By Christine Van Assche & Patricia Levasseur de la Motte

BeMuse Volume 4 Issue 3 – Jul to Sep 2011

The 2011 exhibition Video, an Art, a History 1965–2010 presented at the Singapore Art Museum (SAM) a selection of video works from the Centre Pompidou collection, in resonance with works from the SAM collection. About 50 works were shown at SAM and SAM@8Q. It was a pilot exhibition bringing together two institutional collections: one that began in France in 1976 with works from 1965 till today, the other since 2008 in Singapore; one turned towards major international trends, the other steered towards Asian works – more specifically those from the currently very prolific region of Southeast Asia.

Nowadays, most international exhibitions, biennales, museums of contemporary art, certain private collections and even contemporary art fairs exhibit and present video works in diverse forms. The exhibition recounted the development of video art from 1965 to 2010 in six main themes.

Utopia and Critique of Television

Video was born in the 1960s into two contexts: those of the fine arts – performance art in particular – and television production and broadcasting. The first section of the exhibition presented works which explored the processes of television production, the political and social influence of the media as well as the role of the viewer. Television here appears as the key subject of the works and the medium of production and broadcasting. Video is thus shared between television and artistic creation.

At first, some artists explored the television set as an object by placing it within the artistic and displaying it in exhibitions. The first to do so was Korean artist Nam June Paik who made use of the signal emitted by television sets. He manipulated it in a very minimalist way in the installation Moon is the Oldest TV, realised in 1965, and later in the video Global Groove, produced for the New York television channel WNET in 1973.

Other artists like Valie Export in Austria in 1971 and Bill Viola in the United States in 1983–84, question the role of television audiences and adopt an ethnological approach to this ‘new population of spectators’. The screen becomes a mirror reflecting the attitude of this new ‘ethnic group’. Some other artists examine television programmes from a more critical angle, studying their strengths, powers of attraction and flaws. In the works of Sonia Andrade and Mako Idemitsu, video deflects television broadcasts to serve critical purposes, analysing semiologically their content in the 1970s and 1980s.

Issues of Identity

In the 1970s, video art entered a period of social and political revival marked by student movements, the rise of feminism and demonstrations against war and racism. Following Joseph Beuys’ idea that “every man is an artist”, the human body becomes a piece of artistic and aesthetic material. In this context, video registers, deconstructs and recreates performances by artists, whether in public or alone in their studio. In the latter case, the camera becomes the only witness to artistic expression. The human body – the artists’ and actionists’ primary instrument – most often expresses feelings of pain, violence (Vito Acconci) and desire, but also objectified physical experience which transforms the body into analogical codes, such as in the work of Toshio Matsumoto.

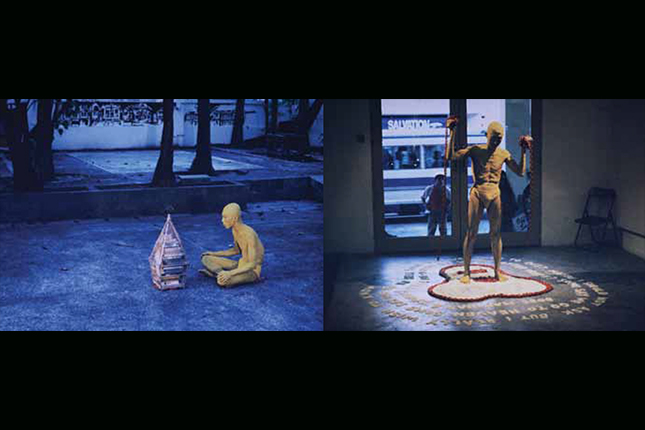

In 1988, Jean Baudrillard posed this question: “Am I a man or a machine?” Valie Export belongs to the first generation of women artists who challenged a patriarchal media society, using the female body to combat fossilised stereotypes. As for Sonia Khurana, by showing her denuded body, she attacks clichés about conventional ideals of beauty. The integration of the public into performances or as a participant in video installations leads to an interactive reflection on the role of the individual in our society, as in the works of Lee Wen and Joan Logue. In 1996, Tony Oursler conceived the installation SWITCH, a circuit of mise en abyme within the museum itself, which incorporates the visitor in an imaginary narrative throughout his or her visit using ‘talking heads’ and surveillance cameras, while at the same time questioning our contemporary world populated with cameras and surveillance systems.

From Video Tape to Interactive Installation

The 1960s and 1970s were conducive to research in phenomenology, parapsychology, conceptualisation and technology. In art, the emergence of video coincided with the acceptance of performance art and the arrival of installations.

This section examines representations of the self and the other, especially through the placement of the body in space. Artists such as Bruce Nauman began to document their performances on videotape before delegating the role of the performer to the viewer who is also bound by the conditions of museum space. In the age of minimalism and conceptual art, artists like Martial Raysse, Peter Campus, Dan Graham and Bruce Nauman transformed the visitor into an active and indispensable parameter of the artwork which cannot otherwise function. This is seen in Raysse’s picture, Graham’s mirror and Nauman’s white cube (in connection with the works of author and playwright Samuel Beckett).

Most of the works in this section employed the closed circuit (a video camera linked to a monitor) or the surveillance circuit. The screen is likened to a window or a mirror, and the camera to the eye. The visitor is often filmed unbeknown and his or her image is reversed, delayed or displaced several metres away in a meticulously designed space.

Landscape Dreams

The Chinese concept of landscape (shanshui) has two basic elements, mountain (shan) and water (shui), and has inspired countless poets and painters. Using ink and brush, China’s greatest artists strived to transcribe their contemplations on paper or silk. In this artistic practice, which is one of the noblest, the quest for the Way (Dao) and breath resonance (qiyun) unites the artist and nature through meditation (Toshio Matsumoto).

The mountain is also the land of myths and legends, feared at times, venerated at others and sometimes even deified. In Asia, Mount Wutai in China and Mount Fuji in Japan attest to this (Ko Nakajima). After sojourning in Japan, artists living in the United States (Bill Viola) and in France (Thierry Kuntzel) have expressed an interest in landscape as a metaphor for time and space. Both of these artists, who filmed in Japan, present man with the infinity of the landscape in their exhibited works.

The urban landscape has become a recurrent theme in contemporary video art. With the largest number of megalopolises in the world today, Asia’s transformation over the last few years has been rapid and dramatic. Urban dynamics (Louidgi Beltrame), population influxes (Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba), architectural renewal (Rachel Reupke) as well as the effects of globalisation (The Propeller Group) and the loss of natural spaces or local patrimony (Keith Deverell, Sue McCauley, Meas Sokhorn, Srey Bandol) preoccupy the artists in their video works. The natural landscape – the field of meditation and contemplation – confronts the urban landscape, the theatre of a passive and apprehensive observation.

Memory: Between Myth and Reality

In the post-Marxist era, especially in countries with emerging contemporary cultures, artists prefer to use digital media like photography and video to express themselves. The evolution of a new geopolitical map of creation has picked up pace over the past few years, affecting most parts of the world, including the Balkans, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. It should be remembered that from the 1960s to 1980s, video artists came largely from North and South America, Japan, and Europe.

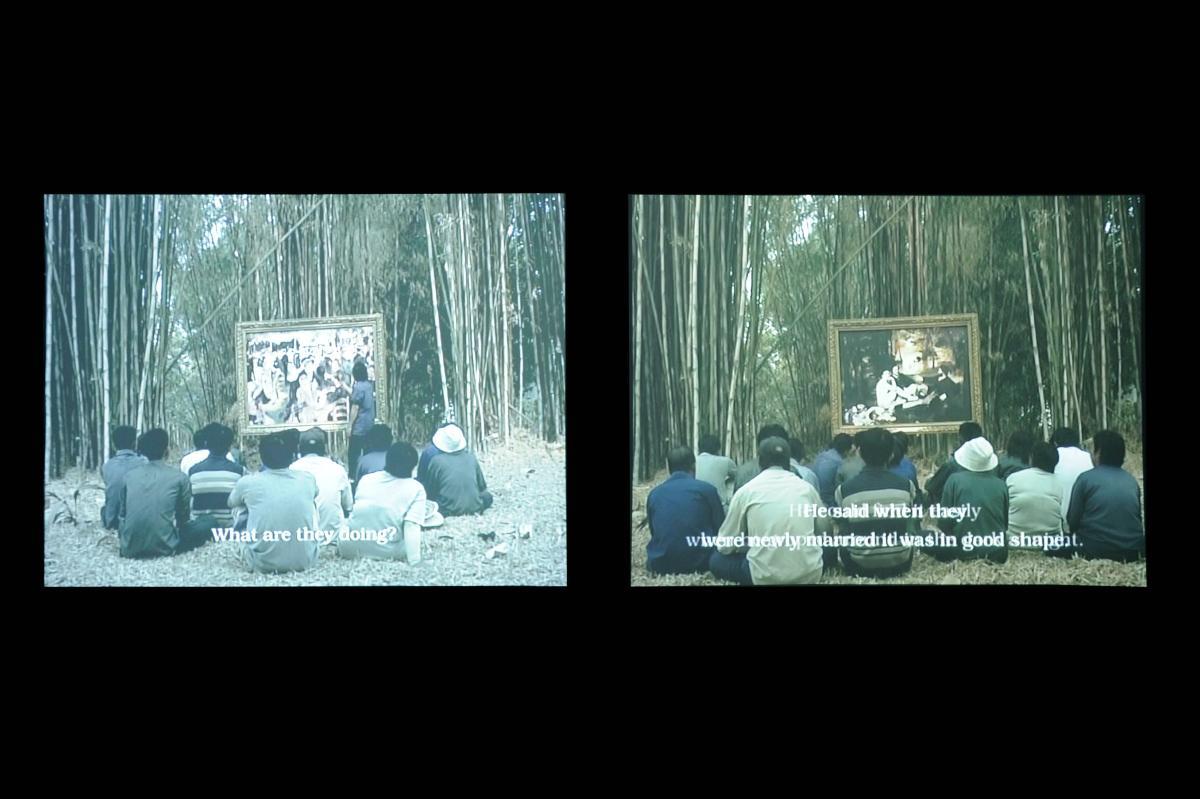

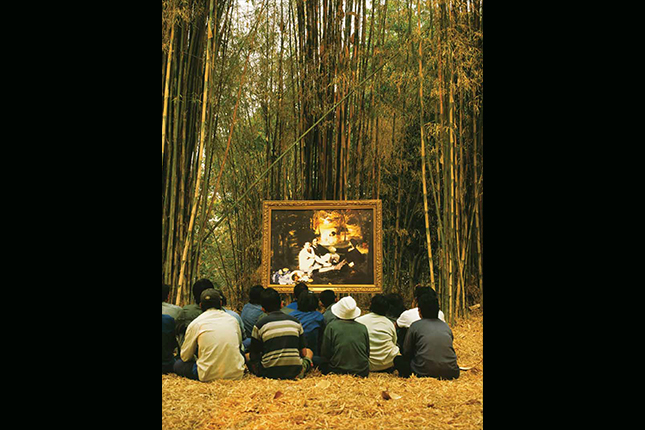

The artists in this section focused on questions linked to the reality of their world, of our world – political reality (Liu Wei), ethnological reality (Sima Salehi Rahni), cultural reality (Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook), religious reality (Than Sok), and sociological reality (Arahmaiani) – and transformed them into artistic works that are generally poetic. Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y is the symptomatic title of Johan Grimonprez’s work that revisits historical events in a poetic, and certainly subjective, way.

By adopting the documentary style, artists stay close to historical reality. They sometimes replay, interpret, and comment upon isolated fragments of reality (Richard Streitmatter-Tran) through technical interventions like cuts, shots, sound, language, and special effects (Dinh Q. Lê). The format of documentary rests upon the tradition founded on experimental cinema and the works of filmmakers like Chris Marker. Today, a new generation of artists offer a distinct perspective on their community that has become global, most notably through new media such as the Internet. Video thus acts like a memory exercise of societies, transposing events often situated on the boundary between myth/fiction on one hand and reality/history on the other.

Deconstruction and Reconstruction of Narratives

The sixth section of the exhibition explored the crisis of narratives and the end of representations with works from the 1980s to 2009: six artists deconstruct images and sounds from their cinematographic culture (Jean-Luc Godard, Pierre Huyghe, Yang Fudong, Isaac Julien, Tun Win Aung and Wah Nu). Video art has much evolved since Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle towards spectacular installations involving video projections, large screens and multidirectional sound in specially devised dark spaces that resemble auditoriums for some (Julien) and staged exhibitions for others (Huyghe).

Video artists now look to the professionals of documentary, narrative film and television series for resources. Shooting with professional teams, and editing and sound mixing in studios are common practices in art. Sound itself has become an incontrovertible element of video installation and is handled with great care. Some artists shoot their own images and record their own sound (Julien, Yang), while others appropriate images and sounds from existing films, borrowing and mixing filmed images and recorded sounds (Huyghe). The purpose of these manipulations of images and sounds is to recreate newly structured narratives that are closer to contemporary concerns. Installation here gives way to various modalities. By including the visitor in the work’s space, the visitor actively becomes one of the work’s constituent and necessary parameters.

Conclusion

Today we cannot but notice the proliferation of works using digital tools such as video, photo and sound. Video has been in existence since 1960, for half a century at the time of writing in 2011. Nonetheless, during these 50 years, video has made considerable progress, not only in pushing against the frontiers of aesthetics but also in the fields of technology and art history.

Christine Van Assche is Chief Curator, New Media Department, Centre Pompidou. Patricia Levasseur de la Motte was formerly Assistant Curator, Singapore Art Museum.