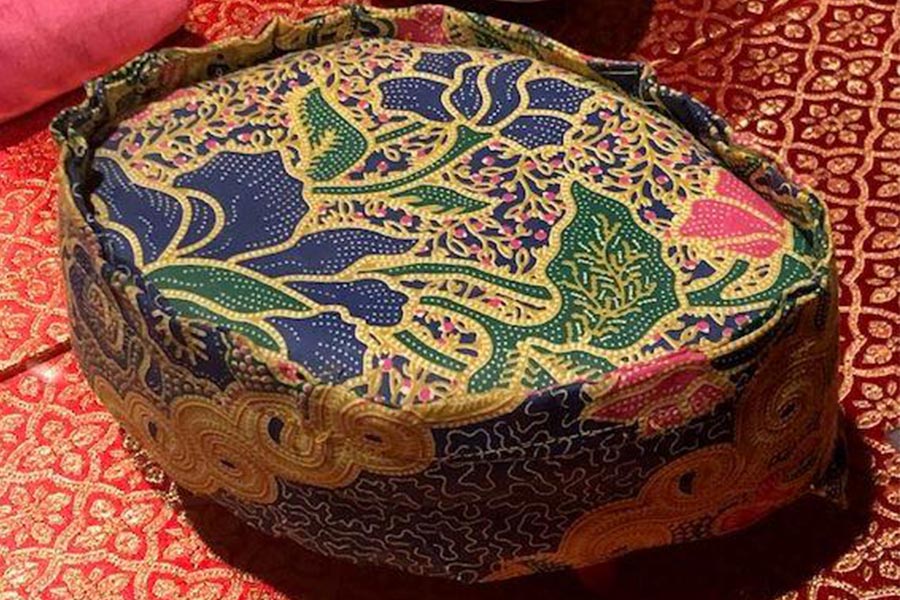

The traditional attire of the Chetti Melaka is an indicator of cross-cultural influences over time and mirrors centuries of Javanese, Bugis, Achenese, Batak and Tamil styles. Within the community, the traditional attire for men comprises a checkered sarong like the kain pulicat or the batik sarong, a tunic and a headgear of knotted batik cloth called talapa (headgear). Chetti Melaka men traditionally wore wooden clogs with silver pegs although these clogs have since been replaced by leather slippers.

The traditional attire for women comprised the sarong kebaya and the baju kurung, fastened with three keronsang(brooches). Affluent Chetti Melaka women also wore brooches made with gold studded with diamonds for their baju panjang. These brooches and other accessories were often crafted by Tamil goldsmiths, and featured elements such as addiggai (a gold choker usually studded with semi-precious stones), thali (a wedding pendant), and silambu (anklets).

In addition to local and Tamil styles, jewellery and accessories for women also reflected British influence and 20th century British gold sovereigns were often worn as pendants. The women also wore their hair in tight buns called sanggul nyonya which are held together using a combination of three hair pins, and their footwear comprised beaded slippers known as kasut manek-manek, which were often painstakingly handmade over many weeks.

Celebrating the Chetti Way

Watch: Celebrating the Chetti Way

Traditionally, the Chetti Melaka community were staunch followers of Saivite Hinduism and key Chetti Melaka festivals coincide with major religious events in the Tamil Hindu calendar. These include including Pongal (Harvest Festival), Mahashivratri (Festival of Shiva), Puthandu (Tamil New Year), Navaratri (Festival of Nine Nights) and Deepavali. As the Chetti community also includes many Christians, Christmas and Easter are also important festivals for the community.

The most important annual festival, Sembahyang Dato Chachar or Megammay Thiruvizha, is dedicated to the goddess Mariamman. During the festival, thousands of devotees attend the festivities held at the Muthu Mariamman Temple in Gajah Berang. Other temples such as the Kailasanthar and Angalamman Paramesvari, also host festivals dedicated to their central deities, such as Mahashivratri and Theemithi, albeit on a smaller scale.

While some festivals are celebrated at the temples, there are also many home-based observances and ritual practices. The most notable Chetti observances are the parachu prayers that take place twice a year – Bhogi in January and Parachu Buah Buahan in July. Both prayers are dedicated to ancestor worship and involve the preparation of special foods laid out in odd-numbered banana leaves for the ancestors to partake.

Although these festival related ritual practices were strictly adhered to in the past, few families outside Melaka continue to observe them when celebrating traditional Chetti Melaka festivals today.

From Cradle to Grave: Ceremonies and Rituals

Watch: From Cradle to Grave: Ceremonies and Rituals

The Chetti Melaka community’s lifecycle rituals and ceremonies closely follow traditional Tamil Hindu practices. They include coming-of-age ceremonies such as kaadhu kuthal (ear piercing) for both girls and boys, and the fertility ceremony sadanggu for girls to mark puberty. The latter 16-day long, female-only ceremony is held at home, and the girl is ritually bathed, given special foods and blessed by the women of the family.

The traditional wedding rituals for the Chetti community are elaborate, and the wedding typically takes place between four days to three weeks. The key components of a Chetti wedding include parisom (engagement ceremony), hantar sireh koil pathiram (delivery of the invitation card to the temple), berhinai (application of henna), menepah thali (making the wedding pendant), berarak (wedding procession) and the wedding ceremony itself.

The Chetti Melaka practice burying their dead and, according to traditional Chetti Melaka funerary practices, the deceased would be bathed, dressed and placed in a coffin, and carried by men to the cemetery. In Melaka and Singapore, deceased Chetti Melaka would be buried at Batu Berendam and Choa Chu Kang Hindu Cemetery respectively.

In Singapore, many Chetti Melaka life cycle rituals and ceremonies are rapidly evolving or even disappearing. Many Chetti families have forsaken traditional Hindu practices either because they have been assimilated through inter-marriage with other ethnic or religious communities, or because they have converted to other religions such as Christianity and Islam.

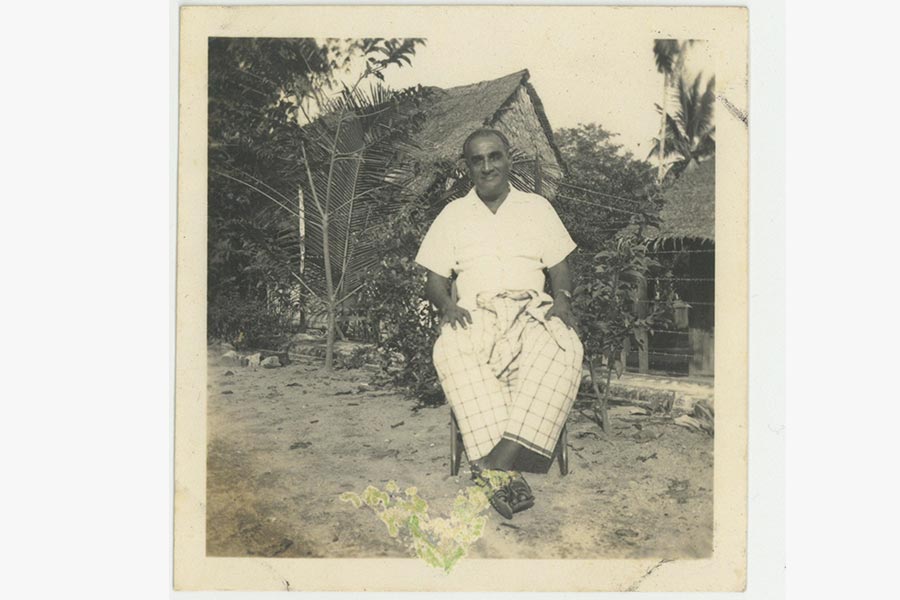

Family Ties

The Chetti Melaka in Singapore comprise a small community and they have been inter-marrying for several generations. Consequently, many of them are related or at least know each other. Due to its joint family system, the community has always been cohesive and share close relations. Till today, the elders in the family are very much respected, and some of the most important festivals for the community honour deceased ancestors.

The Chetti Melaka are conventionally orthodox with regard to naming practices, and they are given traditional Hindu names at birth. However, the Chetti Melaka also ascribe terms of endearment for all members of the family, and the meanings behind these nick names are known only to those near and dear. Nenek Jambol (grandmother with a special hairdo), Tok Puteh (a very fair lady), Krisna kechi (Krishnan who is short) and Mama Bulat (fat and round uncle) are but a few examples of Chetti nicknames.

As a result of migration, Chetti Melaka families were scattered across Melaka, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and across Malaya. Fortunately, the Chetti Melaka communities in Singapore and Melaka share close and strong bonds. For instance, several Chetti Melaka in Singapore continue to make donations to the temples in Melaka during festivals such as Sembahyang Dato Chachar, thus strengthening the bonds between the two communities.

The Way Forward

Watch: The Way Forward

In spite of being one of the region’s oldest communities, little is known about the Chetti Melaka of Singapore. They are a very small community, whose numbers are steadily declining, and their uniquely Straits heritage largely rests in the collective memory of the older members of the community.

Many members of the community, especially amongst the younger generation, have lost touch with their Chetti roots and a general lack of ready information about the heritage of the Chetti Melaka community has caused many of them to distance themselves from with their ancestry. Furthermore, as a result of generations of marriages outside of the community, many families are now unable to trace their Chetti Melaka lineage.

To further exacerbate the situation, the community is also faced with the dilemma of diasporic emigration, with several young Chetti Melaka migrating to Australia, North America, Europe and the United Kingdom. As a result, these emigrant Chetti Melaka are susceptible to newer multicultural influences which further render the contemporary Chetti Melaka identity more complex.

In the face of these challenges, the Peranakan Indian (Chitty Melaka) Association Singapore has played a crucial role in the revival of public interest in the community, and the way forward may lie in more sustained efforts to document and transmit different aspects of Chetti Melaka heritage and to increase public awareness and appreciation of the community’s unique language, cuisine and social-cultural practices.