TL;DR

This article examines the increasing attention given to transracial adoptions and adoptees’ journeys to uncover their biological roots. Whilst interest in transracial adoptions has emerged periodically – primarily through media reports and productions that mostly focus on Singapore’s multi-ethnic national identity[1]—this piece contextualises one transracial adoptee’s distinctive personal narrative within Singapore’s historical adoption framework, presenting an account that diverges from typical adoptee experiences.

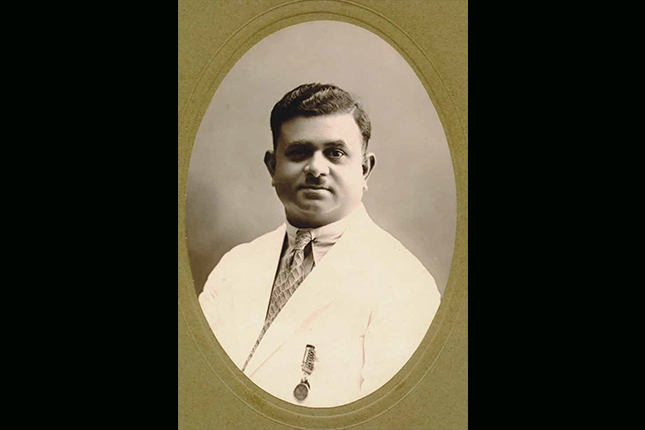

On the evening of 16 August 1940, Neng binte Abdullah, described as a “middle-aged Malay lady”, and her husband, Ibrahim bin Abdullah, found a one-month-old baby boy crying outside their Grange Road home.[2] They took the boy to the nearby police station to report the incident and to make clear their intention to adopt the boy as their own. The very next day, a police inspector declared to a court judge that he was satisfied that Neng and Ibrahim were “proper” and “respectable” persons, fit to take custody of the baby boy. As the baby boy was a Chinese, the case was also likely the first officially recorded instance of a transracial adoption under the Adoption of Children Ordinance enacted in December 1939.

Transracial Adoptions in Singapore, and their Silences

Our investigation into this topic is the result of converging research interests in social services and identity. It takes inspiration from the late Ann Elizabeth Wee’s oral history, where she shared that the “adoption of Chinese baby girls into Indian and Malay families” had intrigued her since the beginning of her distinguished career in social services.[3] Wee found fascinating “the extent to which a Chinese girl could be completely absorbed into an Indian family until it appeared as if everybody [had] forgotten that she wasn’t one of their own ethnic group”. She shared a case of a seventeen-year-old girl, adopted by an Indian family, who found it difficult to believe she was ethnically Chinese when she discovered her adoption status.[4] Wee’s interest resulted in only one short article published in 1977, which was in turn likely inspired by two earlier student research papers on transracial adoption. There is a persistent silence about such adoptions, as one of the student researchers found. She noted a general reluctance among (a) adoptive parents to discuss their children’s adoption status and (b) adoptees themselves, because they did not want to hurt their spouses, children, or families.[5]

The silence is a pity in a way as the adoptees’ experiences—and that of their adoptive parents and families—can help us understand issues salient to identity formation within Singapore’s multicultural society. Most of the documented cases in those research papers involved females, adopted at birth or an extremely young age, and were “entrenched” over time in their adopted ethnicity and culture. Take for instance this case of an eight-year-old boy adopted by a Tamil family after his birth mother’s death. Though aware of his adoption, the boy strongly resisted his Chinese identity, refusing to use his Chinese name and actively identifying as Indian.[6] Hence, any documentation and research into the adoptees’ experiences are precious in shedding light on such moments within the adoptees’ lives. Theresa Devasahayam’s Little Drops: Cherished Children of Singapore's Past is one such recent example. Inspired by her mother’s experience, which collects the biographies of fifteen individuals (mostly women) born to Chinese families and adopted and cared for by non-Chinese families.[7]

Case Study: Madam R’s Adoption Experience

Madam R was adopted by a Malay family when she was about two or three years old. We offer her story as a counterpoint to other cases of transracial adoptions. Unlike other transracial adoptees, Madam R has retained some memory of the transfer between families, knowing from the start that she is Chinese (or different from her adoptive parents).

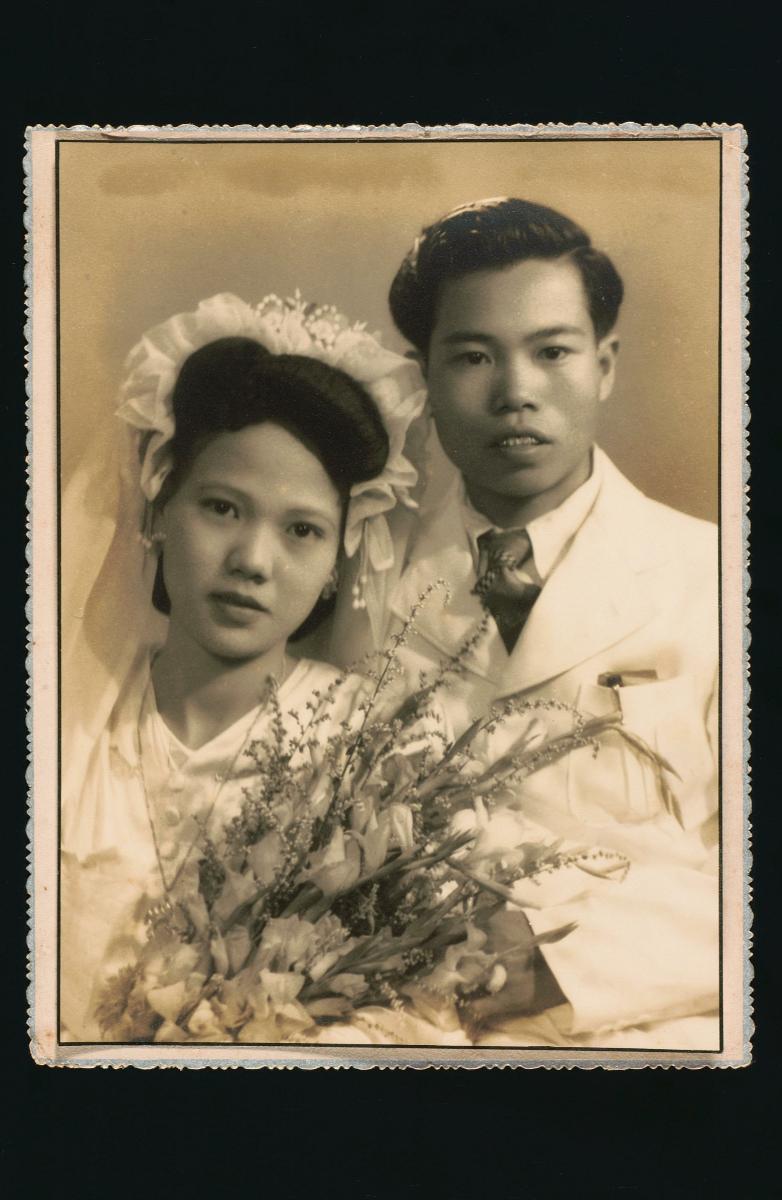

Born on 17 March 1952 in the “Naval Base area” around Admiralty Road and Woodlands Road, her biological father worked as a technician and her mother a coffee aunty in Sembawang Naval Base. Her adoptive parents lived nearby in the police quarters. The adoption arose from her adoptive parents’ inability to have children and their friendship with her birth parents. Both sides were sufficiently close for her then pregnant biological mother to agree to give the unborn child to the adoptive mother. Unfortunately, she miscarried and offered Madam R instead, the second of three girls.

Despite being settled in her adopted family, Madam R’s awareness of her birth family made her wonder about them. While her adoptive parents rarely discussed her adoption, relatives would point out her ethnicity—“Anak Cina”. As a child, she searched through her parents’ drawers, partly in response to Melaka relatives’ comments and her curiosity about her “real mother”.

A significant encounter occurred when Madam R was in Primary 6. Her biological mother visited her adoptive home, introduced simply as a friend. When Madam R declined the luncheon meat her biological mother brought, the latter remarked, “oh lu sudah Melayu ah” (I didn’t realise you’re now a Malay). Though her adoptive mother later questioned what was discussed, Madam R sensed her concern and downplayed the interaction.

Madam R’s story reveals how silence manifested in both her biological and adoptive parents’ actions. (Though over time, she arguably penetrated the “silence” by tracking down and reconnecting with her birth family). While maintaining contact despite possible emotional complications, both sets of parents tacitly agreed to avoid discussing the adoption. This silence was not merely a trauma response, but a viable strategy to maintaining relationships while honouring the adoption agreement. Such stoicism reflected perceived cultural and social norms, balanced by the long-standing friendship between both mothers that enabled the adoption. Silence shaped the life narratives of all those involved and also helped make sense of their liminality.

This research was supported by the National Heritage Board’s Heritage Research Grant.

Notes

- See for instance Channel NewsAsia’s 2002 Mosaic series, Episode 3, Adoptees - The Mahmood family and Episode 7, Adoptee Faizel Neo (Singapore: MediaCorp News, 2002).

- The Straits Times, 18 August 1940, “Woman Applies for Adoption of Baby”: https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/digitised/article/straitstimes19400818-1.2.74.

- National Archives of Singapore (NAS), Oral History Centre (OHC). Interview of Ann Wee (nee Wilcox). 2007.

- NAS OHC, Ann Wee.

- Pereira, “Social Adjustment”, pp.7–11.

- Heng, “The Adopted Child”, Case VIII.

- Theresa W. Devasahayam, Little Drops: Cherished Children of Singapore's Past (Singapore: Penguin Books, 2023). See also media reports on the publication: The Straits Times, 28 January 2024, “Inspired by her mother’s birth story, she wrote a book about inter-racial adoptions in S’pore”.

.ashx)