Text by Nalina Gopal

Images courtesy of Indian Heritage Centre

Be Muse Volume 6 Issue 2 – Jul to Sep 2013

The first official census of 1824 recorded 756 Indians, 7% of the population of Singapore then. In just over a century, by 1931, the Indian population had grown to 50,000 people and continued to grow with time. The dynamic profile of Indian migrants included North as well as South Indians. The early migrants came as British troops or Sepoys, prisoners (political and otherwise) who contributed to Singapore’s infrastructure, traders, plantation workers, professionals and civil servants, policemen, and even as performing artists and craftsmen. These early migrants founded empires and institutions; inspired their community and others; and fought for their rights and beliefs. The increasing number of Indians also gave birth to several associations and organisations that served their agendas of religion, business and trade, arts and culture and even social reform. These organisations continue to be instruments of social bonding and cultural interaction till today.

The Indian Heritage Centre has been delving into this early history of the Singapore Indian community – in the absence of published records, oral history has been pivotal to curatorial research. The Somapah/Basapa family is a perfect example of this initiative.

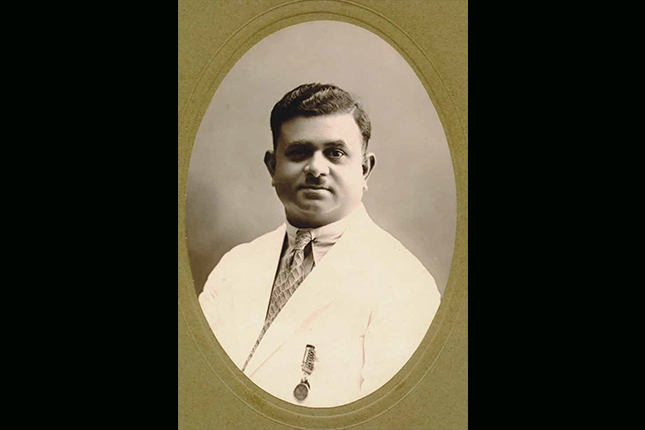

These names were mentioned to me by every other member of the Indian community; he (Somapah) was a pioneer in the property business, they would say. The names kept returning to taunt me, yielding few returns to endless searches at various public archives. Until December 2011, when I found, quite by accident, a family history website created that year by the family of Thomas Augustine (T.A.) Basapa (1917-2010), following his demise. T.A. Basapa was the grandson of Hunmah Somapah (d. 1919) and the son of William Lawrence Soma (W.L.S.) Basapa (1893-1943). With names, context and places made explicit in the content of the website, the public archive search (which included the collections of the National Museum of Singapore, the then Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research and newspapers in Singapore) became more rewarding. I also managed to locate T.A. Basapa’s son Lawrence Basapa, who kindly agreed to be interviewed on the family’s history. Lawrence Basapa has since donated digital copies of photographs from the family album for display at the Indian Heritage Centre.

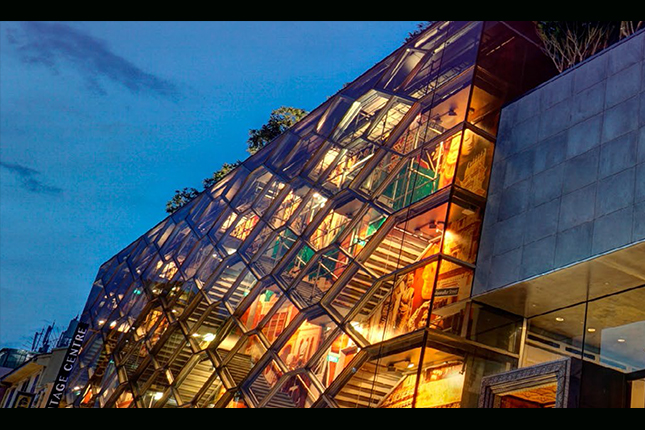

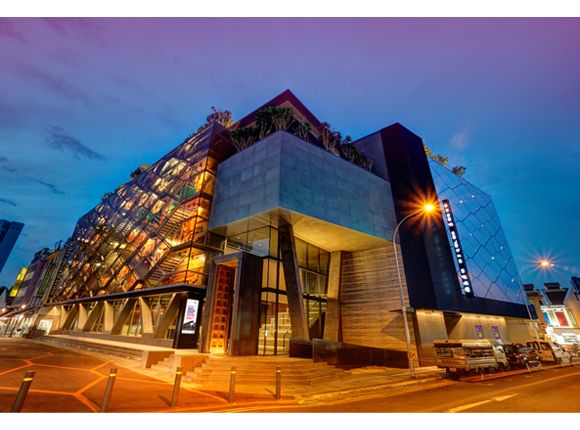

A part of my research findings are compiled below into a short narrative on W.L.S. Basapa (Hunmah Somapah’s son) and his passion for collecting animals, which led to his establishing of Singapore’s first private zoo as well as his contributions to the erstwhile Raffles Museum. Curatorial research on the Somapah/Basapa family forms part of the content for the Indian Heritage Centre’s permanent gallery on Indian Pioneers in Singapore. Please visit us at the junction of Campbell Lane and Clive Street to know more about this remarkable individual and other Indian pioneers in Singapore. The Heritage Institutions Division under the National Heritage Board has also produced a travelling exhibition on Singapore’s Early Zoo which features photographs and the history of the first Singapore zoo at Punggol. The exhibition was launched at the Singapore Zoo in April 2013 and travelled to three National and Public Libraries in Singapore.

W.L.S. Basapa: Pioneer and Collector

Hunmah Somapah was a landowner and municipal official. The Somapah estate owned properties in the Serangoon Road and Changi areas. Upon Somapah’s death, W.L.S. Basapa became a trustee of the Somapah estate and inherited his father’s residence at 317 Serangoon Road. It was at his Serangoon estate that he began, between the period 1920 and 1922, to collect several species of animals and birds.

To accommodate his growing collection of animals and birds, Basapa acquired 11 hectares of seafront land at Punggol. In 1928, he relocated his collection to Punggol and started the Singapore Zoological Gardens and Bird Park at Punggol (also known as the Punggol Zoo).

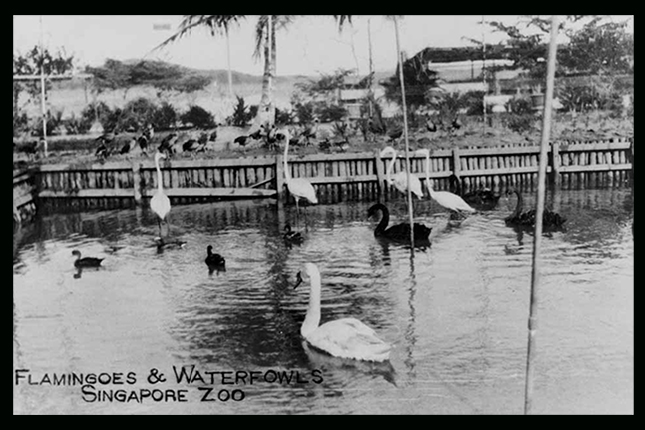

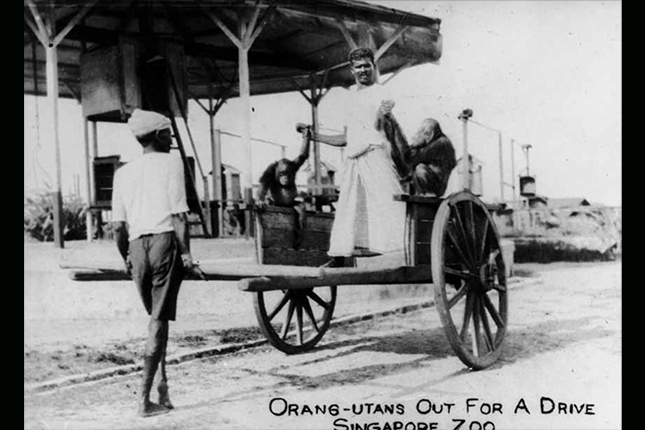

It took ten years for Basapa to transform the muddy and overgrown piece of land in Punggol into a full- fledged zoo. At the rate of S$35 per day, Basapa maintained the zoo privately from 1928 until the start of World War II. Basapa was a man of foresight who forged international connections to create the best displays at the zoo. For instance, Basapa imported a stunning black leopard (announced as a Black Panther in a 1937 Straits Times article) for the Punggol Zoo from Sydney’s Taronga Park Zoo in 1937. This was part of an animal exchange plan devised between the two zoos. He also brought in exotic animals from South Africa, America and Australia, and eventually built up a collection of 200 animals and 2,000 birds for the Punggol Zoo.

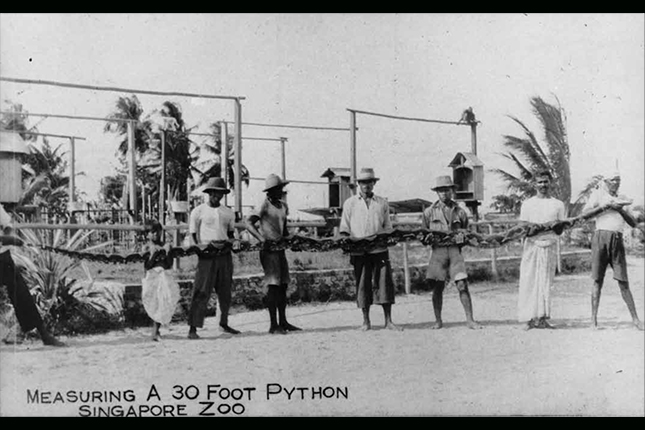

The zoo was a major attraction in pre-war Singapore and charged a nominal entrance fee of 40 cents. It even gave discounts of up to 75% off the entrance fee for students. In fact, the Punggol Zoo was known the world over, and even locally, as the Singapore Zoo – the first to be called so.

At the start of World War II, the British moved their forces to the North of Singapore in anticipation of the Japanese onslaught and occupied the site of the Punggol Zoo. Basapa was given 24 hours to vacate his animals and birds, and given the short time span, was unable to save all of his animals. The British freed the birds and harmless animals and shot the more dangerous ones.

During the Japanese occupation, the Punggol Zoo became the location for the Japanese mess, and Basapa eventually died in 1943, a broken-hearted man. The Punggol Zoo was not restarted by the Basapa family after the war.

In his lifetime, Basapa made periodic, almost annual, donations to the Raffles Museum between the years 1924 and 1938. These donations included animal skins and mounted specimens of animals that had died at Basapa’s home zoo at Serangoon Road and later at the Punggol Zoo. The Raffles Museum’s annual reports (in the collection of the National Museum of Singapore) mention Basapa’s generous donations to the Museum’s collection of zoological specimens. More than 80 specimens donated by Basapa were later inherited by the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research (now Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, National University of Singapore) from the former Raffles Museum and are still part of the museum’s collection.

Nalina Gopal is Assistant Curator, Indian Heritage Centre

Milestones of the Punggol Zoo

According to contemporary newspaper articles, the famous physicist Albert Einstein visited Singapore in November 1922 to raise funds for a proposed Hebrew University in Jerusalem. His notes on this visit mentioned his passing through “Singapore’s Zoological Gardens”. This is possibly a reference to Basapa’s private home zoo located at 317 Serangoon Road.

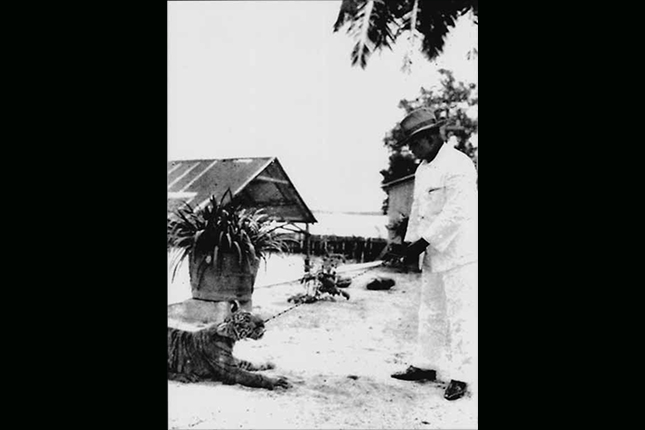

Basapa’s Punggol Zoo was commended by Sir Roland Braddell in his 1934 book Lights of Singapore. Braddell also mentioned Basapa’s “magnificent collection of birds”, his orang-utans and a pet tiger named Apay that could be led around by a chain even though he was four years old.

In March 1930, the Punggol Zoo imported seals into the British colony of Singapore. This marked the first time members of the public could view these marine creatures in a public zoo.

A 1933 American film titled “Dyak” starring English actor M.H. Kenyon-Slade was shot at the Punggol Zoo. Kenyon-Slade was filmed fighting a dead python in a battle which was regarded as one of the high points of the film.

In February 1935, the newspapers reported that the Punggol Zoo had received several Arabian camels, black swans and Shetland ponies from the Perth Zoo. The following year, the Punggol Zoo produced advertisements to promote a café that served afternoon tea at the Zoo. The café was in fact an open-air “refreshment room” that served tea, biscuits and lemonade at a low price.