Batik is a traditional art form that uses coloured dyes and wax to create patterns on a material, typically a cloth, and the patterned cloth itself. A batik artist would design patterns on cloths using a wax resist technique through copper stamps or by hand, and then dye the cloths to produce colourful designs. After the dyeing process is complete, the cloth will be soaked in a dye solution, which is often derived from natural materials.

Batik designs are intricate and complex, requiring high skills, creativity and expertise in the art. Often, a piece of batik takes a few days, and sometimes months, to be completed. The labour-intensive art form reflects the commitment and dedication of batik artisans to their craft.

Though the art form is practised in many countries across the world, the royal courts of Yogyakarta and Surakarta of Central Java are well-documented as important, original centres of batik production and development, handmade by aristocratic women exclusively for the nobility.

Batik became mainstream with the growth of batik workshops outside of the royal courts, and batik producers were able to experiment and create diverse motifs to cater to local and foreign tastes. New motifs were created, influenced by various cultures, including from the Eurasian, Chinese and Arab communities.

Common Batik Motifs

In making batik, the wax resist technique is repeated to form repetitive and intricate patterns, or motifs. Generally, these motifs represent specific philosophies and values of the batik wearer or their region of origin. Some even have symbolic importance and are meant to be worn only on specific occasions. Each region in Indonesia, for instance, has its own distinctive batik motifs that represent its beliefs and culture.

One popular motif is the parang motif which dates to the Mataram Kingdom in the 16th century, making it the oldest batik motif in Indonesia. The Yogyakarta-originated motif features wave-like, s-shaped patterns arranged diagonally and represents the sea waves south of the city. As the name “batik parang” suggests — “parang” means “sword” in Javanese — the motif symbolises strength, status, and power. As such, during the Mataram sultanate, the motif was reserved for nobility and royalty. This exclusive practice shows the hierarchical nature of Javanese society, the importance of clothing as status symbols, and the significance of batik to the royalty and society at large.

Another popular motif is mega mendung (literally “cloudy skies” in Javanese), which hails from the royal court of Cirebon in West Java. The motif features cloud-like designs symbolising tranquility and serenity.

The Best of Both Worlds: Tumadi Patri’s Journey with Batik and Wayang kulit

Batik motifs and their meaning evolve over time thanks to practitioners of the traditional art form. Some may create new motifs or reinterpret them.

Others have found new and unique ways to engage with batik, such as Singaporean-born and raised practitioner Tumadi Patri. Tumadi graduated from the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) in 1986 and from Pa Lin School of Art in 1991. Tumadi began experimenting with batik as early as 1983, pairing it with wayang kulit — a traditional form of shadow puppetry with roots in various Southeast Asian cultures, including Javanese, Balinese, and Indian traditions — as an ode to his Javanese background and to his grandfather, who was a practitioner of the art form.

To develop his skills, he began tutelage under the wings of senior artists at APAD (Angkatan Pelukis Aneka Daya or Association of Artists of Various Resources), one of the oldest art societies in Singapore, in 1983. He attended the association’s classes where he learned under the tutelage of senior local artists like Mohamed Abdul Kadir (Mohdir), Sarkasi Said, and Sujak Rahman.

He also travelled to Malaysia, Solo, and Yogyakarta, Indonesia, to deepen his knowledge in batik motifs and wayang kulit characters, as well as their philosophies. “Understanding the philosophy, identity (of the motifs and characters), and wayang kulit stories was crucial to help me understand how I can combine both batik and wayang kulit to create a coherent work that accurately described the themes I wanted to depict,” he said in an interview.

He noted that this was not a conventional approach at the time. “I just gave it a try. Whenever I braved myself, even if there was resistance from others, I just did it,” he added. “There are no prohibitions or boundaries (in art) so I tried.”

Among his experimentation was using a different medium for wayang kulit puppets, which are typically carved on animal hide like the buffalo. Instead, he pasted the puppets on a canvas and designed them in traditional wayang kulit outfits or dyed them with natural and bright batik dyes.

His passion for the art form ran so deep that he jokingly recounted taking “medical leave” from work to make time to complete his batik orders. “Most of the orders were from Malay teachers who wanted to use original batik pieces as class materials in art and culture lessons. They typically asked for images of kampung, nature, and animals such as butterflies,” he said.

For his commitment and dedication, Tumadi has been awarded many accolades. In 1990, he received the High Commendation prize at the IBM Art Awards and the Singapore Telecom Expression Art Competition in 1997. He was also awarded the Certificate of Distinction in the Philippe Charriol Art Foundation Contemporary Art Competition, Singapore in 1995.

He had his first solo exhibition in 2014 at the DLR Gallery@Muse House, but prior to that, his works had already been featured in various local and international exhibitions in the Netherlands, Australia, Malaysia, and Indonesia since the 1980s. A notable recent exhibition was the 13th Biennale Florence in 2021.

Reimagining Batik

Tumadi Patri’s combination of batik and wayang kulit deviates from tradition in more ways than one. Besides combining two traditional art forms, he uses bright colours in his work when both art forms typically use natural and earthy tones, according to him. There are several reasons for this choice: to establish his signature style as an artist, and to bring the art forms to an international level, which generally finds bright colours more appealing.

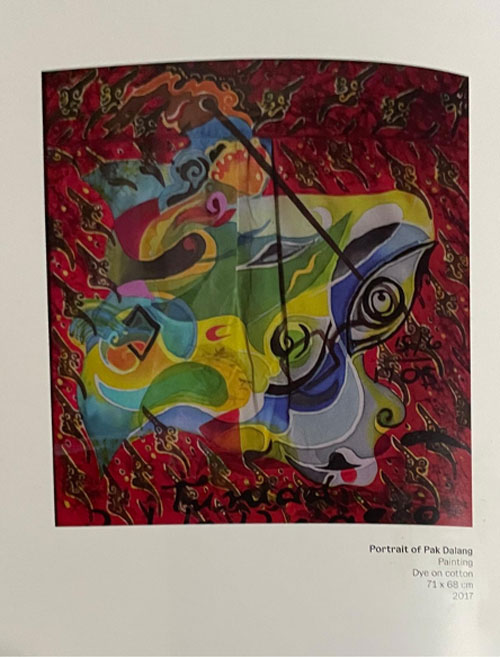

Colours also play functional and artistic roles. There is a strong link between colours and the images, with the strong and vibrant colours reinforcing the message behind his works, making them “complete”. “Unlike a wayang kulit performance, paintings don’t have a ‘Pak Dalang’ (puppet master) narrating the story. So the colours in my batik and wayang kulit paintings are especially important to encapsulate my work’s meaning. In a way, the colours themselves tell the story of the painting, like a Pak Dalang of a performance,” he explained.

As a Singaporean-based artist, Tumadi’s wayang kulit art also has to contend with certain limitations. For example, the wayang kulit puppets are traditionally carved on animal hide. The choice of material is a defining feature of wayang kulit, Tumadi argued. “With buffalo or cow skin, the puppet can last very long. That is what makes it valuable, that it can last for hundreds of years, especially if it is well-maintained.” However, since it is impractical to be faithful to the original material in Singapore, he uses other materials, such as reinforced thick cardboard on which he sketches the puppets, paints, and varnishes them.

Looking ahead, Tumadi is optimistic about the prospects of batik in the hands of the next generation, with some young practitioners standing out to him. While he has hopes that the art of batik will flourish, he emphasised the importance of developing the art form in a deep and substantial manner based on a deep understanding of the philosophy and symbolism of batik, which he considers to be the ‘heart’ of the art form.

About the Writer

Nur Hikmah Md Ali is a writer and poet. She has published poems, commentaries and essays on several platforms, including Berita Mediacorp and the Malay Heritage Foundation. In 2021, she was nominated as a Sahabat Sastera (Friend of Malay Literature) by the Malay Language Council, Singapore. She joined the Singapore Book Council’s 2024 mentorship programme as a mentee under the Malay poetry category. She is also a member of Meja Conteng, a youth collective comprising young Malay writers who are passionate about Malay literature and arts.

Notes

- Roslinda Rahmat. (2023, September). Genderang... Pusaka Yang perlu dilestarikan. Gaya Hidup. https://berita.mediacorp.sg/gaya-hidup/genderang-pusaka-yang-perlu-dilestarikan-785216

- National Heritage Board. (2020, November). Making and repairing of Malay drums. ROOTS. https://www.roots.gov.sg/ich-landing/ich/making-and-repairing-of-malay-drums

- Lim, C. K. N., & Mohd Fadzil Abdul Rahman. (2011). Preventing Malaysia’s traditional music from disappearing. SPAFA Journal, 21(2), 37-47.

- Yampolsky, P. (2001). Can the Traditional Arts Survive, and Should They? Indonesia, 71, 175–185. https://doi.org/10.2307/3351460

- Chaika, O. (2024). Bridging the Gap: Traditional vs. Modern Education (A Value-Based Approach for Multiculturalism). IntechOpen. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.114068