TL;DR

In late-nineteenth-century Singapore, philosophers Lim Boon Keng and Tan Teck Soon represented contrasting positions: Lim embraced scientific materialism while Tan advocated idealism. Their debates on Chinese identity, religion, and culture exemplified early Singapore's navigation between Eastern and Western traditions.

On 30th March 1894, The Daily Advertiser reported that a heated debate had erupted in Singapore—one that revealed the fault-lines of a community caught between worlds. At the Chinese Christian Debating Society, a young Chinese doctor who had just returned from Britain stood before an increasingly agitated audience and declared that the Straits-born Chinese had failed to advance beyond their ancestors. The crowd was reportedly upset not just because of his provocative thesis, but also because of their unfamiliarity with the adversarial format of European debates.

The moment captures something profound about the intellectual ferment in Singapore at the turn of the century, where a remarkable generation of Straits Chinese thinkers grappled with fundamental questions of knowledge, identity, and human flourishing. Among them, two figures stand out for the sophistication of their engagements: the young doctor himself, Lim Boon Keng, as well as the older editor of The Daily Advertiser, Tan Teck Soon.

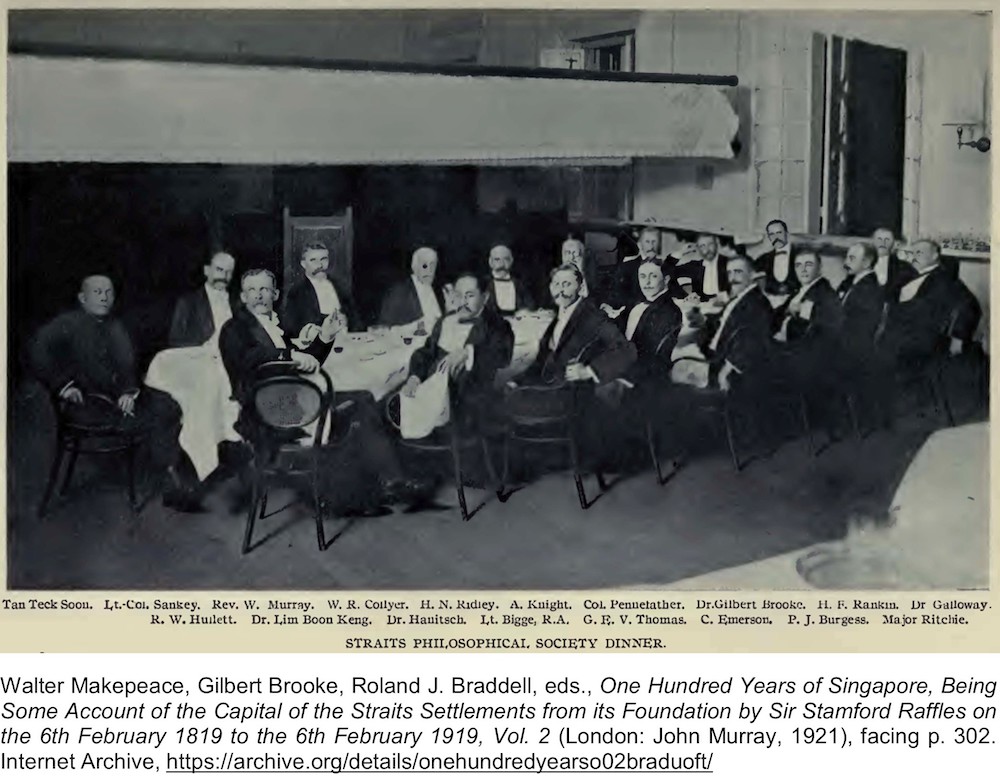

A year after the debate, Lim joined the Straits Philosophical Society which Tan had co-founded, and the two would become the only non-European resident members throughout the society’s history. Their intellectual partnership and divergences alike offer a fascinating window into how early Singapore negotiated modernity on its own terms.

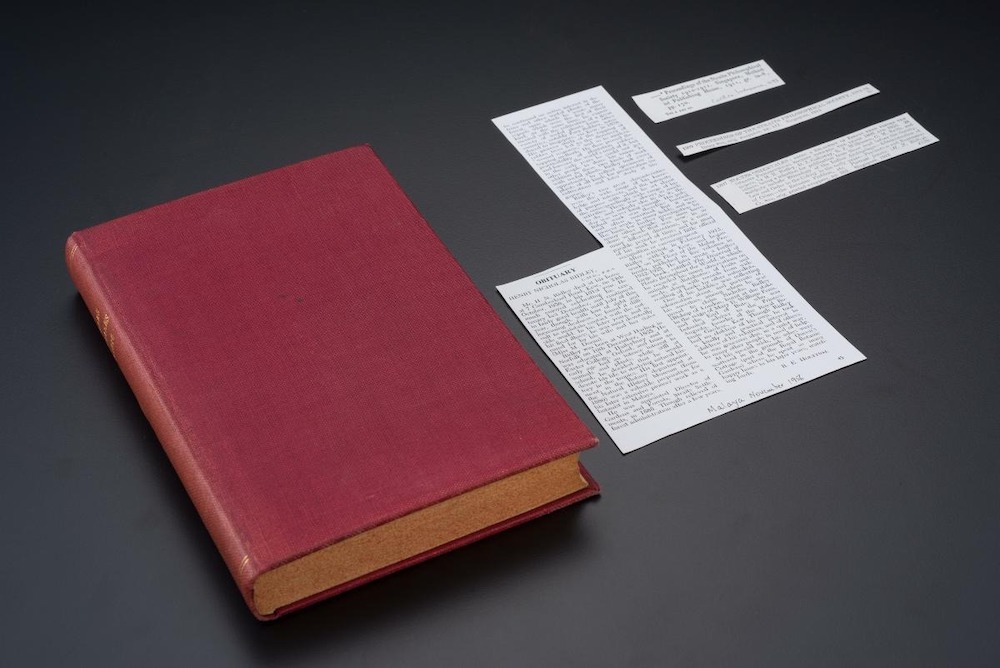

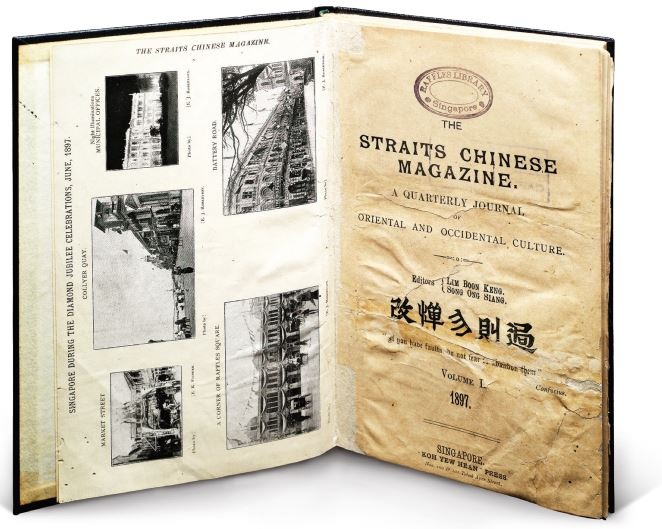

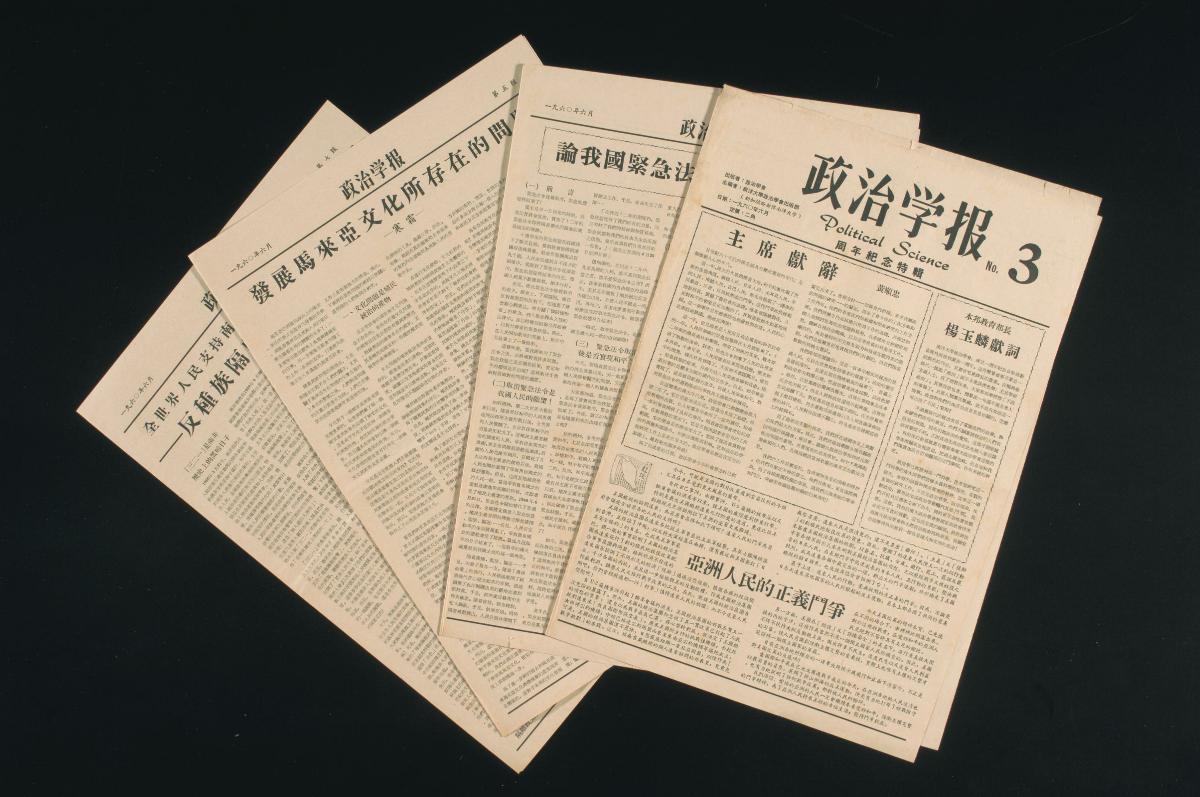

A century before Singapore’s first philosophy department, these men were already engaged in serious inquiry through institutions like the Straits Philosophical Society and publications like the Straits Chinese Magazine. Their discussions, though now forgotten, revolved around fundamental questions that philosophers have long wrestled with: Why are humans social beings? How do we come to acquire our racial and cultural identities? What is the relationship of precise scientific knowledge to a holistic understanding of our place in the world?

The Materialist and Idealist

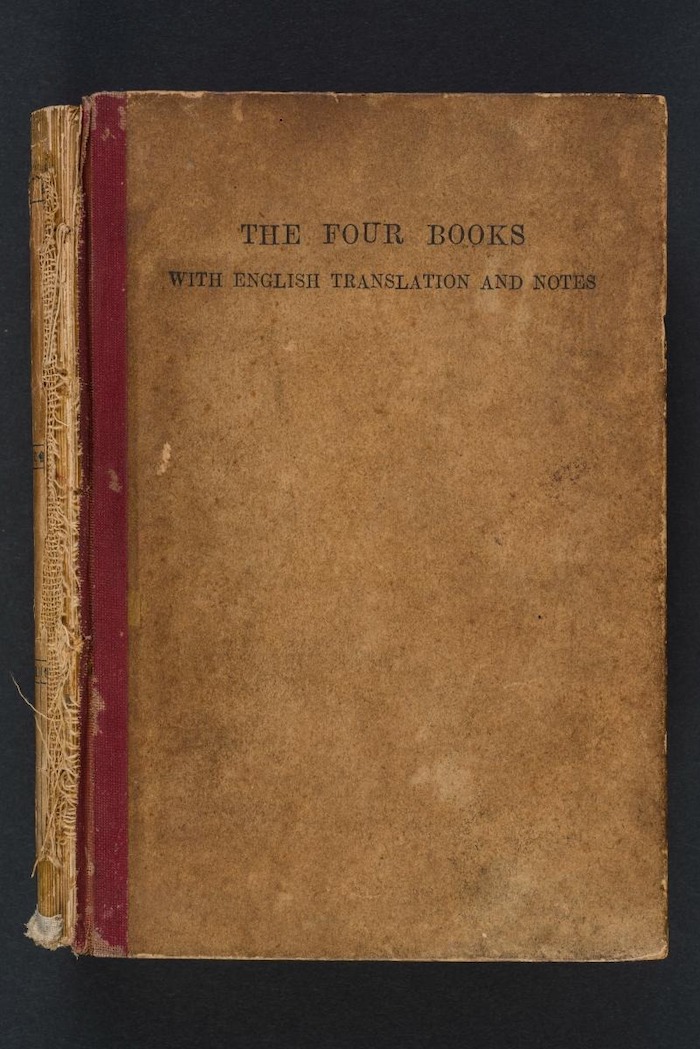

Lim, educated at Edinburgh and Cambridge in the late nineteenth century, embraced what might be called scientific materialism. For him, philosophical inquiry was primarily a matter of scientific investigation suited to the modern mind. In one essay, writing under the pseudonym ‘Wen Ching,’ he argued against the existence of a soul based on its redundancy in explaining human behaviour—a position not unfamiliar to philosophers of mind today. Prefiguring leading philosophers in China of his time, Lim saw a kinship between scientific and Confucian approaches to human nature, reinterpreting the Classics through the lens of the burgeoning evolutionary sciences developing in Britain.

Tan fundamentally diverged from Lim. The former developed a sophisticated critique of scientific reductionism that anticipated the phenomenological insights of the later twentieth century. “The task of science is to render thoughts (that is, the representation of things) concise and exact,” he wrote, “but all our thinking is done by concentrating our attention upon a definite point.” This creates artificial boundaries that “do not exist in nature” but are “the artifice by which we are enabled to grasp the thing.” The danger, Tan warned, lay in forgetting “what belongs to our method and what to objective reality”—mistaking “our formulas to be the real things.[1] Tan, not restricting himself to Confucianism either, developed his position from intellectual forebears hailing from German Idealist, Buddhist, and Daoist philosophies.

But this was not merely an abstract disagreement. It shaped how each of them understood human social existence itself. For Lim, following Thomas Huxley’s definition of anthropology as “a section of zoology,” human beings were fundamentally social beings due to the evolutionary need for interdependent survival and flourishing.[2] Meanwhile, Tan, in developing his idealism, saw human sociality as emerging from the social nature of the ideals guiding our lives. These are drawn from the wider community’s collective pool of ideals, with each individual act of thinking contributing to its continual development.

‘Orang Cina Bukan Cina’?

Both men faced an acute personal and philosophical puzzle: what constituted ‘Chineseness’ for those like themselves? As exemplars of colonial education in the early days of Raffles Institution—Lim graduating with a Queen’s Scholarship, Tan earlier with a Guthrie Scholarship—they were highly articulate in English and steeped in Anglo-European thought. Lim was a member of the Peranakan Chinese community, whose ‘Chineseness’ was often questioned in early Singapore. Tan was the first son of an influential Hokkien Christian missionary—Tan See Boo, who had left his family in Amoy upon conversion—as well as an English-educated orphan—Yeo Geok Neo. Neither Lim nor Tan, unlike many other Chinese in Singapore then, had close familial ties to China. Further, both had been engaged with Anglo-American Christian communities as youths. In the absence of conventional ties, how then could either lay philosophically justifiable claims to Chinese identity?

Lim’s answer was systematic: ‘Chineseness’ was constituted by language, culture, and religion. In a public lecture, he declared that “in order to appreciate Chinese classics and ideals one ought to know and read Chinese,” though he pragmatically accepted that the threshold didn’t require extensive command.[3] He understood that proper cultural assimilation, when done on the basis of scientific progress, need not entail a fundamental alteration of one’s own culture—hence his calls to ban the towchang, or queues, for reasons of hygiene and modern standing.

Given Tan’s metaphysical commitments, he was sceptical of Lim’s relatively neat categorisations. While less optimistic about widespread literacy among Singapore’s predominantly labouring Chinese population, Tan noted that knowledge of any language was proportional to the degree of democratic support available to a government. His position on cultural assimilation resembled that of contemporaneous Bengali philosopher Krishna Chandra Bhattacharyya, who argued that foreign cultural ideas must be “translated into our own indigenous concepts” before acceptance or rejection based on whether they expressed deeper truths of our own forms of life.[4]

On religion, the differences were particularly striking. Lim, encouraged by his encounter with Qing reformist Kang Youwei and his first sister-in-law Ruth Hwang, a Confucian-feminist novelist, saw Confucianism as a universal religion grounded in scientific materialism. Lim’s renovation of Confucianism, as a scientific religion for the modern Chinese, galvanised a revival throughout Southeast Asia and even back in China, during his 16-year presidency at Amoy University.

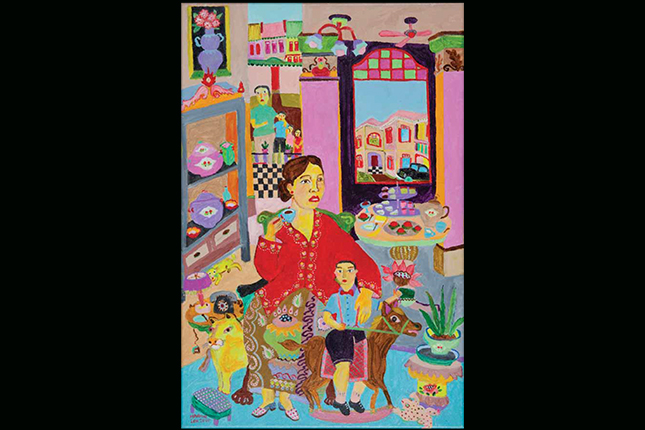

Tan took a more pluralistic approach. “Universality may be the ultimate aim of all positive religions,” he wrote, “but each civilization must evolve its own means to arrive at such universality out of its own life-impulses and resources.5As the Singapore representative of the Maha-Bodhi Society, founded by the Sri Lankan Buddhist revivalist Angarika Dharmapala, Tan urged for greater understanding of Buddhism among the Straits Chinese while still acknowledging Confucianism’s importance. In a syncretic spirit akin to that depicted in traditional paintings of the Three Vinegar Tasters, Tan saw religious development occurring through constant dialogues between Confucian ideals and other religions—Daoism, Buddhism, even Christianity and Islam.

Impressions and Expressions

Their philosophical differences extended to art, revealing how deeply their commitments shaped their entire worldview. For Lim, artistic creation and appreciation involved “a faculty in the brain concerned with the perception of harmony, and of beauty”—a scientific approach that led him to argue that artworks were “more or less the faithful incarnation of the authors’ ideals.” But these ideals could only aid human beings in realizing their “higher destiny”—the ability to “move in unison with the spiritual rhythm of the universe”—if they fit one’s language, culture, and religion.[6]

This led Lim to some striking aesthetic judgments. In his 1927 novel The Tragedies of Eastern Life, Lim’s narrator criticized wealthy Straits Chinese who employed German architects despite their differing sensibilities, describing one mansion as “an utter fiasco” that was “huge and vulgar” as well as “bizarre and grotesque.” Even when these architects “were worshipped by every one as the greatest of the white races,” Lim insisted that aesthetic ideals must be culturally appropriate to be beautiful and meaningful.[7]

Tan’s idealist aesthetics led him in precisely the opposite direction. Much Chinese art, he argued, suffered from “a monotonous sameness” and “a want of individuality” indicative of “mechanical” rules that allowed “no liberty for the free exercise of the imagination.[8] This he attributed to a tendency towards an “inability to hold ideas apart from their concrete embodiment,[9] stemming from the dominance of “only one school of thought, the Confucian,” which Tan characterises as materialistic.[10]

Tan found hope for developing an artistic Straits Chinese spirit in “appreciative studies” of “scenes and views unfamiliar with their daily surrounding and unusual to their ordinary conceptions […] whether native or foreign.[11] Aesthetic taste should seek out unfamiliar perspectives and cultural expressions in everyday life, developing what we might call a transcendental sensibility. This was to be found not only in the classics but also more modern and popular forms of art. Through this, one could discover new ideals necessary for a community to grow and adapt.

From Community to Nation and Beyond

Most remarkably, despite their frequent collaborations and philosophical differences, no record has been found of how Lim and Tan thought about each other’s positions. Their intellectual partnership seems to have been sustained by a generous disagreement that allowed profound philosophical differences to coexist with practical cooperation. What emerges is a picture of two sophisticated thinkers engaged in fundamental dialogues about knowledge, identity, and human flourishing. Their debates were not just academic—they shaped community institutions, educational approaches, and cultural practices that influenced generations of Straits Chinese. Lim and Tan’s efforts became beacon lights for our founders to launch an independent nation amidst the fog of decolonisation and the Cold War.

As Singapore turns 60 this year, the 130-year-old philosophical legacy of Lim and Tan deserves recognition, not just as historical curiosity, but as an inherited legacy. Their example suggests that philosophical cosmopolitanism—thinking across cultural boundaries while cultivating one’s own particularities—emerges from the lived experiences of people navigating often rough waters between cultural contact zones. In their willingness to engage seriously with scientific materialism and idealism, Confucian ethics and Buddhist spirituality, local traditions and global currents of thought, Lim and Tan embodied the open vision we still need to navigate the ever-changing tides of our world today.

Lilith Lee is an assistant professor in history of philosophy at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam in the Netherlands and was a 2024 National Museum of Singapore Research Fellow. She is currently working on an academic monograph, Medical Confucianism: The Straits Chinese Philosophy and Politics of Lim Boon Keng (co-authored), as well as a popular anthology, A Beacon Light to the Straits Chinese: Philosophical Writings of Tan Teck Soon.

Notes

[2] Thomas H. Huxley, Critiques and Addresses (London: Macmillan and Co., 1873), 135.

[3] Krishna Chandra Bhattacharyya, “Svaraj in Ideas” [1928–1930], Indian Philosophical Quarterly 11:4 (1984): 393.

[4] “The Chinese Language.” Malaya Tribune, 13 June 1919.

[5] Tan Teck Soon, Criticism of “Mohammedanism” by W.G. Shellabear [1915], Proceedings of the Straits Philosophical Society for the Year 1915–1916 (Singapore: Methodist Publishing House, 1916), 46.

[6] Lim Boon Keng, “The Influence of Art on Civilization” [1913], The Great War from the Confucian Point of View and Kindred Topics: Being Lectures Delivered during 1914–1917 (Singapore: The Straits Albion Press, 1917), 33–34.

[7] Lim Boon Keng, The Tragedies of Eastern Life: An Introduction to the Problems of Social Psychology (Shanghai: The Commercial Press, 1927), 8–9.

[8] Tan Teck Soon, “Chinese Art,” Straits Chinese Magazine 4:16 (1900): 167.

[9] Tan Teck Soon, “The Chinese View of Cremation” [1893], Transactions of the Straits Philosophical Society 1 (1894): 47.

[10] Tan Teck Soon, “Some Genuine Chinese Authors” [First Paper], Straits Chinese Magazine 1:2 (1897): 64. 11 Tan Teck Soon, “Chinese Art,” 174.

[11] Tan Teck Soon, “Chinese Art,” 174.