TL;DR

Singapore's shophouse "French Windows" challenge their European label. These unglazed, full-length windows with outward-opening wooden leaves were adapted for tropical climates, prioritizing ventilation over views. Emerging during the colonial period, they blend Western styles with local needs, sharing similarities with Malay Tingkap Labuh (‘long window’). This feature exemplifies Singapore's unique architectural identity, combining colonial influence and local adaptation.(Image Above) Full-length wooden shutters are prevalent in Singapore shophouses. (Courtesy of Xue Xuan.)

When admiring Singapore's historical shophouses, one cannot help but notice the intriguing full-length openings on the upper floors. This feature often prompts the question: "Are they doors or simply tall windows?" These door-like windows, consisting of two wooden leaves that open outwards, often mislead observers into thinking they provide direct access to the outside or into the shophouse itself.

These façade elements are formally termed "French windows," suggesting European origins. Given the colonial influence on Singapore’s built heritage and the prevalence of Western neo-classical terms in descriptions of our eclectic-style buildings, this label has been widely accepted without much scrutiny. The term has circulated extensively in both academic and non-academic publications, persisting in use today.

But what exactly is a French window? To understand this, we must look to Europe, where window development was intrinsically linked to the history of glassmaking.[1] While glazed windows date back to the Roman period,[2] craftspeople long struggled to produce large, highly transparent glass panes.[3] The process was labour-intensive and time-consuming, making glazed windows a luxury reserved for the wealthy.

It was not until the 16th century, with advancements in flat glass production, that glazed windows began replacing wooden shutters in many European buildings.[4] These windows met three crucial human needs—light, air, and views—offering advantages that wooden shutters simply could not match.[5]

As glazed windows evolved, different designs emerged to suit various climates and lifestyles. The French window, a full-length casement window hinged on one vertical side and opening from the middle, gained popularity in early 19th century Britain. This design appealed to those seeking a closer connection with the external environment, providing unobstructed views from inside the building. French windows could also serve as doors to porches or terraces, allowing easy movement between indoor and outdoor spaces.

This evolution of the French window in Europe provides context for its appearance in Singapore's architectural landscape, bridging the gap between European design influence and local adaptation in Southeast Asian colonial architecture.

A typical French window at the Villa Carlotta. (Courtesy of Heng Chye Kiang.)

The Urban Redevelopment Authority’s conservation guidelines between 1988 and 1992 used the term "French window" to describe the "full-length, side-hung, double-shuttered windows found on the upper story facades of shophouses."[6] However, these windows in Singapore's shophouses differ significantly from their European counterparts.

Firstly, the long windows in Singapore shophouses are typically unglazed. In early Singapore, glazing was a premium imported commodity, appearing only in a few landmark buildings or those owned by the affluent.[7] Wooden panels or shutters were more popular due to their cost-effectiveness and accessibility. More importantly, opaque wooden shutters better addressed concerns about overheated interiors, reducing direct light and facilitating airflow. Ensuring interior thermal comfort is the primary function of full-length fenestrations in Singapore’s shophouses. The two wooden leaves, hinged to the vertical sides, can be fully opened to provide maximum airflow.

Despite being door-length, these windows do not provide access to a balcony or garden. Unlike true French windows, their wooden louvred leaves open outward, not inward, allowing space within the frame for a balustrade. All evidence suggests that these openings in Singapore’s shophouses are adaptations to the tropical climate, fundamentally distinct from the Western concept of French windows, which were designed to maximize views and provide access to outdoor spaces. This raises questions about the appropriateness of the term "French window" for these full-length openings in shophouses. If not French windows, what should they be called?

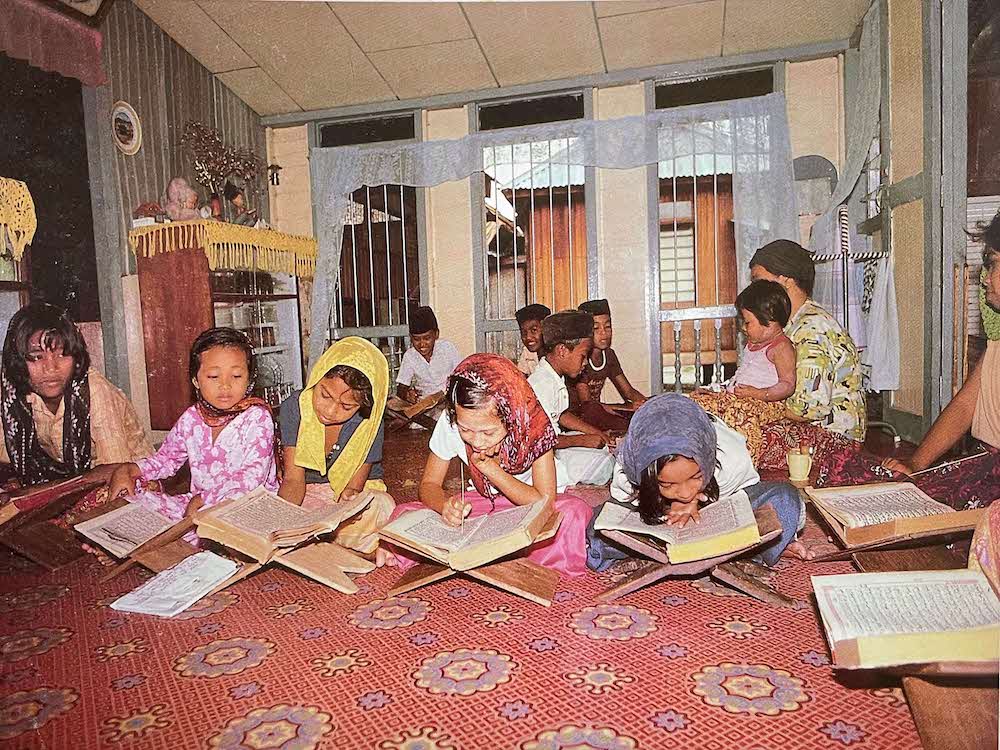

Looking elsewhere in Malaya, we observe similar full-length fenestration in the Tingkap Labuh (literally meaning "long window") of traditional Malay houses found throughout the peninsula.[8] These houses share material, form, and function with Singapore’s shophouses—wooden construction, of roughly body height, and primarily serving ventilation purposes. They also feature an innovative local design—the wooden leaves are cut at waist level, allowing homeowners to open the top half, bottom half, or both to accommodate changing conditions. In both building types, ornamental woodcarving with floral motifs often decorates the balustrade, headed transom, and window leaves, derived from Malay architectural traditions where carved panels typically decorate doorways and walls. This similarity prompts us to consider whether the fenestration in urban shophouses might actually have been inherited from traditional houses elsewhere in Malaya.

An examination of Singapore's 19th-century urban landscape reveals that floor-length window/door openings emerged with the earliest shophouses. Initially, these featured one or two square-headed windows with minimal ornamentation. Later, more elaborate façades appeared, with elongated windows and shutters in pairs or groups of three, often topped with fanlights and adorned with Palladian motifs, presenting a classical façade style.[9] These full-length shutters were also seen in many public buildings, including warehouses, offices, and civic structures. The proportion and regularity of the two long, narrow window leaves aligned with Palladian rationality, contributing to a townscape of classical order and harmony. Often, these windows were kept open throughout the day, providing a cooler interior environment for workers and occupants.

Early shophouses at Boat Quay in Alphonse-Eugène-Jules Itier’s daguerreotype. (1884, Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore.)

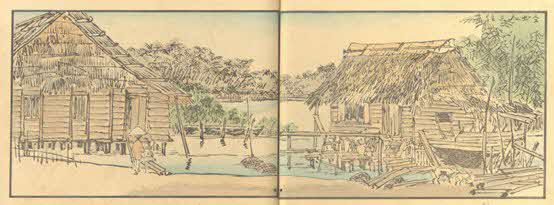

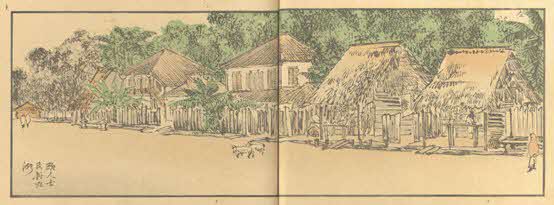

On the other hand, archival images from 19th-century Singapore show that elongated window openings were not initially present in vernacular Malay houses. Prints from Beisen's Travel Album 米僊漫遊画乘 depict 19th-century Singapore's Malay houses with very small window openings. In contrast, urban shophouses and suburban bungalows occupied by European settlers typically featured floor-length openings. As the artist Kubota Beisen noted, with the prejudice of his time: "European settlers' houses are grand and well-furnished while the indigenous people live in grass huts or thatched cottages with earthen floors, lying and rising amid the dust."[10]

(b). European dwelling houses, characterised by floor-length wooden shutters

(Courtesy of National University of Singapore Libraries.)

Abdul Halim Nasir and Wan Hashim’s examination of Malay houses in the broader Malayan region corroborates this observation. They argue that windows were gradually enlarged over time, with full-length fenestration appearing only in the later colonial period, during 19th-century British rule.[11] As traditional Malay houses had minimal interior partitions, these full-length windows facilitated cross-ventilation throughout the house, ensuring thermal comfort whether seated or standing.[12] This close relationship with the Malay way of living imbued full-length fenestration with vernacular cultural significance.

The evidence thus suggests that long windows in Singapore shophouses did not solely originate from the Tingkap Labuh of Malay houses, as earlier speculated. Rather, both forms emerged during colonial rule and were adapted over time to meet local natural and cultural needs.

Instead of using the term 'French window', we propose 'long window' or Tingkap Labuh, as these terms more accurately capture this design feature's functional purpose and cultural influence. Recognizing the local evolution of these windows also underscores their importance to Singapore's broader architectural heritage and unique identity.

This research was supported by the National Heritage Board’s Heritage Research Grant.

Notes

[2] The earliest glazed windows were found in excavations in Pompei. See Klos, “The Historic Development of the Window: From Its Origins through to the Early Modern Era,” 13; Konzo and Doyle, Speaking of Windows, 1.

[3] Konzo and Doyle, Speaking of Windows, 1.

[4] Hentie Louw, “The Development of the Window,” in Windows: History, Repair and Conservation, ed. Michael Tutton et al. (Dorset: Donhead Publishing, 2007), 7–96. 7

[5] Before glass was widely used, there were wooden shutters.

[6] Urban Redevelopment Authority, Historic Districts in the Central Area: A Manual for Little India Conservation Area (Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority, 1988); Urban Redevelopment Authority, Historic Districts in the Central Area: A Manual for Kampong Glam Conservation Area (Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority, 1988).

[7] Urban Redevelopment Authority, Conservation Technical Handbook : A Guide for Best Practices | Volume 5 | Doors and Windows (Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority, 2019), 23.

[8] Abdul Halim Nasir and Hashim Haji Wan Teh, The Traditional Malay House (Shah Alam: Penerbit Fajar Bakti Sdn. Bhd., 1996), 23.

[9] Julian Davison, Singapore Shophouse (Singapore: Talisman Publishing, 2010).

[10] Kubota Beisen 久保田米僊, Beisen's Travel Album 米僊漫遊画乘 (發行兼印刷者田中治 兵衛, 1889).

[11] The Traditional Malay House, 23.

[12] Jee Yuan Lim, The Malay House: Rediscovering Malaysia’s Indigenous Shelter System (Pinang, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia: Institut Masyarakat, 1987), 76.