TL;DR

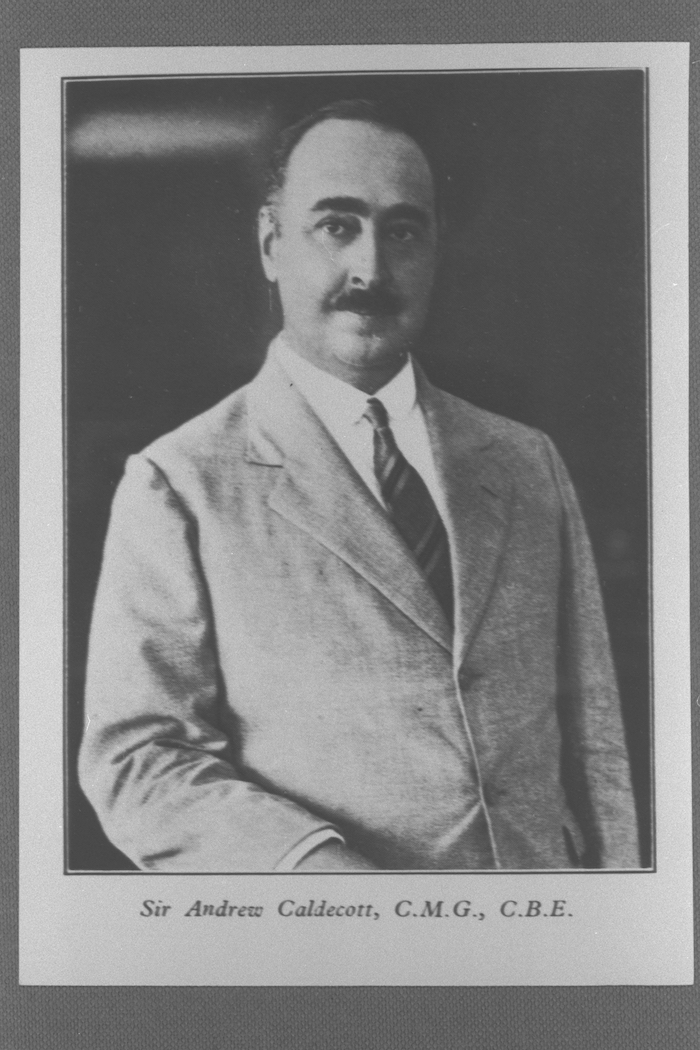

For over eight decades, Caldecott Hill served as Singapore's broadcasting nucleus. Named in 1937 after colonial administrator Sir Andrew Caldecott, the site evolved from the British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation to become MediaCorp, witnessing and broadcasting the nation's pivotal moments. From introducing colour television in 1974 to launching iconic local productions and discovering homegrown talents through Star Search, the hill remained Singapore's premier media hub until its relocation to one-north in 2015, leaving behind a rich legacy of programmes that shaped the national consciousness.When Sir Andrew Caldecott joined the Colonial Service in 1907, aged twenty-three and fresh out of Exeter College, Oxford, he would never have imagined that his name would forever be synonymous with Singapore’s broadcasting history. Starting as a cadet in Negeri Sembilan, the young administrator worked his way up through the ranks, serving as Acting District Officer (DO) in Jelebu and Kuala Pilah before reaching the position of Colonial Secretary for the Straits Settlements in 1934. Well-loved and known for his adept skill at dispute resolution, Caldecott also served as the 1st President of the Football Association of Malaya.[1]

In 1937, Andrew Caldecott left Singapore for Hong Kong where he served as Governor. In his honour, the government named a little hillock off Thomson Road after him – Caldecott Hill – and named the surrounding roads after his wife Joan and children Olive and John.[2] Around the same time that Singapore’s first broadcast facilities were being built on Caldecott Hill, a new cluster of housing was being developed around them. Comprising “nearly seventy houses in a hundred acres of land,” its developer touted it as having “one unique feature – modern sanitation.[3]

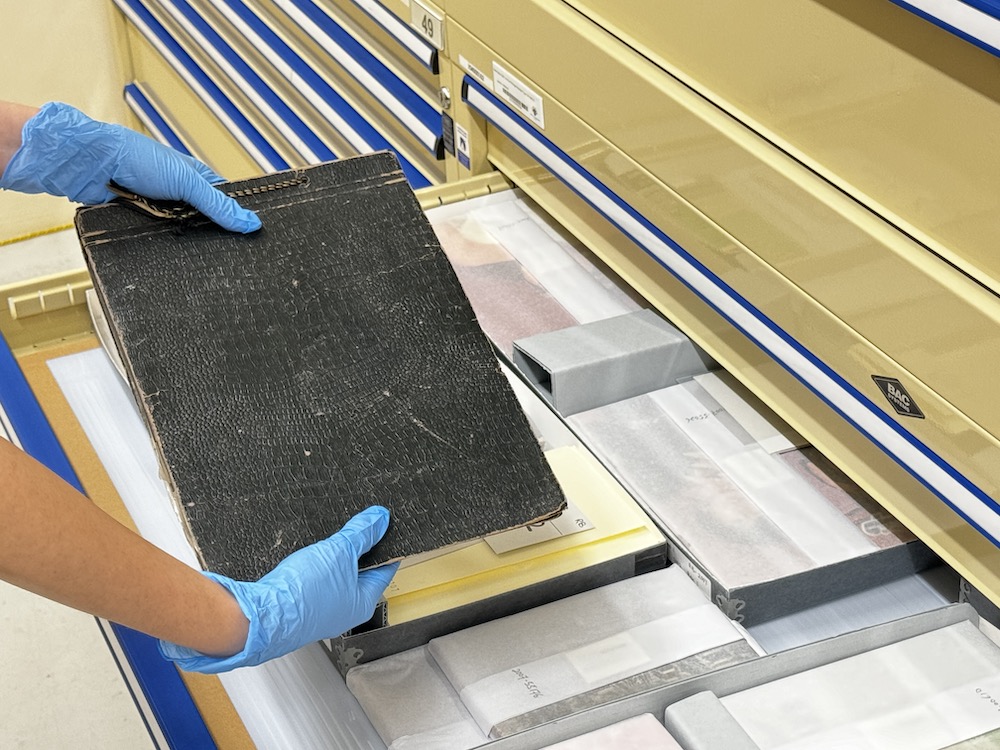

In 2023, Mediacorp teamed up with the National Heritage Board to tell the story of Caldecott Hill in “A History of Singapore’s Broadcasting: Behind the Scenes of 80 Years at Caldecott.[4] This 45-minute documentary traced the evolution of Singapore’s radio and television industry, interweaving national milestones and personal stories. Through interviews and archival footage, viewers got to see how this historic hill shaped Singapore’s media landscape, revealing its textured and lively history.

From informing Malaya to informing Malaysia (1935 – 1963)

Singapore’s broadcasting journey began in April 1935 with a private company - the British Malaya Broadcasting Corporation (BMBC).[5] At its peak, BMBC, which began test transmissions in January 1937, broadcast in eight languages on medium wave for thirty-six hours a week.[6] Despite this impressive reach, it remained unprofitable and in 1940, the colonial government bought it out for $275,000, took control of the airwaves and reconstituted it as the Malayan Broadcasting Corporation (MBC), with Eric Davis as Director-General of Broadcasting.[7]

When Singapore fell to the Japanese on 15 February 1942, they quickly seized MBC’s facilities and relaunched it as Radio Shonan in March 1942.[8] Broadcasting from transmitters at Caldecott Hill, the station mainly relayed programmes from Radio Tokyo, along with local news and music. The Japanese occupation of the airwaves lasted until September 1945. After Japan’s surrender, the British quickly reclaimed the station. Listeners heard a voice, greeting them in English, “Good afternoon, this is Southeast Asia Command Headquarters broadcasting from Singapore.[9] The war was over.

Post-war, radio was handed back to civilian management in April 1946 with the end of the British Military Administration (BMA). A new entity - Radio Malaya, Singapore and the Federation of Malaya (RMSFOM), commonly known as Radio Malaya was to provide news and other broadcasts. The station found a permanent home in 1951, when Radio Malaya moved to its new $484,000 headquarters at Caldecott Hill.[10] After the Federation of Malaya gained independence in 1957, it was renamed Radio Singapore – an independent entity – and in 1959, designated as Singapore’s public broadcaster.[11]

Even before Singapore joined Malaysia, the People’s Action Party (PAP) government recognised how radio could be used to reach the people. Arun Mahiznan , formerly a senior producer at Radio Television Singapore (RTS), the post-1965 successor to Radio Malaya, recalls that the government saw it as “a very powerful tool, to not only just inform” but also persuade. For him, one radio programme in particular demonstrated this power of persuasion – the twelve radio broadcasts entitled “The Battle for Merger ”, delivered by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew from 13 September 1961.[12] These broadcasts aimed at exposing the real motives of those who opposed Singapore’s merger with the Federation of Malaya. To reach the widest possible audience, these speeches were broadcast three times a week in multiple languages across various platforms, including radio.[13]

During Singapore’s brief union with Malaysia from 1963 to 1965, the station operated as Radio Malaysia’s Singapore branch.[14] When Singapore became independent on 9 August 1965, the station was reorganised as part of Radio Television Singapore, operating under the Ministry of Culture.[15]

From Radio Television Singapore to Singapore Broadcasting Corporation (1965 – 1980)

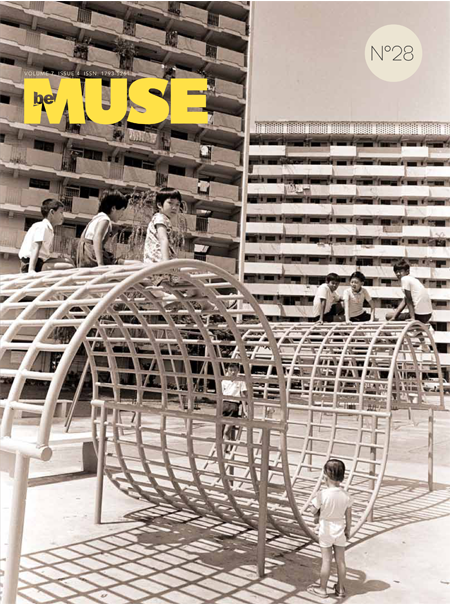

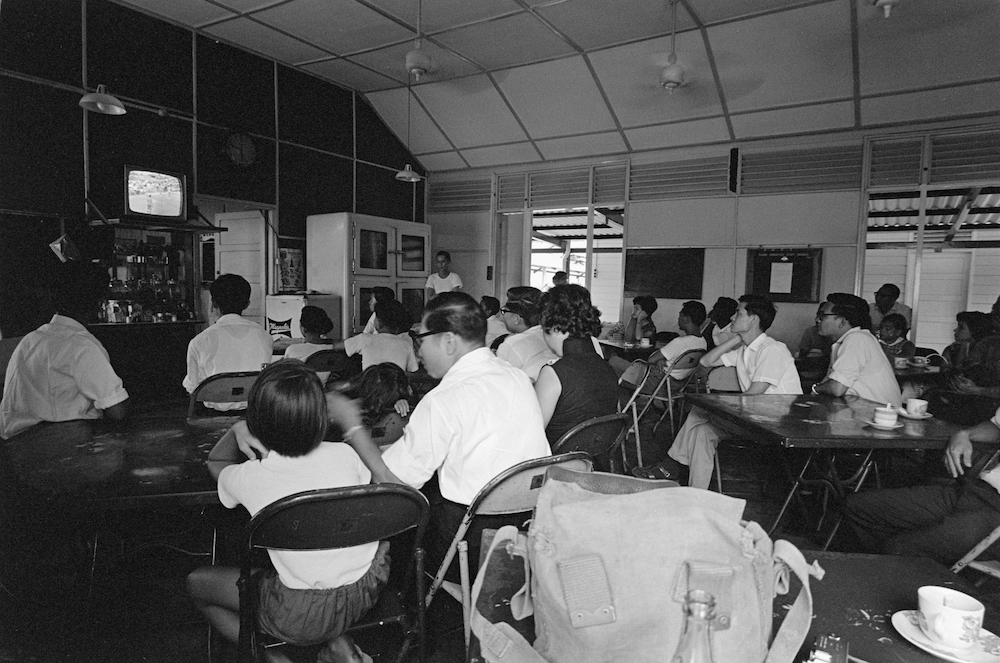

In May 1960, the government announced plans to introduce television to Singapore.[16] As with radio, a television unit was set up in the Ministry of Culture.[17] Television Singapura was launched less than three years later, on February 15, 1963, with 300 guests gathering at Victoria Memorial Hall for its inaugural broadcast. Though grainy black and white footage, it marked the beginning of a new era in mass communications in Singapore. Mun Chor Seng, a media veteran with forty years’ experience, recalls that watching television was a novelty and a communal activity.[18] For many Singaporeans of that generation, crowding around a neighbour’s television set became a part of their collective memory.

Few moments in our nation’s history match the significance of Singapore’s separation from Malaysia on 9 August 1965. Thanks to television producer S. Chandra Mohan’s snap decision, this historical moment was captured for posterity. He recalls,

Instinctively, I just told the camera to zoom in, I said hold the shot at the face ,and tears started streaming down his face. He could not continue. And he said, “do you mind if we stop for a while?” Then I faded the picture to black.[19]

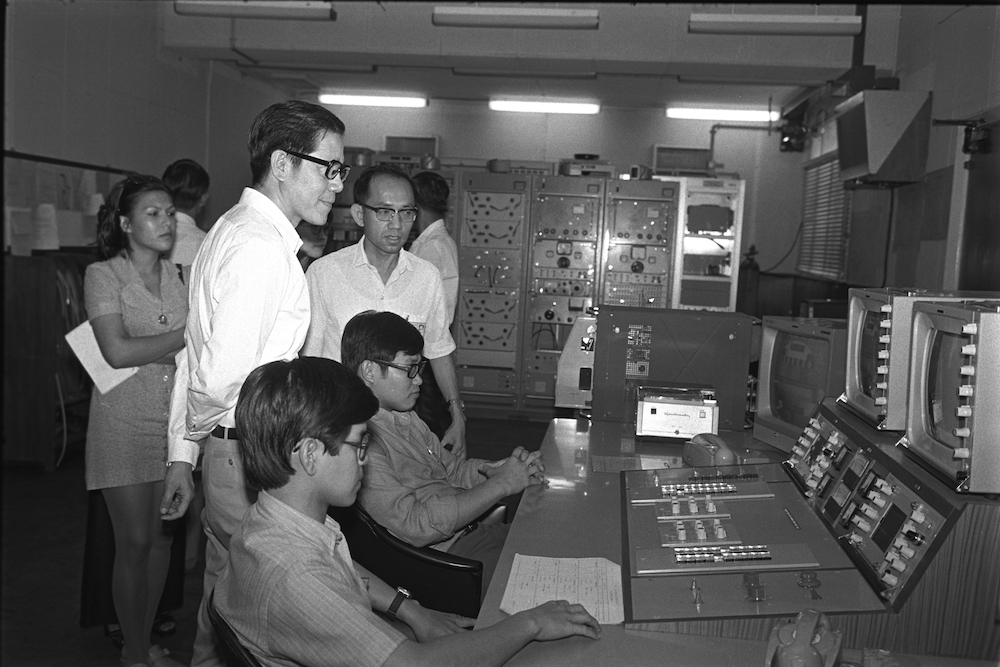

After independence, Television Singapura merged with Radio Singapura to form Radio Television Singapore (RTS).[20] The new broadcaster took on an important role in nation-building, and through its programming, entertained, educated and informed Singaporeans. To support this mission, a new $3.6 million Television Studio Centre opened on Caldecott Hill in August 1966.[21] RTS continued to grow, adding a $10 million earth satellite station at Sentosa in 1971.[22] Likewise, in 1974, colour television, dubbed “a gamechanger of an upgrade,” made a splash with RTS’ first “live” colour television broadcast of the 1974 FIFA World Cup football finals between West Germany and the Netherlands.[23] The box, once black and white, now showed the world in its full splendour, in colour.

In 1976, RTS launched a talent competition that would capture Singapore’s imagination - RTS Talentime. Susan Ng, who became the show’s face in 1978 at age 21, looks back at its impact,

It was our “American Idol” at the time. It was popular because it was live, and you are rooting for one particular person… it’s giving hope to regular people who might not have the opportunity to be talent scouted on the streets of Singapore.[24]

A new chapter in Singapore's broadcasting history began in 1980 when Parliament passed the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation Act. This transformed RTS into the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation (SBC), a statutory board with greater operational flexibility and the ability to respond more quickly to audience needs. The change positioned SBC to better serve Singapore's growing and increasingly sophisticated viewership. The new organisation marked this fresh beginning with a distinctive logo - a golden videotape flowing against a blue background. [25]

Serving Singapore Slices of Life (1980 – 1994)

Looking back, the 1980s marked the "Golden Age" of television in Singapore. As a statutory board, SBC was well-positioned to expand its creative horizons and develop ambitious original content. The organisation could now tap into international expertise, bringing in experienced professionals to complement local talent and enhance Singapore's broadcasting capabilities[26]

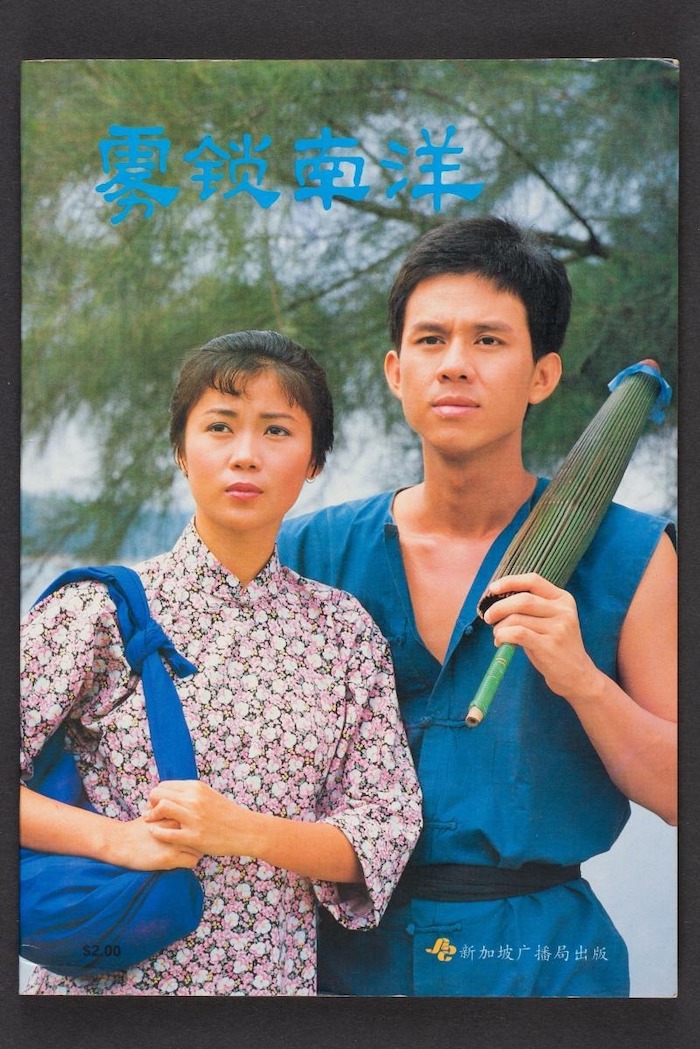

One of these professionals was Chan Bang Yuan, who moved to Singapore in 1983, as part of a team of Hong Kong televisional professionals. Their task? To start up SBC’s Chinese drama division. Their first production was The Awakening , a historical drama trilogy that captivated a generation. Starring homegrown stars Huang Wenyong and Xiang Yun as Ah Shui and Ah Mei, the drama was set in Singapore’s history, from its early days, through the Japanese Occupation and its struggle for independence. Both Huang and Xiang Yun became household names and local television drama soon gained its own faithful following.

There were, however, stumbling blocks. Singapore simply did not have enough actors and actresses. As Chan put it, “It is (sic) not a big pool of talent…so we start (sic) our long journey of growing this talent pool.[27] Similarly, there was a dearth of facilities, but this did not deter them. A backlot was quickly built on Caldecott Hill and this was used until the purpose-built Tuas TV World was opened a decade later in 1993.[28]

At the same time, a concerted effort was made to build up local expertise. Newsroom production crew were posted to the Chinese drama division to cut their teeth. They were exposed to the ins and outs of managing a production team, directing actors, all through observing and studying their foreign counterparts.[29] However, local knowledge was still needed to supplement international experience, especially in ensuring authenticity in the second season of The Awakening. Choo Lian Liang, a Chinese current affairs producer, remembers, “for example, we don’t say that we go picking durians with a basket. You don’t climb a tree to pick durians, you have to wait for them to fall.[30]

Singaporeans soon “grew hungry for local content.[31] There was a need for stars, instant ones, who could attract and captivate local viewers. To do so, Star Search, a talent hunt, was launched in 1988. Contestant No. 5, 20-year-old Zoe Tay, emerged champion and began her long reign as Queen of Caldecott Hill.[32] However, behind the glitz and glamour, Tay found acting life gruelling. She recalls working 363 days out of 365 days a year, a schedule that she remembers as “quite crazy.[33] In the 1990s, Tay and her Star Search cohort, Aileen Tan and Chen Hanwei, to name but a few, became household names and veteran actors in their own right.[34] For SBC, the Star Search franchise effectively became a pipeline for talent to be discovered and parachuted into the industry, providing a growing pool of actors and actresses as it expanded its Chinese drama offerings. The talent pool problem that Chan alluded to earlier was solved.

The Next Lap (1994 – 2015)

In 1994, SBC was privatised and rebranded as Singapore International Media (SIM) Group, which had three entities – the Television Corporation of Singapore (TCS), the Radio Corporation of Singapore (RCS) and Singapore Television Twelve. As a private body owned by Temasek Holdings, SIM Group retained its responsibilities as a national broadcaster[35]

1994 also saw Singapore’s first foray – more than a decade after the Chinese drama division produced The Awakening – into English television drama. The first attempt, Masters of the Sea, created by noted American television producer Joanne Brough, struggled to connect with local viewers.[36] Media industry veteran Ng Say Yong explains why: “People can’t relate to people coming in on a hot Singapore day wearing a sweater and speaking with a clipped accent, so there was that disconnect with the audience.[37] This was a valuable lesson – viewers wanted authentic stories they could truly relate to.

This connection was made by Under One Roof, released later that year. This sitcom, starring Moses Lim as Tan Ah Teck and Koh Chieng Mun as Dolly, struck a chord with viewers by portraying everyday life in a Bishan HDB flat. Another hit followed with Growing Up, a nostalgic drama set in post-independence Singapore that captured hearts with its portrayal of simpler times. The next year, in 1997, a loveable Singlish-speaking contractor named Phua Chu Kang became an instant hit in an eponymous sitcom, spawning the catchphrases, “don’t pray pray (sic)” and “best in Singapore and JB, and some say even Batam.” Phua Chu Kang, as portrayed by actor Gurmit Singh, would go on to become a national icon. Singapore’s English television drama had found its winning formula: authentic local stories, told in our own voice. When a viral respiratory disease, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) hit Singapore in early 2003, Phua Chu Kang joined the public health campaign, delivering important messages through his catchy rap, “SARS is a virus that I just want to minus, no more surprises, if you use your blain use your blain!” It was a perfect example of how Singapore used local humour to communicate serious messages effectively.[38]

Channel News Asia went on air on 1 March 1999 to offer audiences an Asian perspective on global events as an alternative to international networks like CNN. For the anchor launching the inaugural broadcast, the experience was unforgettable, “I was the luckiest guy on earth to be there on the right day at the right time.[39] Behind the scenes, the team faced technical challenges, particularly with the new virtual background technology. Studio director Sandy Lam remembers, “there was lot of testing…because this is the first time we’re using a green screen…no one is supposed to wear anything that is green colour or any green element in it.[40] In June 1999, SIM became the Media Corporation of Singapore – MediaCorp, and underwent restructuring to meet changing market demands, including launching a new sports channel.[41] [42] [43] In 2019, Channel News Asia was rebranded as CNA to reflect its “transmedia multiplatform identity.[44]

The Year of Two Farewells

2015 marked two significant farewells for Caldecott Hill. The first came on 23 March 2015, when Mediacorp mobilised to cover the biggest event since independence, the death of founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. On March 29, more than 100,000 Singaporeans lined the streets to pay their last respects and salute the man during the state funeral procession. Millions more watched the broadcast live on television and online. It was a sombre, grey and rainy day. Interviewees waited patiently while camera crews wiped the raindrops off their lenses. Low Tian Ling, who worked at Caldecott Broadcast Centre for 39 years, recalls that there was a power trip at one broadcast location. They had no choice but to improvise and use a nearby resident’s power supply to ensure that the coverage could continue uninterrupted. The hiccup went unnoticed, thanks to the dedication and ingenuity of the outdoor broadcast crew[45]

In December 2015, Mediacorp began its nine-month migration from Caldecott Hill to its new premises at one-north. The move was the culmination of a long farewell first announced in December 2010.[46] Caldecott Broadcast Centre’s facilities, ageing and occasionally ramshackle, belied what its people imagined it to be. It was “a window to the world,” a “magic kingdom,” where “dreams are being made”. Veteran cameraman Dekarajen Sanmugam wistfully shares that, “I came in as a bachelor, I got married, I became a father and then I become a grandfather…it gave me my life, a complete life.[47] Mun Chor Seng would drive up to the hill “even though it’s no longer around… just to remember this is the area that keep (sic) me alive.[48]

A Legacy That Lives On

For generations, Caldecott Hill’s broadcasts were a portal into a world of glitz and glamour for Singaporeans. These stories form our collective memory, allowing us to share both historic events in Singapore’s history and everyday joys. Through the radio broadcasts and television programmes it transmitted, Caldecott Hill reached deeply into every Singaporean household and left an indelible imprint on successive generations through these shared experiences.

Watch A History of Singapore Broadcasting: Behind The Scenes Of 80 Years At Caldecott here.

This article was contributed by the Built Heritage team of the National Heritage Board.

Notes

[2] “Caldecott Through The Years”, National Heritage Board, last accessed on 28 May 2025, https://www.roots.gov.sg/stories-landing/stories/Caldecott-Through-the-Years/story

[3] “Colony Cavalcade,” Straits Times, 7 Feb 1937, 2.

[4] “A History of Singapore Broadcasting: Behind the Scenes Of 80 Years at Caldecott”, CNA Insider, last accessed on 28 May 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bEgiy6xvkXc.

[5] (NHB research) “Singapore Broadcasting Station”, Straits Times, 21 Feb 1937, 9. “The B.M.B.C”, Straits Times, 15 Jan 1940, 8.

[6] (NHB research) “Opening by Governor this evening”, Straits Times, 1 March 1937, 12.

[7] ‘Government and BMBC’ Straits Times, 2 Mar 1940, 10; and ‘BMBC Shareholder Complains of Unfair Treatment by Government’ Straits Times, 3 Mar 1940, 7; (NHB research) “Malaya to Broadcast to Entire Far East”, Straits Times, 3 June 1941, 11.

[8] (NHB research) “It Seems to Me”, Singapore Free Press, 21 Apr 1949, 4..

[9] “On Air: Untold Stories from Caldecott Hill” (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2019), 30 – 34.

[10] (NHB research) “Untitled”, Singapore Free Press, 5 November 1951, 1.

[11] “Radio Broadcasting in Singapore (1946–65)”, National Library Board, last accessed on 29 May 2025 https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=2b972ada-0a21-4bfd-841f-976693cdcaae .

[12] Mediacorp documentary (7:03 – 8:06); “Lee Kuan Yew delivers radio talks in the battle for merger”, National Library Board, last accessed 29 May 2025, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=f661e5e1-d5fa-4588-9360-e35fa457e98d .

[13] “Lee Kuan Yew delivers radio talks in the battle for merger”, National Library Board, last accessed 29 May 2025, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=f661e5e1-d5fa-4588-9360-e35fa457e98d .

[14] “Radio Broadcasting in Singapore (1946–65)”, National Library Board, last accessed on 29 May 2025 https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=2b972ada-0a21-4bfd-841f-976693cdcaae .

[15] “Radio Broadcasting in Singapore (1946–65)”, National Library Board, last accessed on 29 May 2025 https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=2b972ada-0a21-4bfd-841f-976693cdcaae .

[16] “Singapore TV: ‘It’s Definite”, Straits Times, 30 May 1960, 9.

[17] (NHB Research) “How Television Came to Singapore”, Straits Times, 1 March 1963, 2.

[18] Mediacorp documentary (8:08 – 9:31).

[19] Mediacorp documentary (10:19 – 10:59).

[20] https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=f84fe603-7339-4629-b781-50b75fa3d21f 21 (NHB Research) “New Home for TV”, Straits Times, 27 Aug 1966, 10.

[22] “Singapore Joins Select Space Coms Club”, Straits Times, 24 Oct 1971, 18.

[23] Mediacorp Documentary, (16:59 – 17:20).

[24] Mediacorp Documentary (17:26 – 18:18).

[25] “SBC Act is approved”, The Straits Times, 12 January 1980, 1; https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19800112-1.2.6?qt=singapore,% 20broadcasting,%20corporation,%20act&q=singapore%20broadcasting%20corporation%20act%20 ST 2 Jan 1980, 3 & 12 Jan 1980, 1; “Singapore Broadcasting Corporation is established”, National Library Board, last accessed on 28 May 2025, https://www.nlb.gov.sg/main/article-detail?cmsuuid=19fe790d-ffda-49ed-a925-ec237e7dda6e .

[26] Mediacorp Documentary (18:25 – 19:13).

[27] Mediacorp documentary (19:47 – 19:53).

[28] Mediacorp documentary (19:50 – 20:34); “Tuas Television World”, Remember Singapore, last accessed on 29 May 2025, https://remembersingapore.org/tuas-television-world/.

[29] Mediacorp documentary (21:16 – 21:40).

[30] Mediacorp documentary (21:05 – 21:12).

[31] Mediacorp documentary (21:30 – 21:32).

[32] Mediacorp documentary (23:39 – 24:01).

[33] Mediacorp documentary (24:38 – 24:45).

[34] Chen Han Wei, Mediacorp, last accessed 29 May 2025, https://www.mediacorp.sg/business/tca/male-celebs/chen-han-wei-12357548; Aileen Tan, Mediacorp, last accessed 29 May 2025, https://www.mediacorp.sg/business/tca/female-celebs/aileen-tan-12357704 .

[35] “Singapore Broadcasting Corporation”, National Archives of Singapore, last accessed 29 May 2025, https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/government_records/agency-details/172#:~:text=On%201%20 October%201994%2C%20SBC%20was%20privatised,(TCS)%2C%20Radio%20Corporation%20of% 20Singapore%20and%20Singapore.

[36] “Joanne Brough, 77, Influential TV Executive, Is Dead”, New York Times, last accessed 29 May 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/15/arts/television/joanne-brough-77-influential-tv-executive-is-dead. html ; “Masters of the Sea”, TMDB, last accessed 29 May 2025, https://www.themoviedb.org/tv/21131-masters-of-the-sea.

[37] Mediacorp Documentary (27:09 – 27:35); “Ng Say Song”, IMDA, last accessed 28 May 2025, https://www.imda.gov.sg/about-imda/research-and-statistics/support-for-industry-sectors/media/film/dir ectors/ng-say-yong .

[38] Mediacorp Documentary (31:50 – 32:36).

[39] Mediacorp Documentary (29:03 – 29:36).

[40] Mediacorp Documentary (29:38 – 30:20).

[41] Teo Pau Lin, “SlMple change of name for media group” Straits Times, 16 June 1999, 3.

[42] Catherine Ong, “TCS parent Media Corp of S'pore restructures units” Business Times, 16 June 1999, 4.

[43] “New sports channel coming your way” Straits Times, 7 July 1999, 3.

[44] “CNA’s 25th anniversary: Mediacorp’s news network announces plans to scale up growth in regional and international markets”, Mediacorp, last accessed 28 May 2025, https://www.mediacorp.sg/media-releases/cnas-25th-anniversary-mediacorps-news-network-announc es-plans-scale-growth-regional-and-international-markets-186396.

[45] Mediacorp Documentary (40:03 – 41:29).

[46] MediaCorp to relocate to Mediapolis@one-north” Mediacorp, last accessed on 28 May 2025, https://www.mediacorp.sg/corporate/news-release/media-releases/mediacorp-to-relocate-to-mediapoli s-one--5856096 .

[47] Mediacorp Documentary (44:34 – 44:56).

[48] Mediacorp Documentary (44:14 – 44:31).