Text by John Teo and Jackie Yoong

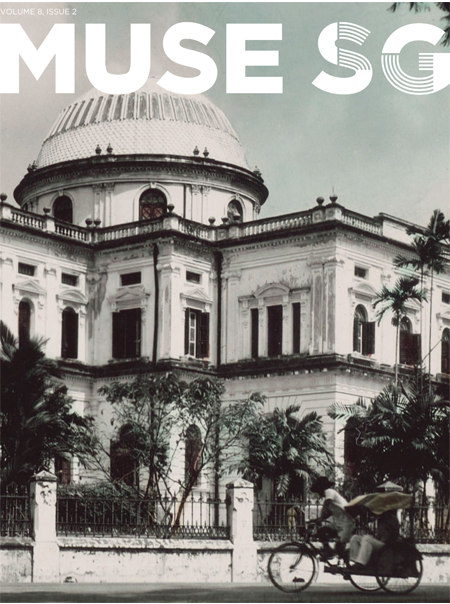

MuseSG Volume 8 Issue 2 - Jul to Sep 2015

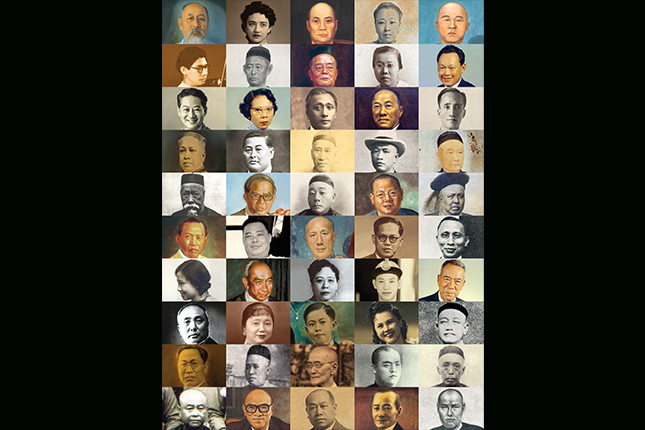

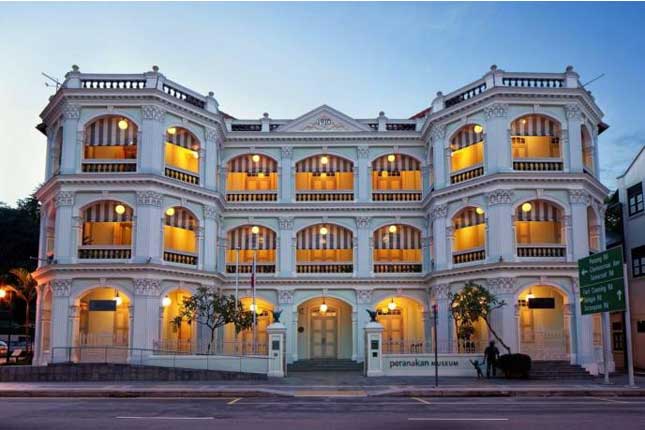

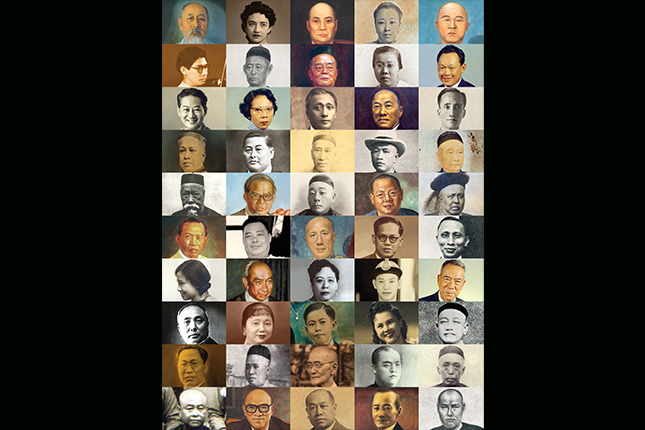

Tan Tock Seng, Goh Keng Swee and the late Lee Kuan Yew — all integral Singaporean icons, and all of them “Peranakan”. The Malay word “Peranakan” commonly refers to the creolized Chinese who lived in Southeast Asia. The community gained a reputation with its close ties to the British under colonial rule, but were also crucial players in Sun Yat Sen’s revolutionary activities and of course, our country’s rise since independence. In celebration of our country’s 50th anniversary, an exhibition showcasing the lives of 50 great Peranakans who contributed significantly to the development of our nation ran at the Peranakan Museum in 2015.

‘Great Men’

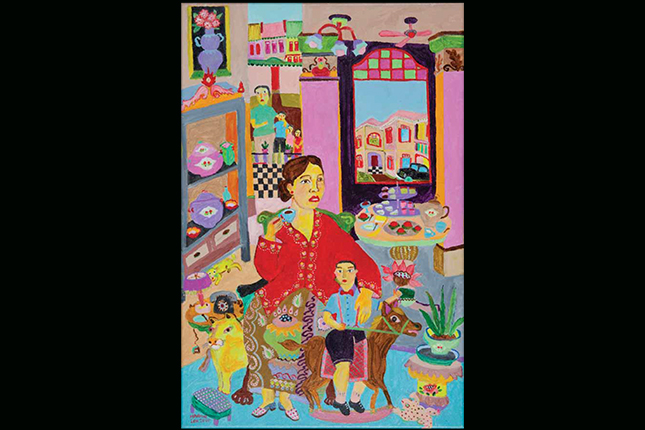

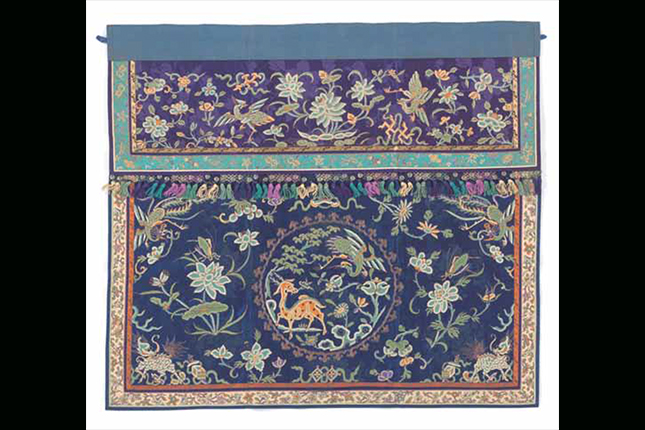

In our reading of Singapore’s history, we must not forget the pivotal role Peranakans have played in shaping it — from the obscure kapitans, the baba captains of industry, to members of our first Legislative Council. We must also dispel the myths and misconceptions surrounding the community. The Peranakans were not merely rich, English-educated dilettantes who collaborated with the British and Dutch colonial masters, nor were they part of the large migration of Chinese who came to Singapore to find a better life. Women are outnumbered in the selected group for the exhibition, which to a certain extent reflects the cloistered lives of nyonyas before the twentieth century. But while the lives of Peranakan women are not as well documented, their contributions are apparent in the community’s culture, including in the aspects of dress, food, residences, and social behaviour.

Crossing Boundaries

The Peranakans’ influence spread beyond the shores of Singapore. While the 50 featured in the exhibition were selected based on their contributions to Singapore, many were born and had made large impacts elsewhere. The community’s strong connections to Malacca, Penang, and Java highlight Singapore’s comparative newness as an independent entity. From 1819 to 1959, Singapore functioned as a British colony and the centrepiece of the Straits Settlements. Many of the individuals who found their way to the young nation also had connections and family networks throughout the region.

The Peranakans were quick to adapt to changing political circumstances. During the colonial period, they became powerful compradors and collaborators with the British and Dutch regimes. With the rise of Chinese nationalism in the late nineteenth century, some became crucial players in Sun Yat Sen’s revolutionary activities both within and outside China. Most leaders saw no contradiction in supporting both the British and the Chinese. World War II marked a turning point, after which some Peranakans began to champion for an independent Singapore and Malaya. The common caricature of Peranakans as “King’s Chinese” and their closeness to the British should not obscure their active engagement with Chinese culture and the Chinese community. Although many Peranakans lost their fluency and literacy in Chinese, they nonetheless supported Chinese or bilingual education, and founded Chinese newspapers. Some Peranakans converted to Christianity from around 1900, while others rediscovered Confucianism. Peranakans carefully balanced the two empires of British and Chinese. As they knelt loyally to receive visiting British royals, they also paid homage to Qing dignitaries. As some proudly received British decorations, they also purchased overseas Chinese honours.

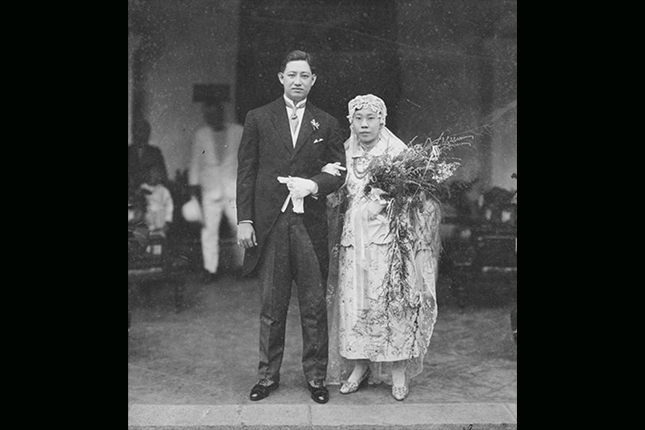

Beyond their national contributions, a study of institutional histories and memories related to the selected Peranakans has also revealed individual legacies. These are documented in temples, associations, churches, schools, hospitals, and private families, as well as in libraries, archives, and museums. Many of the objects shown in the exhibition are hybrid in form and design. The exhibition did not attempt to represent or define a Peranakan aesthetic, but, rather, celebrated the variety and inconsistencies within the community. Memoirs, interviews, and private collections paint intimate images of these exemplary figures. The objects featured in this exhibition ranged from spectacular furnishings, personal belongings, and rare portraits, to humble images, handwritten papers, and objects of everyday use.

One notable aspect of Peranakan families today is the extent of their knowledge of their past and their relations, whether by blood, marriage, or friendship. The Peranakan Museum is grateful for their generosity in supporting this exhibition and has been impressed by the strong sense of community and connectivity among Peranakans — ties which seem to have strengthened in recent years with the revival of interest in Peranakan culture. The Peranakans remind us that Singapore has long been closely connected with family and trade networks with the region — not only Penang and Malacca but also Jakarta and the rest of Java, and elsewhere. Taken as a whole, the biographies and objects on display in the exhibition illuminate not just the history of the Peranakans in Singapore, but that of the wider nation as well.

Tan Tock Seng

The First Community Leader 1798–1850

Born in Malacca, Tan Tock Seng moved to Singapore in the year it was founded by the British. He sold produce before building a fortune as a landowner in partnership with J. H. Whitehead of Shaw, Whitehead and Co. Tan was the first Asian to be appointed a Justice of the Peace in Singapore and is remembered principally for founding Singapore’s first hospital for poor Chinese.

At the request of the governor of Singapore, William Butterworth, Tan contributed $7,000 to start a public hospital. In 1844, the foundation was laid for the Chinese Paupers’ Hospital, which received its first patients in 1849. The hospital was named after Tan Tock Seng after his death in 1850.

Lim Nee Soon

Pineapple King And Chinese Nationalist Supporter 1879–1936

In 1911, Lim Nee Soon started a rubber and pineapple company. His large plantations in the booming pineapple industry soon earned him the nickname of “pineapple king”. A close friend of Sun Yat Sen, Lim became deeply involved in Chinese Nationalist politics. In 1904, together with Teo Eng Hock and Tan Chor Nam, he founded the revolutionary newspaper Thoe Lam Jit Poh (图南日报). Lim also participated in the founding of the Singapore branch of the Tong Meng Hui (同盟会), the Nationalist underground organisation. The organizers met at Teo Eng Hock’s house, Wan Qing Yuan (晚晴园), which is today the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall. In 1925, Lim became an honorary advisor to the president of China. He was given a state funeral in Nanjing and buried near Sun Yat Sen’s mausoleum.

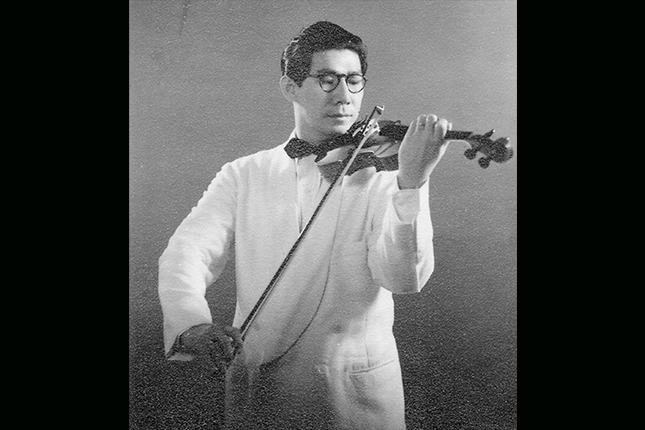

Goh Soon Tioe

Maestro and Impresario 1911–1982

Goh Soon Tioe was a pioneer in the development of classical music in Singapore. Born in Padang, Sumatra, he came to Singapore at the age of 13 to study at the Anglo-Chinese School. Goh only started violin lessons at the age of 15 but showed great promise, and in 1932 he left for Switzerland to join the Conservatoire de Musique de Genève, where he studied for three years. During his time there, he was awarded the “Premier Prix” — first prize — in each annual exam.

In 1954, Goh founded the Goh Soon Tioe String Orchestra. In the 1950s and 1960s, he ventured into concert promotion by bringing internationally renowned musicians to perform in Singapore. However, he was not able to continue organising these concerts because, as he observed, “costs are heavy and work is hard”. In his studio above a garage in Oldham Lane and later in his home in Balmoral Crescent, he taught many of Singapore’s musical prodigies, including violinists Lynnette Seah and Lee Pan Hon, pianists Seow Yit Kin and Melvyn Tan, and conductor Choo Hoey. Goh was awarded the Meritorious Service Medal in 1963 in recognition of his outstanding contributions to the music scene in Singapore.

Lee Choo Neo

Singapore’s First Female Doctor 1895–1947

Lee Choo Neo was Singapore’s first female physician. Breaking away from the tradition of the cloistered nyonya, she used her privileged position to help enact social reforms. Lee was the daughter of Lee Hoon Leong, a Peranakan from Semarang who was manager of Oei Tiong Ham’s shipping business in Singapore. Educated at the Singapore Chinese Girls’ School, she was the first Straits Chinese woman to obtain a Senior Cambridge certificate in 1911. She studied at the King Edward VII School of Medicine in Singapore, and became the city’s first Chinese female doctor in 1920. These were remarkable achievements considering the general Chinese cultural expectations of women’s roles.