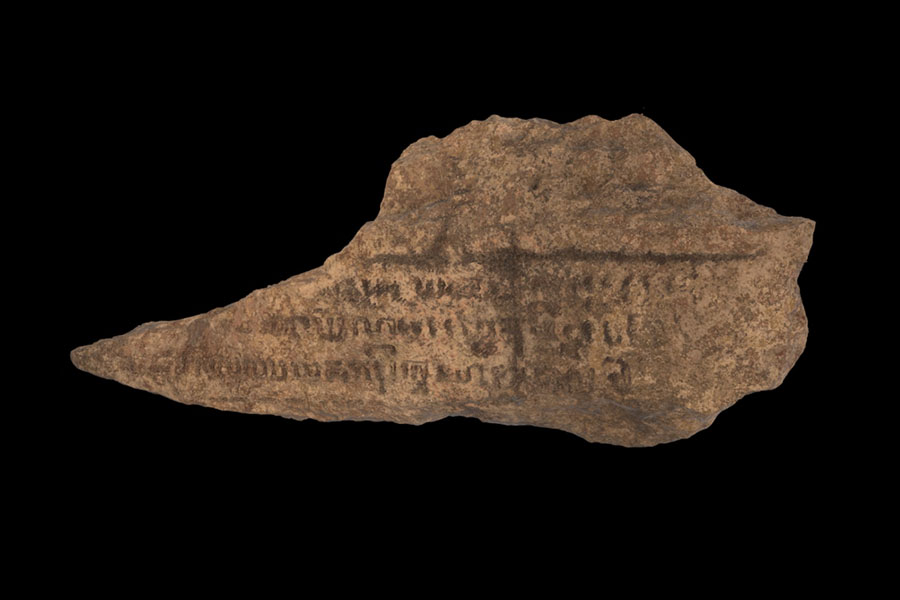

This year marks 200 years of the Tamils in Singapore. However, Tamil connections with Singapore can be traced as far back as the 11th–13th centuries CE based on recent interpretations of the Singapore Stone. From the Coromandel Coast to the Straits: Revisiting Our Tamil Heritage presents a compendium of narratives that recount the experiences of Tamil diasporas in Southeast Asia and Singapore from pre-modern to contemporary times.

Among the South Asian languages, Tamil is perhaps the only example of a very ancient language that still survives as the mother tongue of millions of speakers in south India, Sri Lanka, and of diasporas in many parts of the world. Singapore’s Tamil community is distinct as they have adapted and integrated with local cultures. Primarily born out of the colonial enterprise, the Tamil community is today a vibrant part of Singapore’s multi-ethnic fabric.

This exhibition is presented in two parts: part one enumerates the odyssey of pre-modern Tamil diasporas in Southeast Asia while part two offers glimpses of lesser known 19th century pioneers and some of the oldest Tamil families in Singapore. Bringing together collections from around the world and treasured possessions from the community, this exhibition seeks to present an uninterrupted history of Tamils in Singapore. It also includes digital showcases featuring holograms of artefacts in the collections of other museums and institutions.

Cholamandalam to Coromandel

Coromandel was a region known around the world for its trade textiles and goods from ancient times. The term “Coromandel” is the European derivative of Cholamandalam (“the realm of the Cholas” or “the land successfully conquered by the Cholas”). Also known as Chola Nadu or “land of the Cholas”, Coromandel referred to territories under the Chola dynasty in south-eastern India which included parts of present day Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Andhra Pradesh.

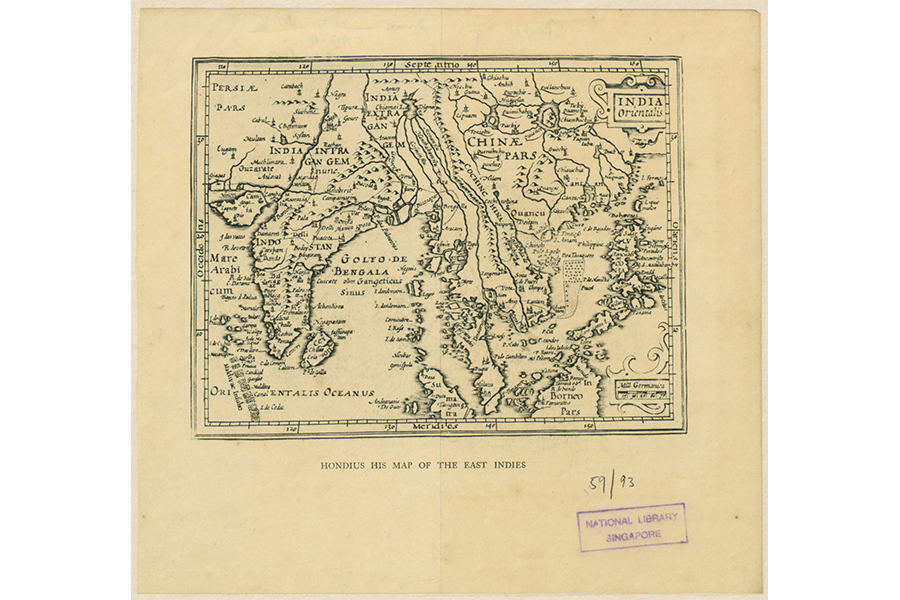

The earliest reference to Cholamandalam can be found in an inscription located at the Brihadishvara Temple in Thanjavur dating to the 12th century CE. The oldest European mention of Coromandel appears in Roteiro de Vasco da Gama (Journal of the First Voyage of Vasco Da Gama) as Chomandarla. As a toponym, Coromandel first appears in Portuguese maps at the start of the 16th century.

The Coromandel coastline was a significant trading region in the Indian Subcontinent. It was home to a network of ports such as Pazhaverkadu, Nagapattinam, Parangipettai, Arumugam etc. which were unified by their participation in the Indian Ocean trade. By the 17th century, established mercantile communities were concentrated around ports along the Coromandel Coast.

For instance, in Southeast Asia Tamil Muslim trading communities from the Coromandel Coast such as Lebbai, Rawther, Marakayyar and Kayalar achieved fame as the Chulia merchants. These traders were engaged in commerce primarily with Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the Melaka Straits and other parts of Southeast Asia, although this trade gradually declined by the 19th century.

PART 1 TAMILS IN PRE-MODERN SOUTHEAST ASIA

Ancient Connections

Maritime links between South India and Southeast Asia date back to the late prehistoric period. During this period, Tamils acted as intermediaries in a trade network comprising the Roman Empire and the Mediterranean in the west to the other side of the Bay of Bengal. By the early centuries of the Common Era, pre-modern Tamil diasporas comprising seafarers and traders travelling to ports in Southeast Asian polities, had become common.

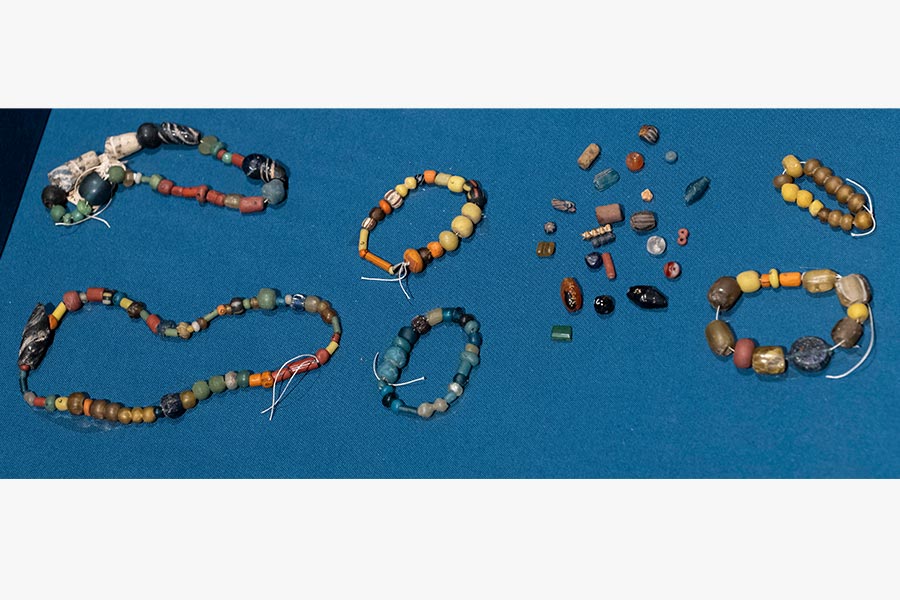

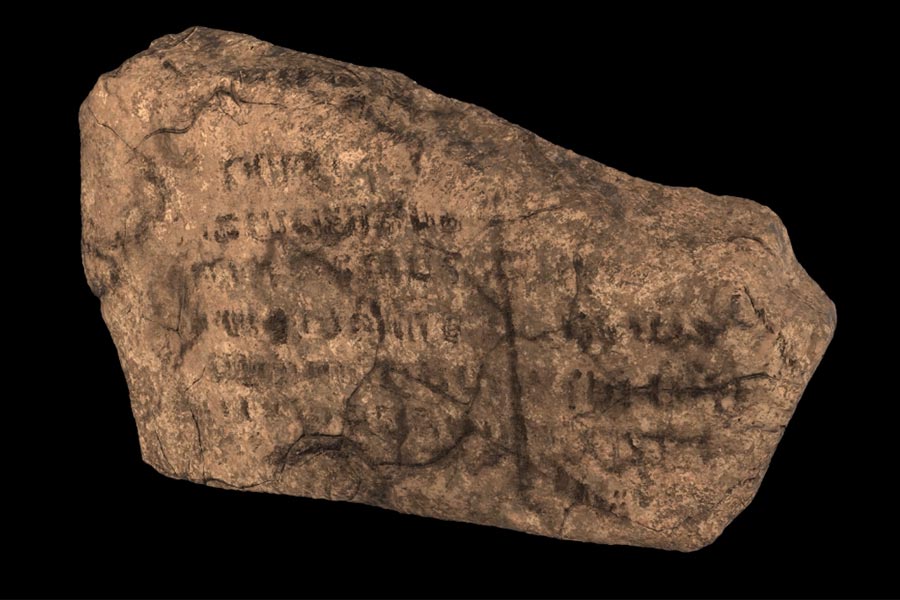

The early presence of Tamils in Southeast Asia is supported by epigraphic and archaeological finds that include medieval Tamil inscriptions, coins, pottery, ceramics, beads and bronze artefacts. The oldest inscription in the Tamil language dates to the 2nd or 3rd century CE on a potsherd found at Phu Khao Thong in south Thailand bearing the word turavon, meaning “ascetic”. A 3rd century CE touchstone inscription of a perumpattan (Tamil goldsmith) from Khuan Luk Pat in Krabi Province points to the presence of pre-modern professional diasporas. The Takua Pa inscription indicates that a manigramattar (Tamil mercantile guild) operated in Thailand in the 8th–9th centuries CE. The Lobu Tua inscription also mentions the Ayyavole trade guild who established a permanent outpost on the west coast of Sumatra. In addition, the Sangam anthologies contain the earliest literary references to Tamil contact with Southeast Asia. The poem Pattinappalai, dating to the 2nd century CE, describes the import of foreign merchandise from Kedah to the Chola port of Poompuhar, while Chithalai Satthanar’s Manimekalai written in the 5th–6th centuries CE makes reference to Java.Empires and Faith

The earliest reference to Tamil religious beliefs can be found in Sangam literature. Each of the Sangam thinai (poetic landscape) was represented by a specific deity: Kurinji or hilly regions by Seyon or Murugan; Mullai or pastoral lands by Mayon or Vishnu; Marudam or agricultural areas by Senon or Indra; Neydal or coastal zones by Kadalon; and Palai or arid regions by Korravai.

Jainism and Buddhism also co-existed with Hindu practices during this period. For instance, Kanchipuram, Puhar or Kaveripumpattinam, and Madurai were known as the three ancient Tamil centres of Buddhism. Even the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang visited the court of Narasimha Pallava in the 7th century CE and noted that there were 100 Buddhist monasteries and over 10,000 monks.

From the 7th century CE onwards, a devotional movement revived the Hindu sects of Siva and Vishnu as well as the worship of the mother goddess or Shakti. The classical form of Tamil temple architecture evolved after this period with the rise of the Pallava, Cholas, and Pandiya dynasties. Echoes of these art and architectural styles can be seen across Southeast Asia as remnants of its Hindu-Buddhist past.

Tamil folk versions of the Ramayana and Mahabharata also grew popular in Southeast Asia. For instance, the Ramakien’s inclusion of Mayil Ravanan, a character unique to Kambar’s Ramavataram, points to the Tamil influences in the narrative.

Coromandel Trade

Mercantile activity between the Tamil country and Southeast Asia was well in place long before the arrival of European companies in the region. For instance, Sultan Mansur Shah of Melaka (1459–1477 CE) sent emissaries to the Vijayanagara Empire in the 15th century to strengthen commercial ties, and the ships of the Sultan of Melaka sailed to Pazhaverkadu or Pulicat regularly.

Tamil traders such as the Marakkayars, the Mudaliars, and the Chettis were held in high esteem in the courts of Southeast Asian kingdoms and were made shahbandar (harbour master), bendahara (official) and saudagar raja (king’s merchant). They hailed from port towns such as Pazhaverkadu, Mylapore, Kunimedu, Cuddalore, Parangi Pettai, Nagore and Nagapattinam, and exported rice and textiles from the Coromandel in exchange for gold, copper and tin; spices such as nutmegs and cloves; and Chinese raw silk.

Nayinar Chetti, a native of Pazhaverkadu, was a leading textile trader in 16th century Melaka and appointed shahbandar by the Portuguese. Tome Pires in Suma Oriental mentions Nayinar Surya Deva, a well-known merchant who was engaged in trade from Melaka to the Moluccas. The Sultan of Banten appointed a Chetti merchant from Mylapore as laksamana (supreme commander of the navy). In the early 17th century, the Sultan of Pasai appointed Nayinar Kuniyappan, a Hindu merchant from Kunimedu as shahbandar.

However, the influence of these Tamil trading communities declined by the 19th century.

Arikamedu

The Coromandel Coast included ports located across present day Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. Arikamedu was one of the most important ports in this network, and had connections with Southeast Asian centres such as Khao Sham Kaeo in Thailand and Sembiran in Indonesia. Rouletted pottery and beads made in and/or by communities from Arikamedu recovered from these sites serve as evidence of these early connections.

The Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, in the early centuries of the Common Era, mentions Arikamedu as the port for Colondiphonda (an unknown type of ship) bound for Southeast Asia (Cheryse). Arikamedu was a significant production centre with strategic access to the Indian Ocean trade network.

Kedah

Kedah was an important trade centre and ancient kingdom in the Malay Peninsula. Early south Indian navigators often relied on latitudinal readings, and their ships would sail in a straight line from southern India or Sri Lanka across the Bay of Bengal and make landfall at the Isthmus of Kra or at Kedah. Known in Chinese sources as Jiecha and as Kadaram in Tamil country, it was an ideal midway point for traders and pilgrims awaiting favourable monsoon winds to take them to their ultimate destinations in India and beyond or China.

The earliest references to Kedah can be found in Sangam literature composed in the second half of the 2nd century CE. Called Kazhagam in Pattinapalai, this term is derived from the Tamil word kazhk meaning iron or black rock. This type of iron was typically used to forge steel weapons which were then exported out of iron factories. Archaeological excavations in Kedah have led to the discovery of iron factories at the Sungai Batu dating back to the 3rd–6th centuries BCE.

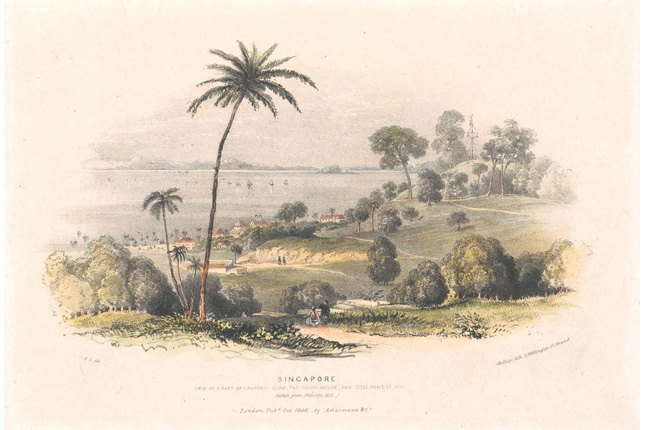

The Singapore Connection

Archaeological finds since the 1980s in the riverfront area strongly suggest that maritime networks connected India to the kingdom of Singapura, a prosperous regional port for much of the 14th century CE. Situated at the access points of both the Straits of Malacca and the South China Sea, this port was of strategic significance and was central in the lucrative India-China trade.

Sang Nila Utama, of the Srivijayan dynasty, founded the kingdom of Singapura in the late 13th century CE. He and his descendants ruled Singapore for five generations until Iskander Shah fled, driven out by Majapahit forces. He later founded the kingdom of Melaka. As attested in the Sejarah Melayu or Malay Annals, these kings of Singapura claimed descent from Raja Chulan of the Chola dynasty.

The victories of Chola kings in the Malay Archipelago are listed in inscriptions of the era. Thirteen place names are provided, of which four are unidentified till date. Some scholars have recognised one of these names, Valaippanduru, as Singapore, as Pancur was the placename for Fort Canning Hill at the heart of Old Singapura.

The name Singapura itself has Indic roots and it was likely adopted due to connections with South Indian polities. For instance, Singapuram was a common placename issued in the Chola territory while Singai Nagar was the capital of the Arya Chakravartis of Jaffna. Singapura was also the name of places in Tra Kieu, Vietnam as early as the 4th century CE.

Odyssey of Tamils - From the Coromandel Coast to the Straits

Odyssey of Tamils, a specially commissioned documentary film, dwells on the pre-modern connections between Tamil regions, Southeast Asian polities and Singapore. Utilising evidence of Tamil connections in archaeological sites, museums and other institutions, this film presents the rich legacy of Tamil heritage in the region during pre-modern times. It also shows Singapore’s contemporary Tamils visiting sites of historical importance, and reminds us that our heritage is all around us, waiting to be re-discovered.

This film uses authoritative accounts presented by historians Iain Sinclair and Sureshkumar Muthukumaran on the role of Tamil diasporas in Southeast Asia and Singapore. From surveying early literary references to a toponymic review of cross-cultural interactions, the film features aspects of interactions between south Indian and Southeast Asian societies from ancient times.

It also investigates traces of the Cholas in Singapore through Dr Iain Sinclair’s survey of 14th century archaeological finds and the Singapore Stone in conjunction with narratives presented in Sejarah Melayu. Using a combination of re-enactments, interviews and contextual imagery, this film presents the odyssey of early Tamil diasporas in Southeast Asia and Singapore.

PART 2 TAMILS IN 19TH CENTURY SINGAPORE

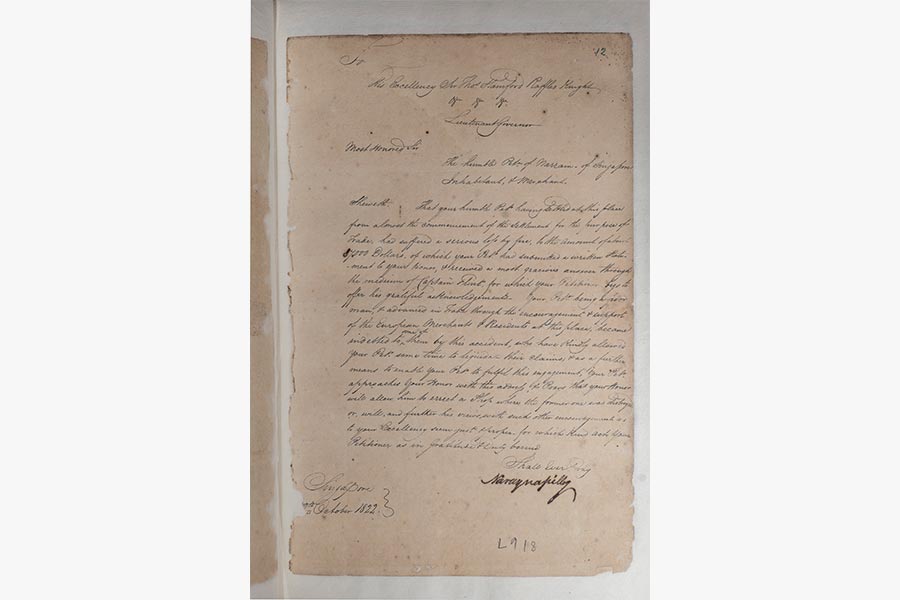

Merchants: Naraina Pillai and his Contemporaries

The early Indian mercantile community in Singapore was diverse in ethnicity and religious affiliation and Tamils were influential merchants, traders, shopkeepers and small vendors. The Chulias were among the earliest Indians to settle permanently in Singapore, and by the 19th century, they had become one of the most influential sections of the Tamil community as leading operators of lighter and harbour boats, as well as shopkeepers and labourers. As early as 1827, Tamil Muslim migrants, led by Anser Saib, were given land for the construction of a mosque along South Bridge Road while Mohammed and Haja Mohideen constructed the shrine Nagore Dargah between 1828 and 1830.

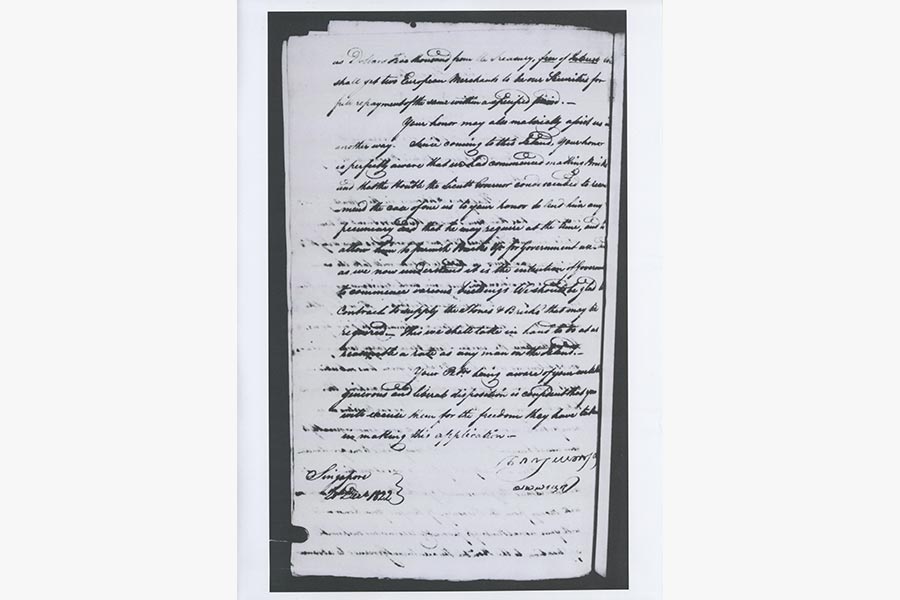

Between 1823 and 1826, Sir Stamford Raffles introduced regulations to select and appoint headmen based on their respective community’s customs and social practices to deal with disputes. In 1822, William Farquhar, the Resident of Singapore nominated Sangra Chitty, a Hindu native of Malacca, as the overall headmen for the Indian community and Naraina Pillai, and Mayapoory or Viapoory, as the headmen for Coromandel Coast natives. In addition, Mahomet Lebbai, Fakir Tyndall and Ibrahimutto were nominated as headmen for labour while Mahomud Hussein, Ismail Lebbai and Sheikh Mahomet were nominated to represent the Tamil Muslim community.

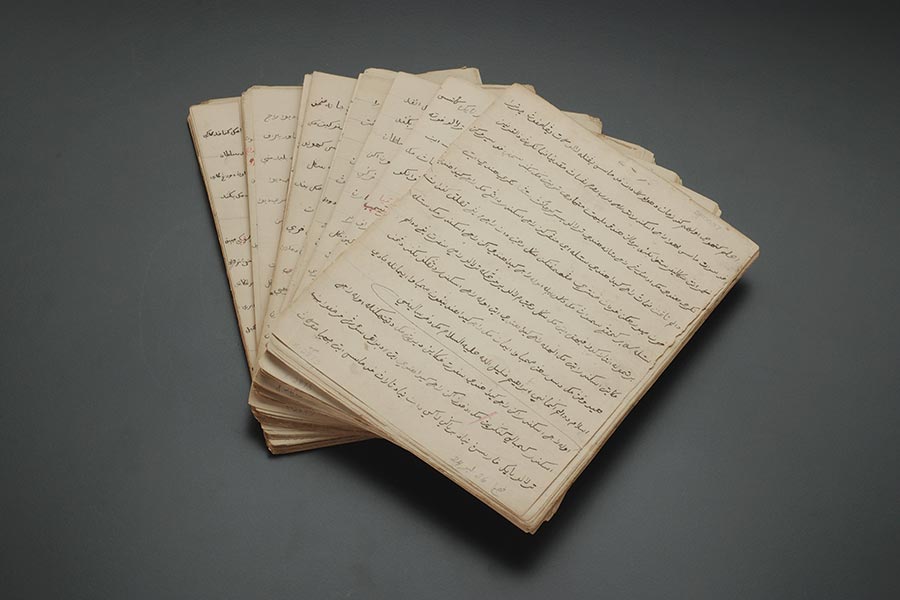

Scribes, Poets and Publishers: Munshi Abdullah, Makhdoom Saibu, and Others

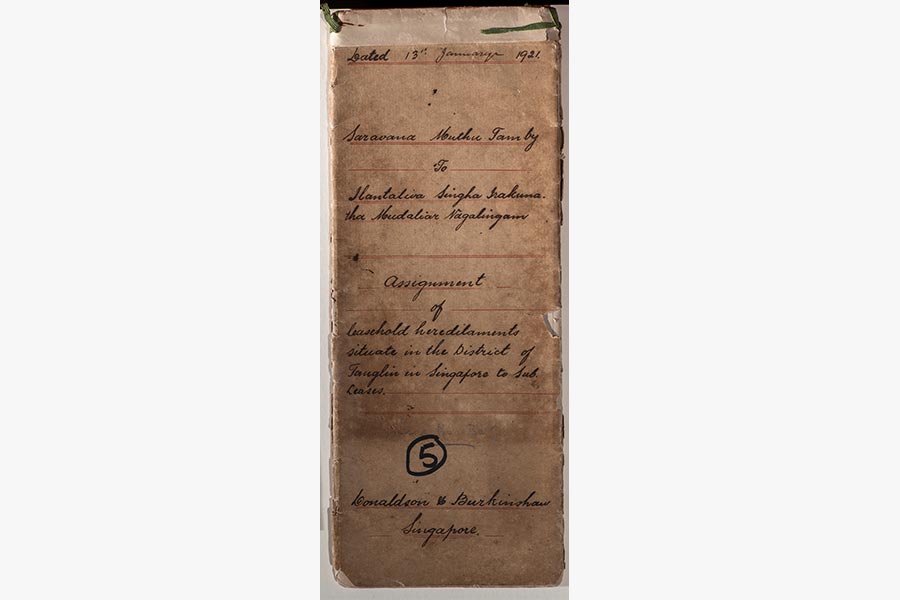

19th century literature attests to the diversity of early Indian residents in the Straits region. Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, better known as Munshi Abdullah, arrived in Singapore from Malacca in mid-1819, and served as a scribe and interpreter for Sir Stamford Raffles. The first historical accounts on Indians in the Straits Settlements were available in the 1920s and 1930s following the publication of Saravana Muthuthamby Pillai’s Malaya Manmium on Tamils in Malaya, PNM Muthupalaniappa Chettiar’s Happy Malaya and RB Krishnan’s Indians in Malaya.

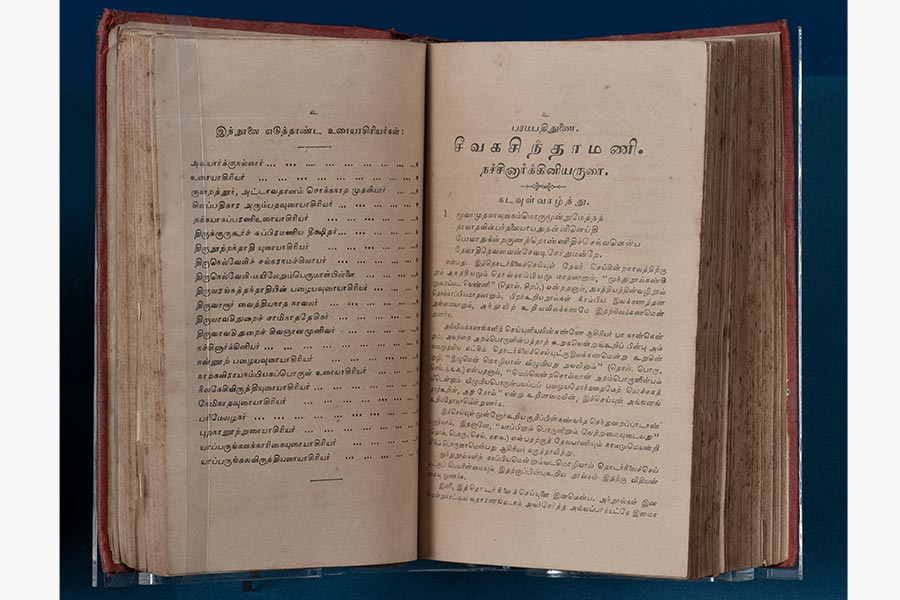

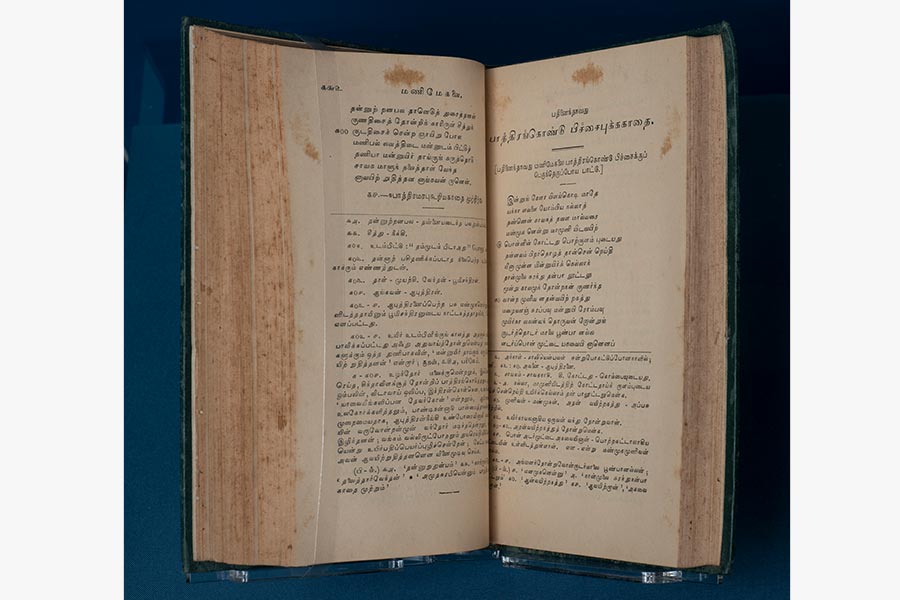

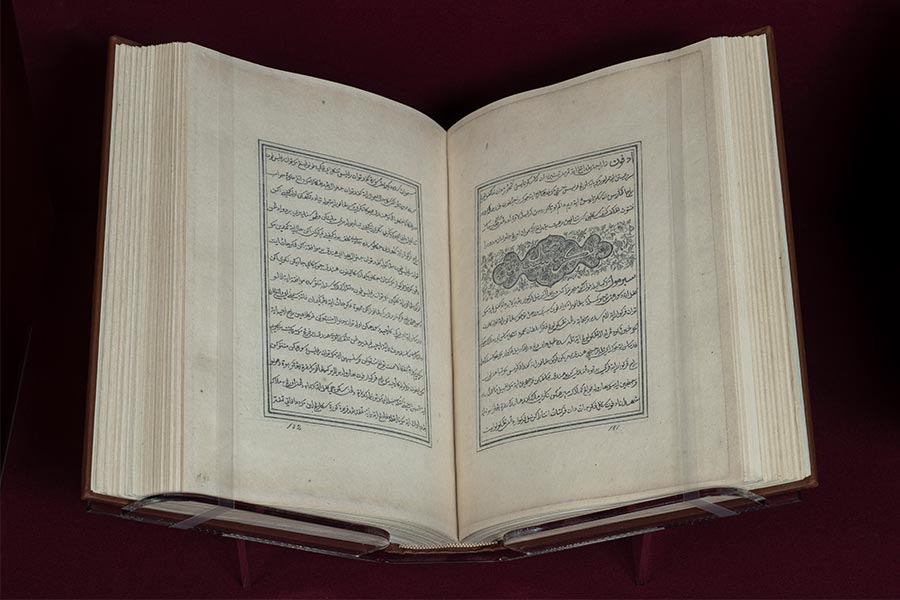

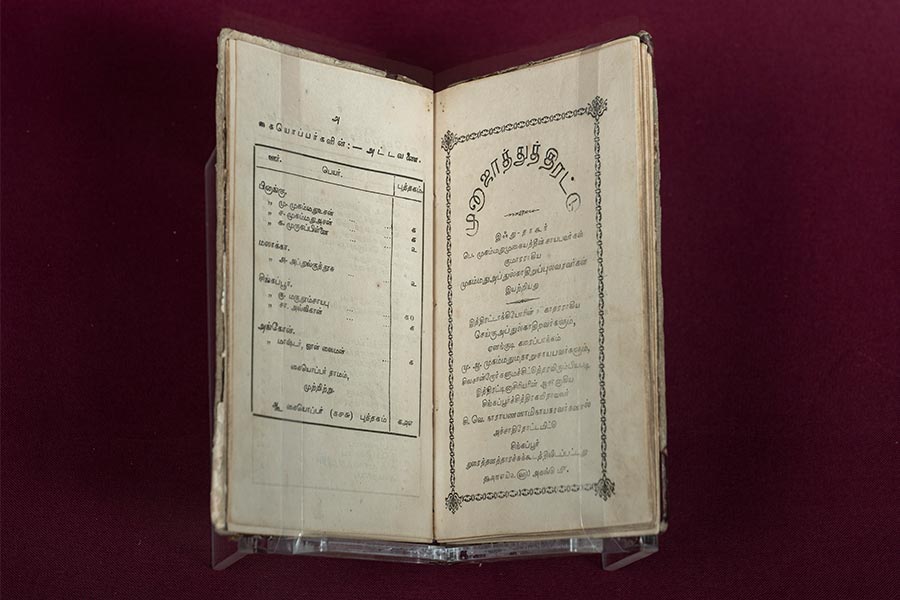

Tamil literature in Singapore, however, pre-dates the abovementioned publications and can be traced to the late 19th century. Examples include Munajathu Thirattu by Muhammad Abdul Kadir Pulavar, a compilation of Islamic religious poetry, which was published as early as 1872, and Singai Nagar Anthadi by Yazhpanam Sadasiva Pandithar in 1887. By the second half of the 19th century, Tamil Muslims and the Jawi Peranakans established the earliest vernacular presses in Singapore. These newspapers were published in Tamil and provided commentaries on subcontinental politics, social reform and local issues.

In 1873, CK Makhdoom Sahib established Denodaya Press which published Singai Varthamani, Singapore’s first Tamil newspaper in 1875. In 1876, the Jawi Peranakan company published Tankai Nesan, and in 1887, the Denodaya Press published Singai Nesan. In 1907, NR Partha founded and edited The Orient newspaper, and its Anglo-Tamil version Vijayan with a view to better understand the island’s residents. Other notable Tamil newspapers published during the early 20th century included Tamil Murasu by the Tamils Reform Association and edited by G Sarangapany.

Bankers and Patrons: The Story of the Rm VLN Chettiar Family

Nattukottai Chettiars are one of the oldest Tamil communities in Singapore and they settled in Singapore during the 1820s. As a community of private financiers and merchant bankers, the Chettiars were the main source of private financing through medium and long-term credit, and their clientele was cosmopolitan. They were also keen advocates of education and established the Chettiar’s Premier Institution. In addition, the Chettiars built Sri Thendayuthapani Temple on Tank Road in April 1859, and the popular festival-procession of Thaipusam dedicated to Murugan was first celebrated at the temple in 1860.

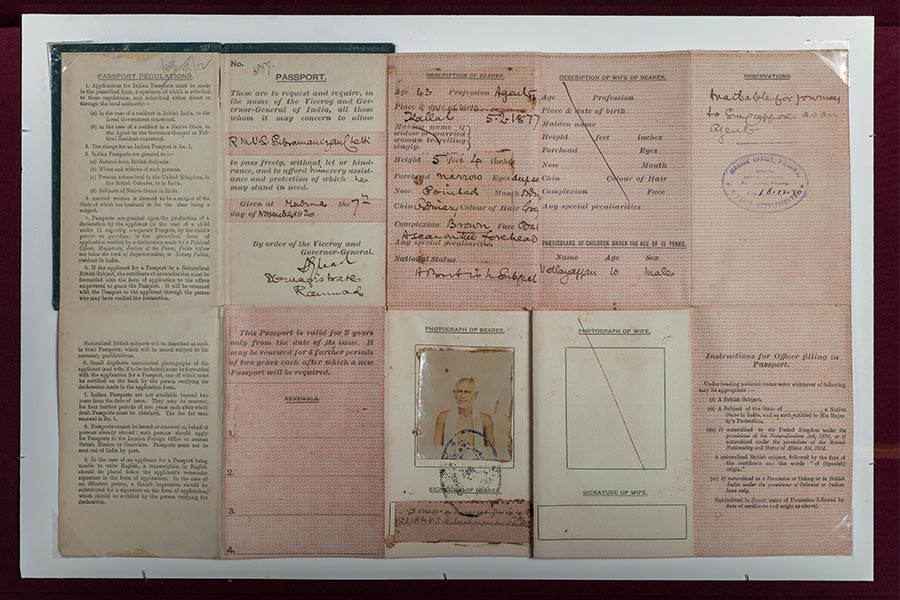

The family of Rm VLN (Ramanathan Vellayappan Lakshmanan Nachiappan) Subbiah Chettiar has its roots in Kallal in Chettinad. Rm V Subramaniam Chettiar arrived in Singapore in 1892. He was a private financier and with his brother Lakshmanan Chettiar, co-founded his firm located at 56 Market Street. Lakshmanan adopted Subramaniam Chettiar’s son Nachiappan who continued in the financing business, and his son Rm VLN Subbiah Chettiar was the last of the private financiers in this family. The practice of retaining the initials of several generations in their name is unique to the Chettiar community and provides a clue to a Chettiar’s genealogy.

This is one of Singapore’s oldest Nattukottai Chettiar families with a long history in Singapore dating back to the 19th century.

A Fleet of Carriages: The Story of Sangoo Thevar and Descendants

In the early 19th century, Singapore’s land transport system was comprised mainly bullock carts, horse carriages, jin-rickshaws and bicycles. Sangoo Thevar, Palaniappa Chetty, Sundra Daven, Meydin, Ismail Shah and Syed Ibrahim were some of the Tamil horse carriage contractors. Sangoo Thevar (Sangoo is Tamil for conch) arrived in Singapore in the 1850s with his wife from Mannargudi, Thanjavur. He acquired a fleet of horse carriages and leased them out.

In the succeeding decades, he amassed a fortune from this business and became a prominent member of the Indian community in Singapore. Sangoo Thevar had six children, Shanmugam Pillai, Parvathi, Regunath, Rajagopal, Lakshmi, and Meenachi Sundram. When Sangoo Thevar passed away in 1890, Shanmugam, the eldest, remained in Singapore and sent his siblings and mother back to India in 1895. Shanmugam subsequently became the Chief Clerk of Singapore Telegraph Office in 1912. Sangoo Thevar’s youngest son, Meenachi Sundram, returned to Singapore in 1912 with his mother and later became the first Asian Headmaster of Anglo-Chinese School in Singapore.

Sangoo Parvathi's daughter Anjalaiammal married Avadai Thevar, a construction contractor who arrived in Singapore in the early 20th century from Thanjavur, and their daughter, Avadai Dhanam, became the first lady of Singapore as the wife of the late CV Devan Nair, third President of the Republic of Singapore.

From Vaddukoddai to Singapore: Annamalai Pillai, JA Supramaniam and Descendants

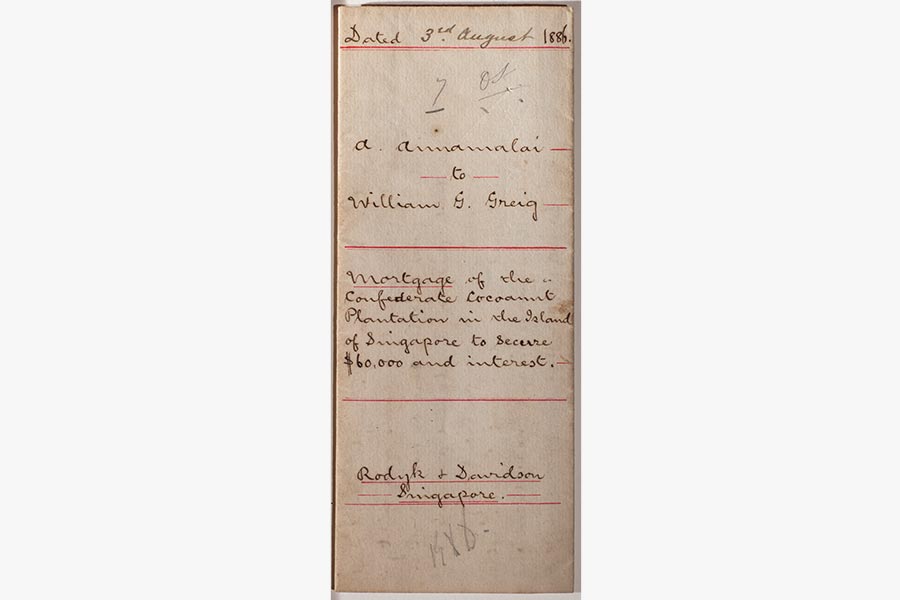

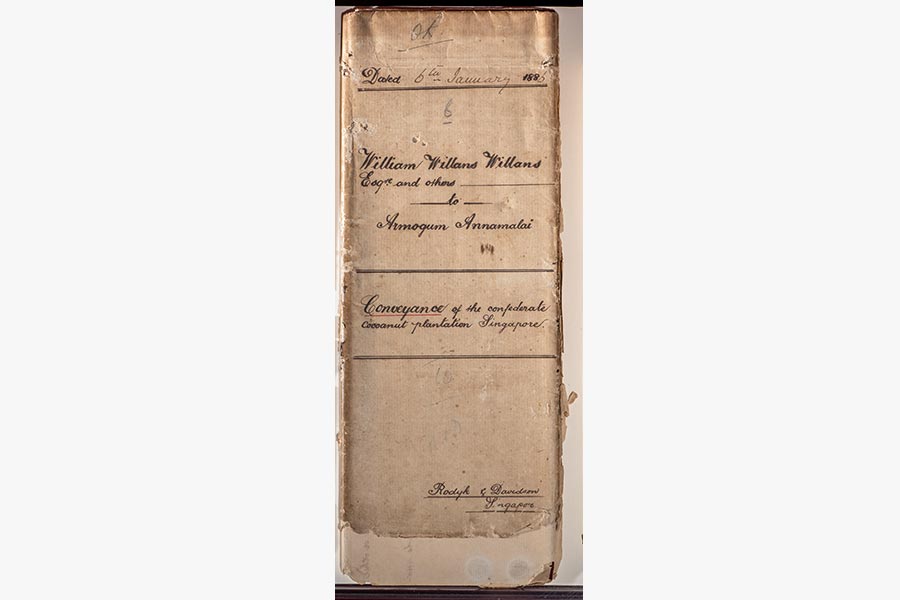

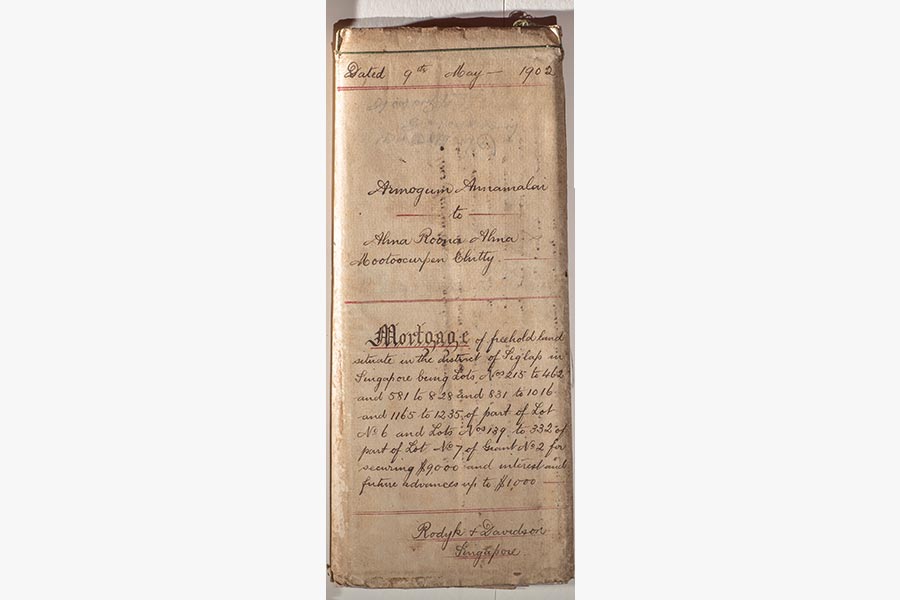

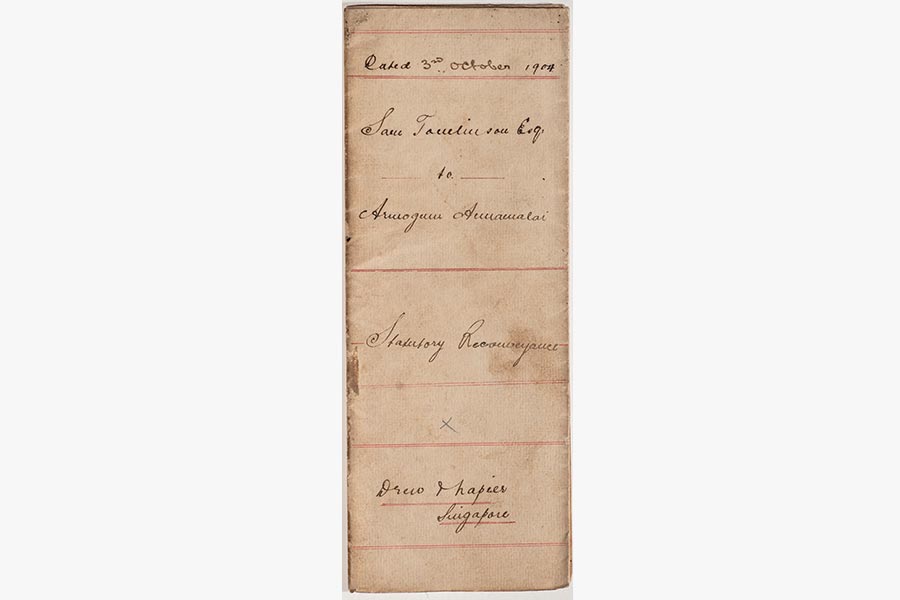

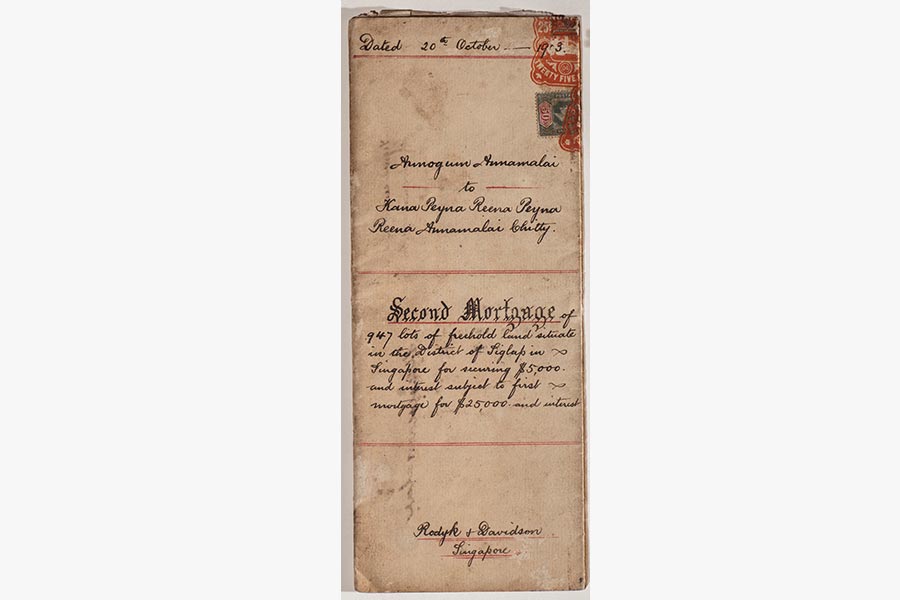

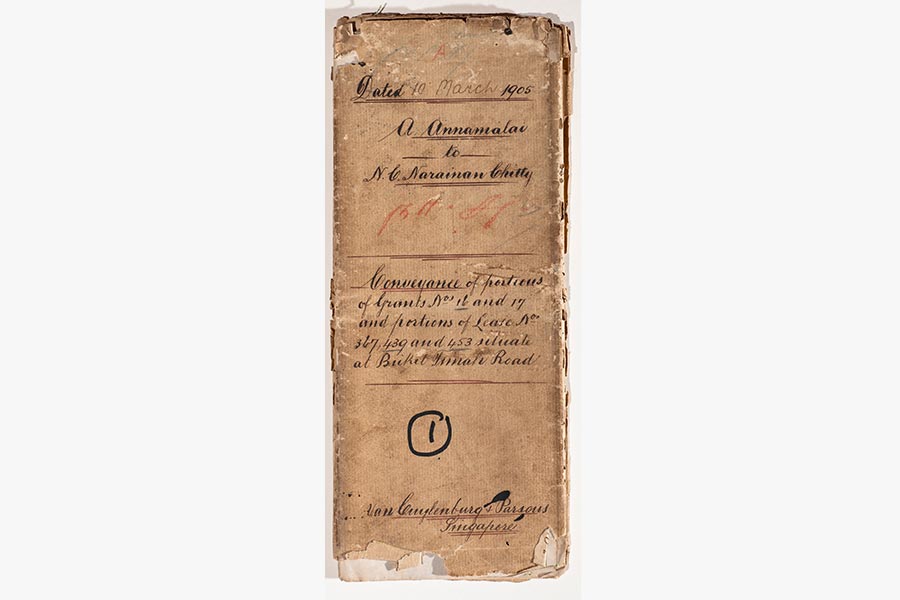

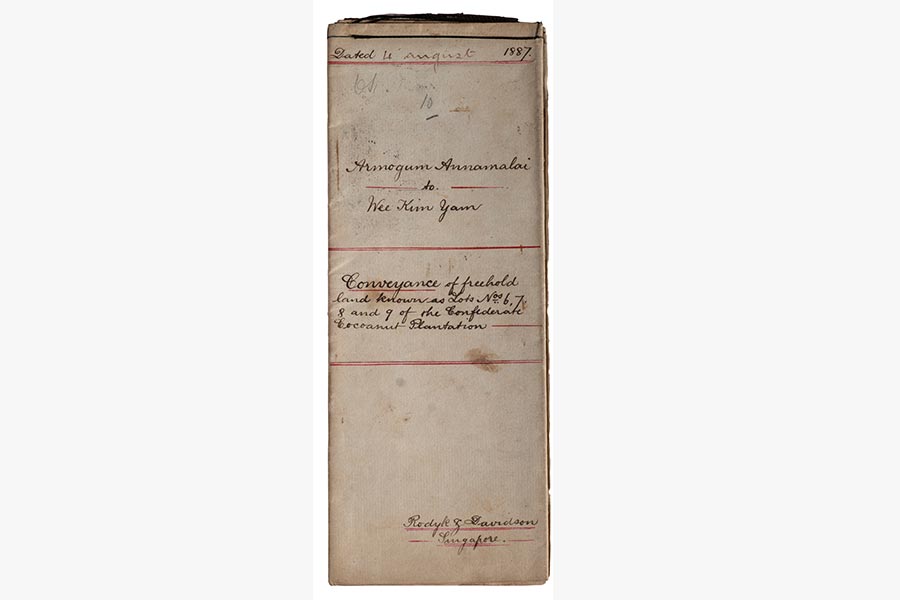

Arumugam Annamalai Pillai was born in Vaddukoddai, Jaffna in 1839. He was educated at St John’s College in Yazhpanam or Jaffna and later graduated as a surveyor in India in 1868. He was appointed Government Surveyor at Galle where he met James Wheeler Woodford Birch. Birch later became the Colonial Secretary of Singapore and transferred Annamalai to Singapore to become its Government Surveyor.

Annamalai arrived in Singapore in 1875 and became Chief of the Survey department. Annamalai introduced the practice of valuing land in Singapore by the square foot as he anticipated the rise in land value as the port city developed. He resigned from colonial service in 1883 and established a leading private practice in partnership with Alfred William Lermit. It is estimated that Annamalai was responsible for surveying three quarters of the land in Singapore. According to title deeds and historical records, Annamalai owned estates in Katong and Siglap by 1885. He also started buying tracts of land in Tanglin and the Bukit Timah area, and these surroundings were collectively named after him as Namly Avenue. Annamalai Pillai was also a founding member of Singapore Ceylon Tamil Association.

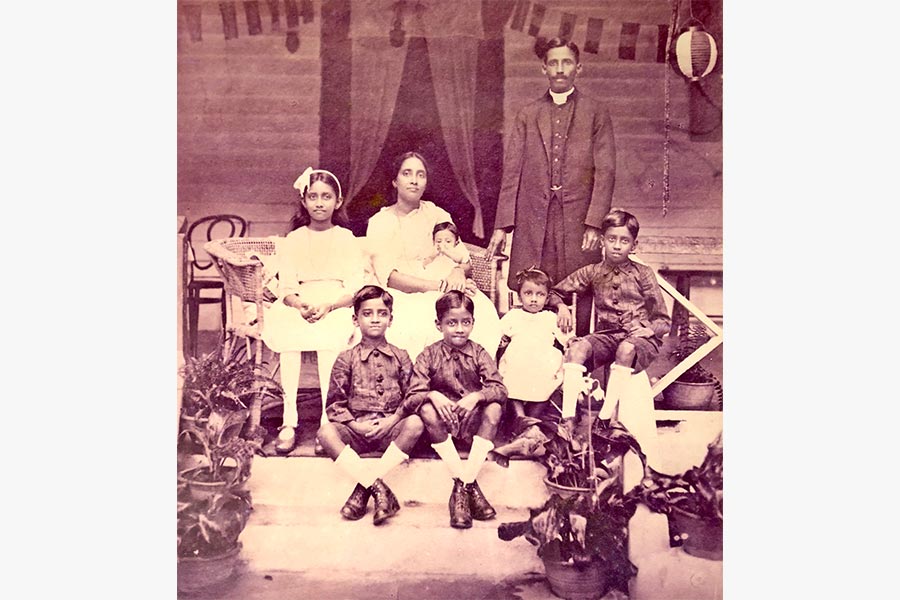

Annamalai Pillai’s nephew, Rev JA Supramaniam, married Harriet Navamani Joseph, whose lineage traced back to 13th century Jaffna royalty. Their son Dr JMJ Supramaniam was a pioneer in the management and elimination of tuberculosis in Singapore, and his son, Paul Supramaniam, has recorded his family tree showing five generations of his family in Singapore, and tracing their lineage to Kulasekara Singai Aryan Pararajasekaran Arya Chakravarty, King of Jaffna (1246-56 CE).

From Mannargudi to Singapore: The Ramasamy Family

P Ramasamy and his wife Rengammal arrived in Singapore in 1886 from Thirumakottai in Mannargudi, Tamil Nadu. They belonged to a community known as the Agamudyar Thevars who were landowners. On their arrival, Ramasamy joined the Straits Settlements Police Force and soon rose to the rank of Sergeant. The couple had four children Vaithinathen, Angammal, Muthia, and Manikam. Angammal married her relative Kuppusamy, a cattle trader.

Kuppusamy and his younger sister Ponnammal jointly owned a thaan or shed with stables for cattle and horse carts at Rochor. The horse carts were primarily rented out for the use of guests at the nearby Raffles Hotel. Ponnammal was also an industrious female entrepreneur who ran a lucrative kootu or tontine business in Rochor. Lakshmi, the daughter of Angammal and Kuppusamy, was trained in classical music by her illustrious musician aunt Amballigay who had come to Singapore in 1933 as the fourteen-year old bride of Manikam. The first public performance by Amballigay’s musical troupe took place in May 1937 at Farrer Park when Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter Indra made a short visit to Singapore and Malaya.

Lakshmi later married Rengasamy, the son of Kuala Lumpur’s wealthy Tamil merchant RM Davar, and the brother of the Indian National Army veteran Janaki Athi Nahappan. Lakshmi Rengasamy Davar was an educator and philanthropist who made charitable contributions to several Hindu temples and the Ramakrishna Mission.

The Ramasamy family trace their lineage in Singapore to six generations.

They came from Jaffna: The Family of Eliyathamby

Jaffna (Yazhpanam in Tamil) is located in northern Sri Lanka (Ceylon in the past). Tamils from this region included descendants of the old Tamil kingdom of Jaffna, the Vannimais or descendants of chieftains. Most of the early Tamils from Sri Lanka arrived as colonial personnel to Malaya and Singapore.

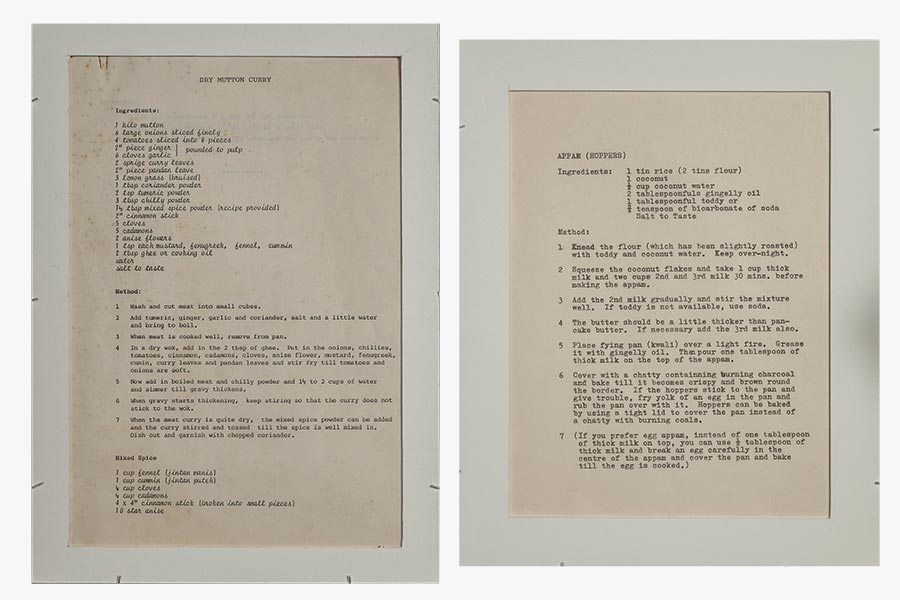

Born in Changanai, a market town in Jaffna, Eliyathamby worked as an assistant overseer for the British in Malaya. In this role, Eliyathamby supervised labour who cleared and built the roads that connected important towns. Eliyathamby’s grandfather Venasithamby and father, Muthuthamby had migrated from Jaffna to Malaya in the 1850s. They owned rice fields in Malaya and conducted trade with Jaffna. Eliyathamby subsequently married a relative Meenachi, from Chulipuram.

Both Meenachi and Eliyathamby belonged to a community known as Vellalar and hailed from a line of chieftains. Meenachi and Eliyathamby travelled to Malaya in the 1890s by a sailboat, and their descendants eventually settled in Singapore. Meenachi was a skilled culinarian , and brought with her cooking implements such as grinding stones, a wooden mortar and pestle as well as heirloom brass vessels that were passed through the generations.

Venasithamby and his descendants have been in Malaya and Singapore for seven generations.

Tamil Women

Family accounts and oral historical sources have informed us that Tamil women have been in Singapore from the second half of the 19th century. As labour, as convicts, as wives, and as entrepreneurs Tamil women were diverse in the walks of life they occupied in Singapore. Alamayloo Pillay arrived from Mauritius with her father Sabapathy Pillai in the second half of the 19th century and in 1890, she married Koona Vayloo Pillay. Madam Ponnammal was a private financier with operations at Rochor in the late 19th century. These are but two names of Tamil women who were 19th century personas in Singapore. What of the others who remain anonymous? This section serves as a reminder of the stories of many Tamil women that remain obscure, waiting to be discovered.

The story of the female Tamil migrant is often shrouded in anonymity and little is known of the lives of early Tamil female migrants to Singapore and Malaya. In response to this gender-imbalance, Anurendra Jegadeva attempts to recreate the journey of a contemporary diasporic Tamil girl by using his daughter as the central figure for this installation titled Heart in Hand.

The installation juxtaposes her Western oriented values against her ethno-cultural background inherited from her grandmother. The work further conveys the disconnect, even indifference felt by the children of migrants as they assimilate and negotiate their way through the same issues of identity and place, albeit twice removed, that was experienced by their grandparents.

The central panel of the altar presents Anurendra’s daughter, and she is surrounded by paraphernalia of the migrant including cooking implements, a famous migrant ship, auspicious birds, and ancestral portraits. The six wings of the altar, inspired by a thali, are hinged to the main panel. Embellished on back and front, each wing contains miniature paintings that contribute to the narrative of contradiction.

The middle boxes within these hinged wings house light-boxes with reproductions of Migrant Letters, works that incorporate letters from migrants. On the top of the panel, is a gopuram (temple tower-like crown) that houses another light-box depicting an electric guitar-playing Saraswati, the goddess of learning.

Duality and Diversity: The Family of B Govindasamy Chettiar

In the 19th century, residents in the Madras Presidency were conversant in Tamil, regardless of their own linguistic backgrounds. Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam were spoken across the Presidency, and residents were receptive to these diverse influences in culture and tradition. Consequently, migrants who arrived from the Madras Presidency, while predominantly Tamil, included those who were well versed in both Tamil and their own cultural and linguistic practices.

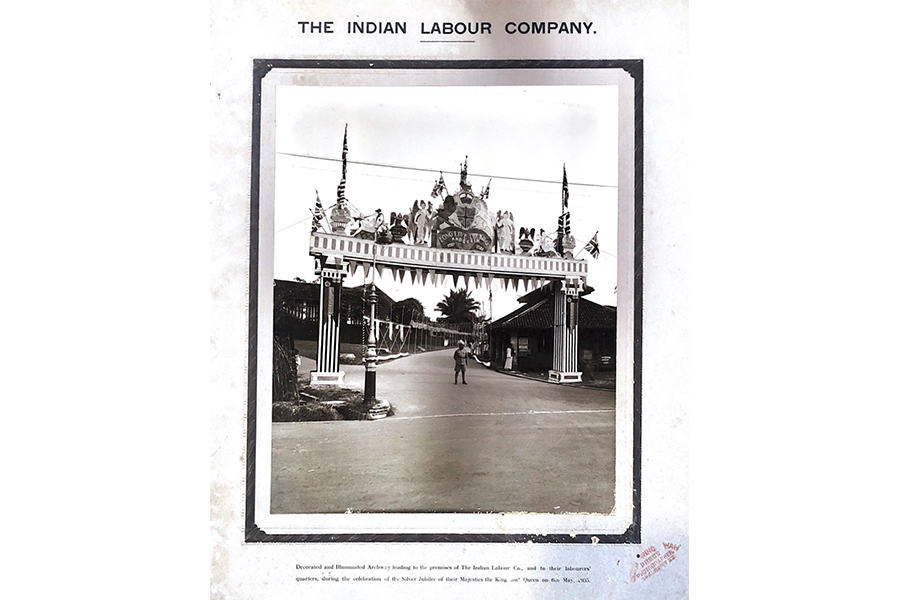

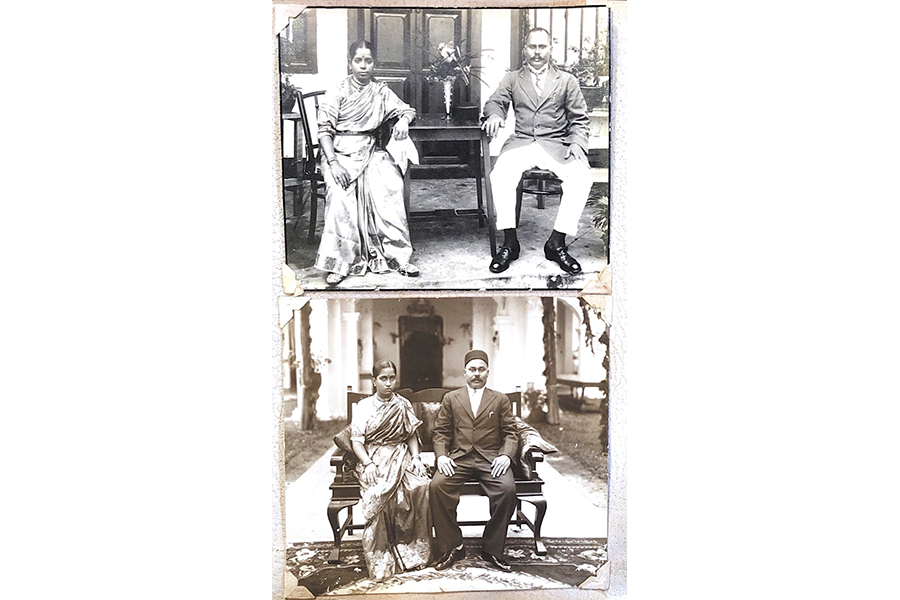

One such example was B Govindasamy Chettiar who arrived in Singapore at the turn of the century. He was proprietor of the Indian Labour Company and supplied the harbour board with wharf and dockyard workers. B Govindasamy’s offices and the labour quarters were located along Keppel Road. He was well known for distributing free meals at his shed to port workers and to members of the community which earned him the moniker Kottai Govindasamy. After a short illness, he died on 6 April 1948 at the age of 59 and his funeral attracted attendees from all races. Throughout the 1940s, B Govindasamy Chettiar was involved in the management of Vadapathirakaliamman Temple, and after his death, his nephew SL Perumal oversaw major renovations and the temple’s expansion in the 1970s.

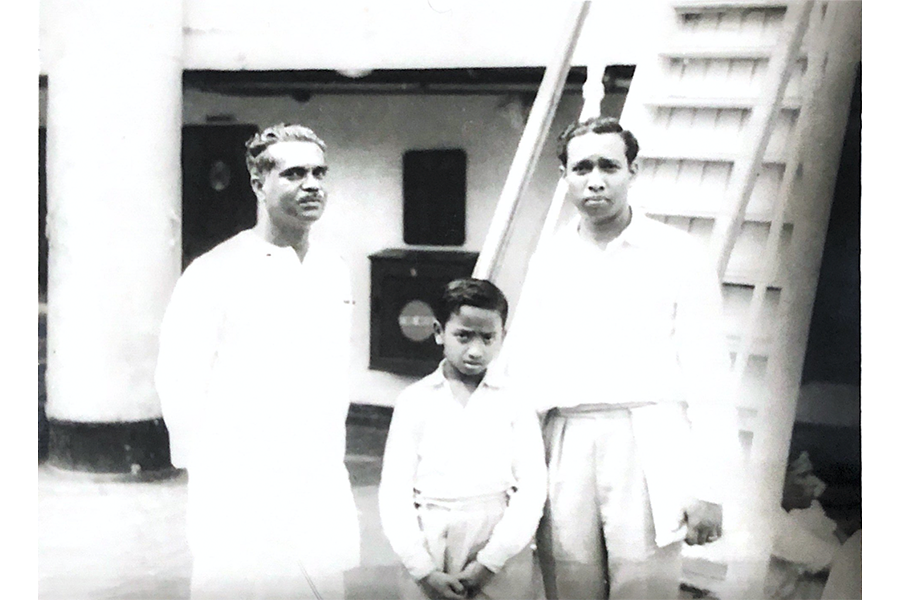

Journey Across the Seas: The Adhynamilagi Family

When looking at Tamil heritage in early Singapore, it is important to remember that a large Tamil mercantile community had long been present in Malacca, Penang, Myanmar, Medan, and Vietnam. The mobility of these traders, influenced the pattern of migration undertaken by Tamil diasporas. The descendants of Adhyakonar, an agriculturalist in the village of Mahibalanpatti in Sivagangai District, Tamil Nadu are one such example. Staunch followers of the patron guardian deity Adhynamilagi Ayyanar at Maruthangudi near Pillayarpatti. Narayanan father of Adhynamilagi and his uncle Mangaipahan both travelled via Nagapattinam to Southeast Asia.

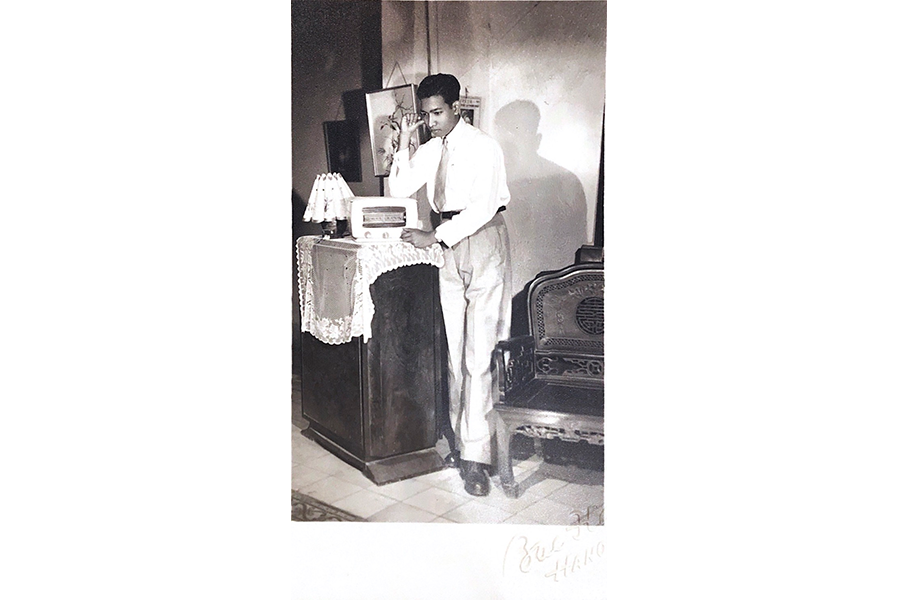

Mangaipahan established himself as a successful textile trader at the turn of the century in Saigon and Hanoi and was a patron of the Sri Mariamman temple there. Adhynamilagi boarded a ship from Nagapattinam and sailed for Singapore, and then joined his uncle in Vietnam to help him in his textile business. He returned to Singapore in the mid-20th century and worked as a clerk with the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company. Adhynamilagi was English-educated and multilinguist, lived in Market Street. Later brought his son to Singapore with him, while his wife lived in India and visited occasionally. In his later years, by the 1970s, he became a guide for Japanese tourists visiting Singapore. The family of Adhynamilagi can trace their roots back to 4 generations in Southeast Asia.

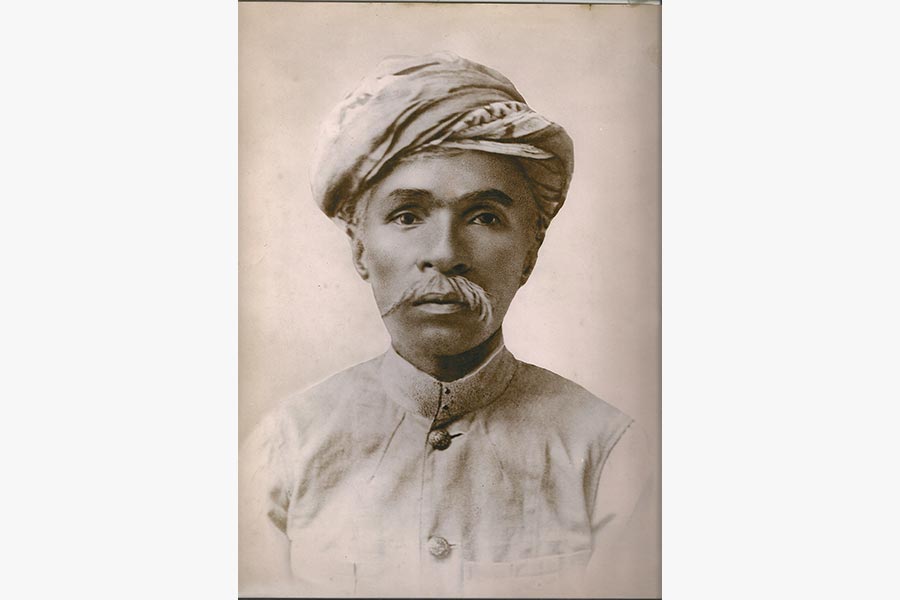

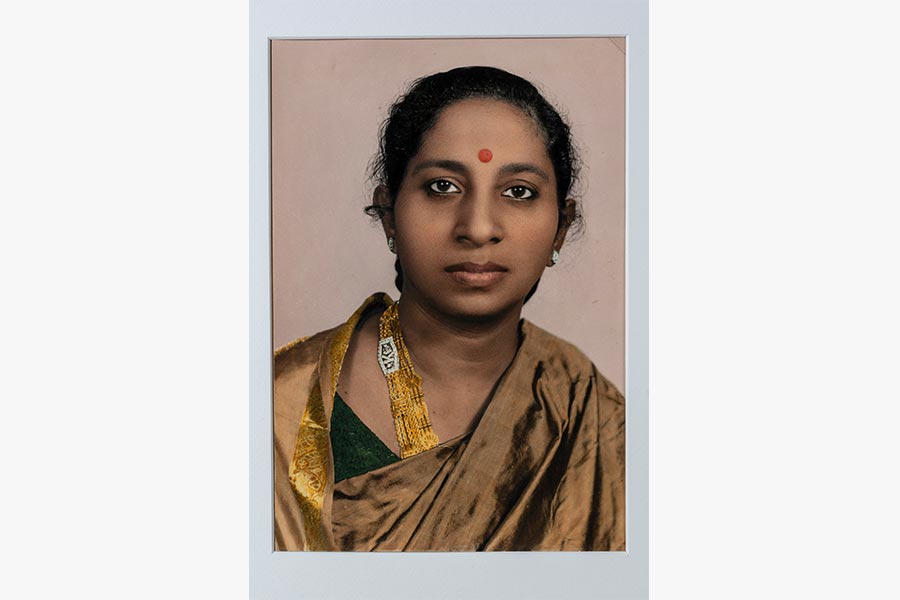

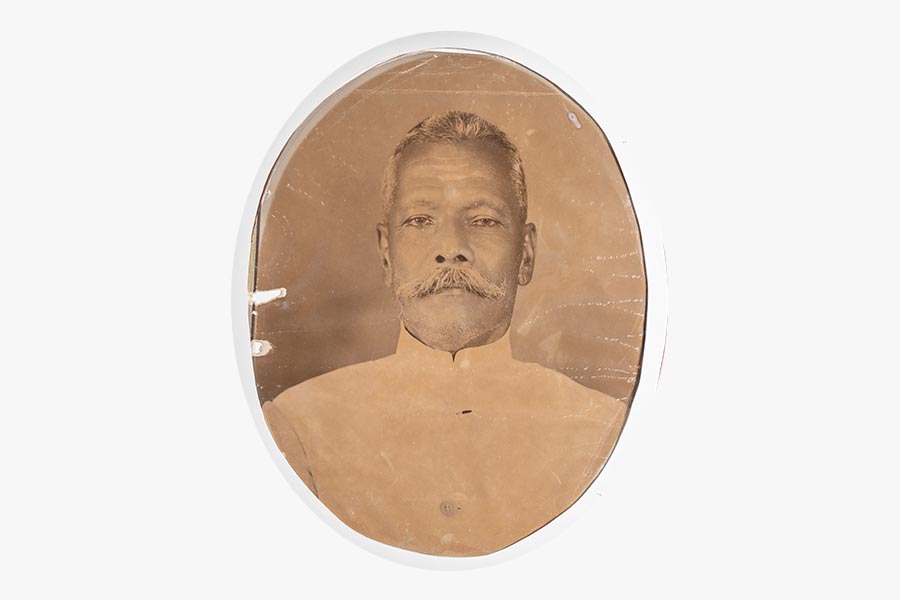

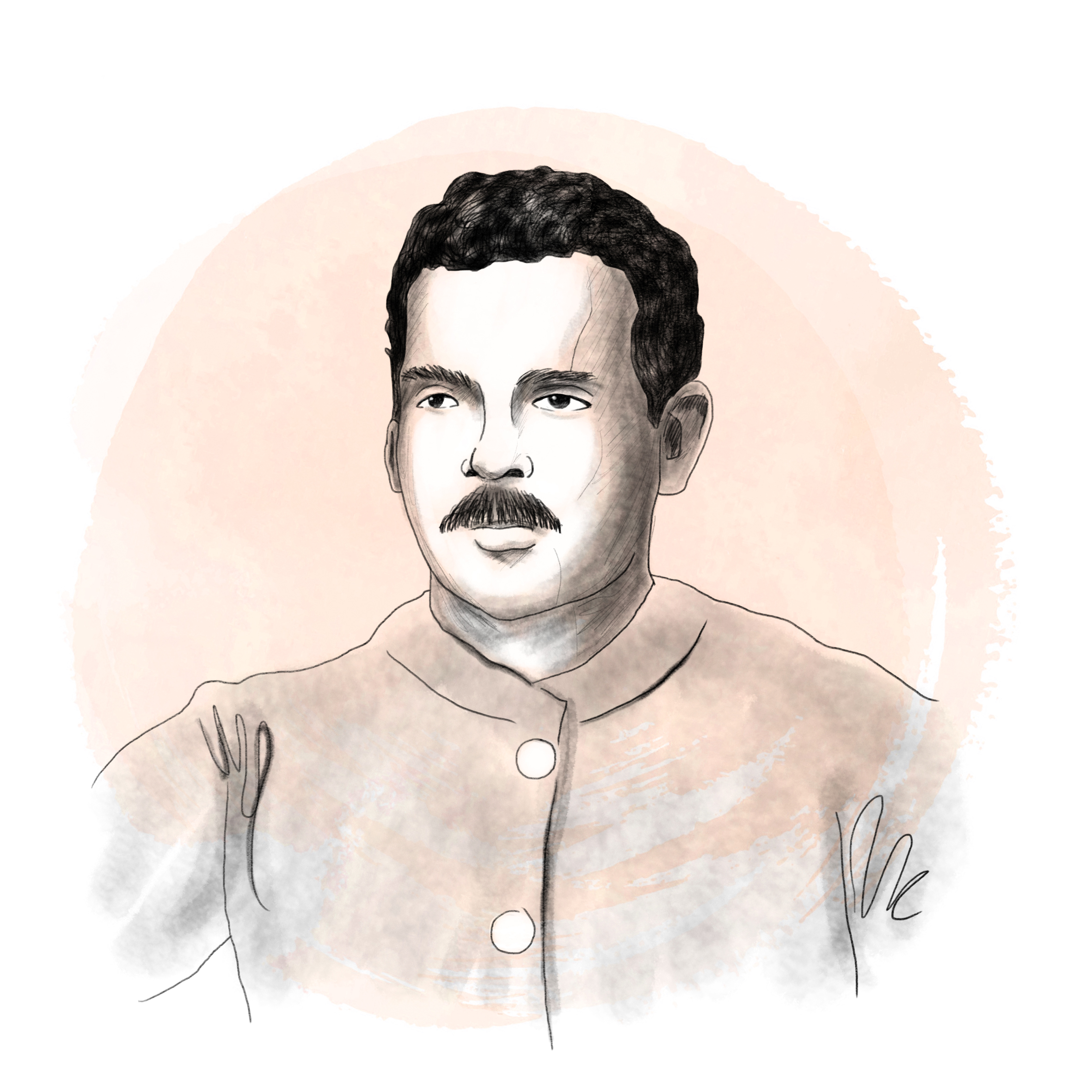

Portraiture

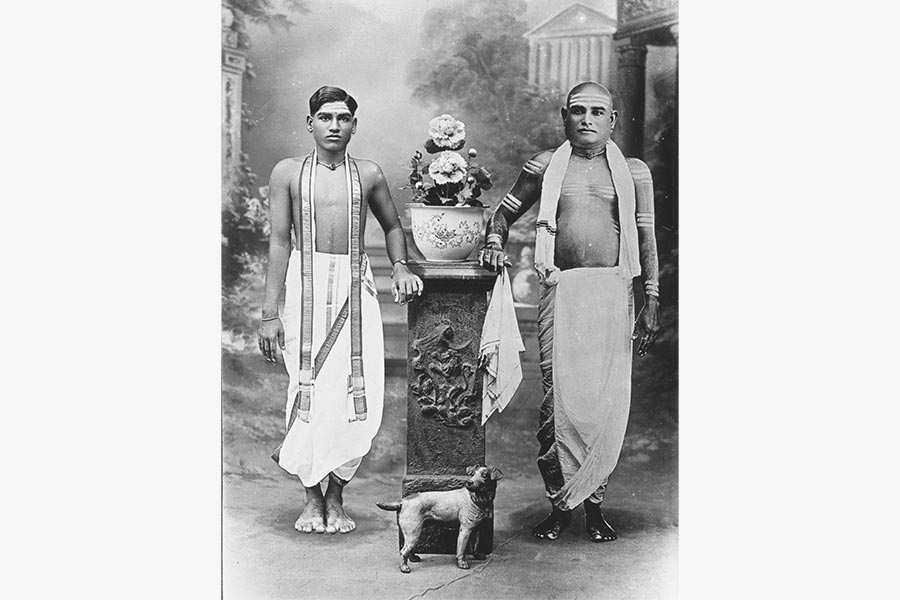

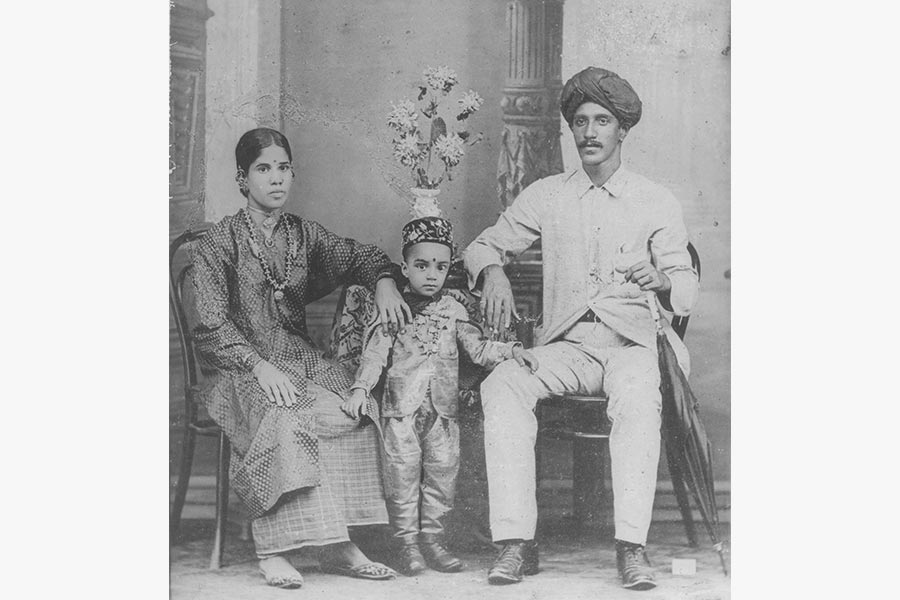

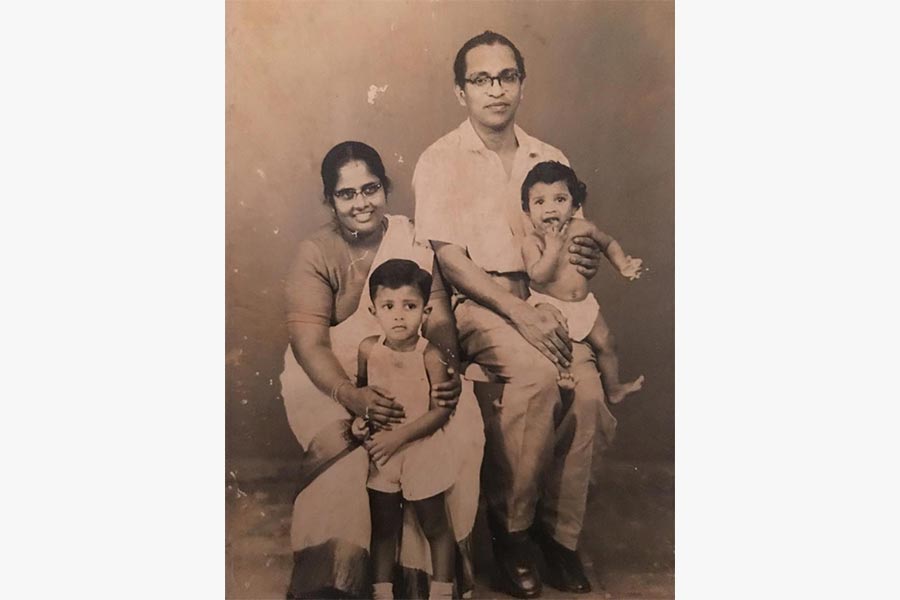

European curiosity over Asian diversity is manifest in the emergence of portraiture and photography by the 19th century in Singapore. The commodification and exotification of Indian culture for western audiences was also achieved through the medium of photography. A Sachtler of Sachtler & Co and John Thomson of Thomson Bro shot some of the earliest portraits of Indians in Singapore between the 1860s and the 1870s. Later, the firm of GR Lambert & Co, which operated from 1877 until the end of the First World War, produced the single most important collection of images of Singapore in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

These carefully curated photographs capture people from diverse trades and professions ranging from hawkers to labour; the exotic fashion of matriarchal women; and the family as a unit. Photographs such as these, together with those of other migrants, reinforced the exotic and mysterious image of Singapore. However, it is unfortunate that the names of these profiles were never documented, and they remain anonymous to date. To reverse the colonial neglect surrounding these studies are portraits of Tamil pioneers from the 19th and early 20th centuries identified in family collections and/or commissioned for this exhibition.

Revisiting the Past

Tamils in Singapore are a unique diaspora who have settled in the country, through continuous waves of migration, over a period of 200 years. It is evident that the roots of most present-day Tamil culture, customs, religious ideologies and affiliations in Singapore can be traced to the 19th century and that they have continued to evolve over the centuries. In fact, Tamil identity today is the product of a long history of traditional practices which have combined and incorporated local influences over time.

As early migrants became settlers, language and literature became useful tools that fostered social integration amongst the diverse groups of Tamils. Tamil language education was provided as early as 1834 in Singapore, and Anglo-Tamil schools were established in 1873 and 1876 to teach English through the use of Tamil. Today, Tamil is one of the four official languages of Singapore, and community and state-led efforts in the preservation and promotion of Tamil language continue unabated.

This exhibition traces the long history of Tamils in Singapore and highlights the stories of Tamil pioneers who played integral roles in the development of early Singapore. Since then, the Tamil community has continued to evolve, and the Singaporean Tamils of today are a vibrant and diverse community. They constitute an estimated 5% of Singapore’s population and yet continue to play an important role in shaping Singapore’s future.