In various Malay cultural occasions or ceremonies, the songkok remains as a significant element in the male traditional attire. Some hold the view that this Malay cultural heritage can be traced as far back as the Ottoman era. This traditional headgear is typically crafted from black velvet or felt material or even coloured in different designs. While many men today are able to purchase ready-to-wear songkok off the shelves, the meticulousness nature of crafting one by hand should not go unnoticed.

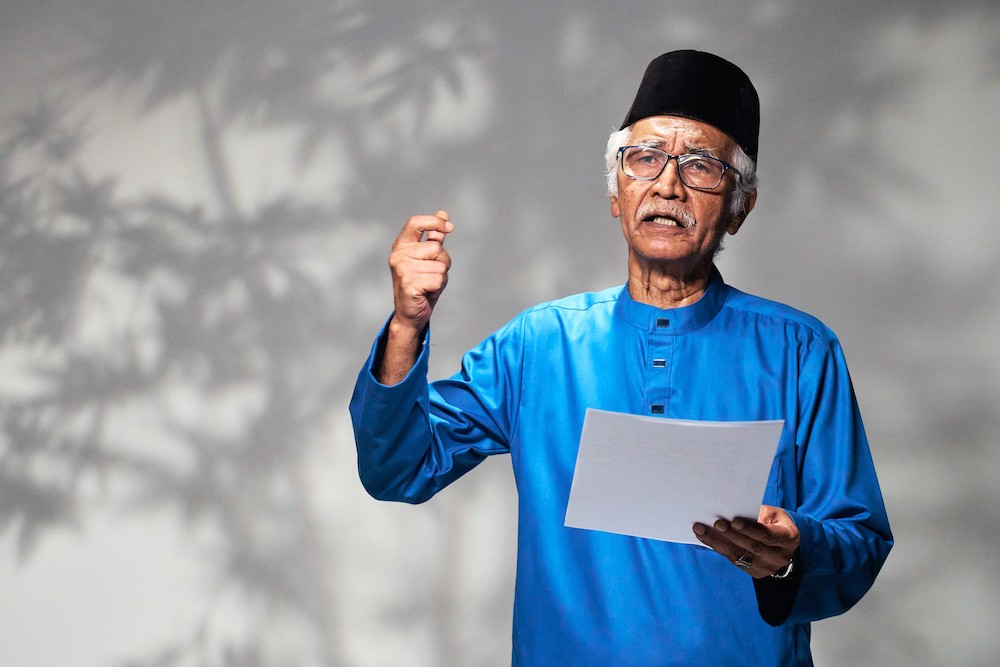

Abdul Wahab Abdullah, 65-year-old, is one of the few remaining songkok makers left in Singapore who still continues to produce custom-made songkok for his customers. Abdul Wahab’s lifelong experience in songkok making holds deep memory and history with his father, Abdullah Samad. His father, who migrated to Singapore from Indonesia, was also a songkok maker and had instilled the love for the art of making songkok.

The Start of the Songkok Journey

Abdullah Samad was a trishaw puller from 1948 to 1970. In 1967, he took a leap of faith to open a shop at the old Geylang Serai Market. However, to cover the increased rental rates of the shop, Abdullah Samad had to sell off his trishaw. Hence, Abdullah Samad chose an image of a trishaw as the logo for his handmade songkoks to symbolise the dedication and effort that he had invested into starting a shop. To honour his father, Abdul Wahab retains the use of the trishaw in the brand his father founded, and renamed it ‘Songkok Beca’ (Trishaw Songkok).

It was at his father’s shop that the young Abdul Wahab, at the age of 7, started learning the trade. His motivation in learning the art of making songkok stemmed from witnessing his father’s dedication in this craft. It struck him as to who would continue his father’s legacy when he is not around anymore. It was in that moment Abdul Wahab decided that one day he would succeed his father and continue to preserve the art of this craft. He then learnt the process of crafting a songkok which includes delicate precise steps such as measuring and stitching fastidiously. He eventually managed to create his very own songkok after four years of training, at the age of 11.

Songkok as the Ornament of the Head

The precision of making a songkok requires a combination of craftsmanship, technique, and attention to detail. Each step in the process, from selecting the materials to the final stitching, demands accuracy to ensure a well-structured and aesthetically refined product. For Abdul Wahab, the most challenging process of making the songkok is ensuring the stitches are neat when combining the top part of the songkok with the base of it, also known as the ‘body’ of the songkok.

The design details of a custom-made songkok are carefully tailored to complement the wearer’s facial features. For individuals with smaller head and body proportions, the songkok should not exceed 4 inches in height. In contrast, those with rounder facial features are best suited to songkoks measuring 4.5 inches or taller, ensuring a well-balanced appearance.

The Purveyor of Culture Songkok for the Community

Reflecting on his own experiences, Abdul Wahab said that as a child, he noticed the songkok was a key part of traditional attire, especially during Hari Raya. It almost felt mandatory to wear one during celebrations. It would be deemed as ‘incomplete’ to dress up in the traditional baju Melayu without the songkok. To many, the wearing of songkok as part of the whole attire is a representation of Malay cultural identity.

In his shop, Abdul Wahab used to produce around 2,000 songkok annually. The busiest period would be during Ramadan, when families order multiple songkok for Hari Raya Aidilfitri. Many of his customers have been returning for generations, dating back to his father’s time. As the only full-time songkok maker in Singapore, Abdul Wahab plays a vital role in preserving the craft, ensuring the community is well-adorned with this traditional headgear when wearing cultural attire.

However, in this day and age, with the ever-evolving globalisation and modern cultural fashion, the songkok has seen a decline in use. Abdul Wahab has noticed that it’s not unusual to see Malay men wear the traditional baju Melayu without their headgear. While Abdul Wahab acknowledges the shift in preferences and trends, it does not dampen his spirit to continue producing songkok. Abdul Wahab understands that no matter how modern a society is, the songkok still holds a valuable position in the Malay community and that people will still wear it during important occasions and ceremonies.

That being said, Abdul Wahab understands the needs and demands of modern society when it comes to marketing his songkok. Two years ago, after multiple relocations from Geylang Serai Market to Tanjong Katong Complex and then City Plaza, Abdul Wahab shifted to a warehouse at Bedok to continue his songkok trade. To reach a wider audience, he has also taken his business online with the help of his son. By promoting his business online via the ‘songkokbecaworldwide’ Instagram page, it has stretched his business internationally.

Abdul Wahab has received orders from around the globe, including countries like Japan, Australia, Nigeria, and the United Kingdom. While he is unsure of the identities of these international customers, he is also appreciative that these buyers are willing to pay high shipping costs, even higher than the price of the songkok itself. However, the majority of his orders still come from local customers in Singapore. His customers in Singapore comprise long-time patrons and new ones who discovered his shop and services through social media.

Preserving The Heritage of The Dying Trade

It is not an exaggeration to recognise Abdul Wahab as the custodian of Singapore's songkok heritage, given that he is the sole craftsman in this field of songkok production. While many people wear the songkok, the number of skilled makers or craftsmen is disproportionately low. Abdul Wahab observes that, over the years, as veteran songkok makers have passed on, they have left no successors to carry on the craft for the community. Concerned about this situation, Abdul Wahab hopes that his children will learn the craft from him and eventually carry on his legacy. Although he remains hopeful, Abdul Wahab believes it is unnecessary to impose expectations or pressures on his children or the younger generation to inherit the responsibility of songkok making.

Be that as it may, Abdul Wahab receives constant support from his wife and three children. Regarding the future of his business, his children have been involved from a young age, assisting with minor stitching and managing the online aspects of the enterprise. Among them, his youngest son has shown the greatest interest in taking over the business, despite pursuing a career in the police force.

Given his good health, Abdul Wahab does not intend to fully retire from making songkok. Abdul Wahab feels that he still carries the responsibility of serving the community by producing quality songkoks for them.

Notes

- Roslinda Rahmat. (2023, September). Genderang... Pusaka Yang perlu dilestarikan. Gaya Hidup. https://berita.mediacorp.sg/gaya-hidup/genderang-pusaka-yang-perlu-dilestarikan-785216

- National Heritage Board. (2020, November). Making and repairing of Malay drums. ROOTS. https://www.roots.gov.sg/ich-landing/ich/making-and-repairing-of-malay-drums

- Lim, C. K. N., & Mohd Fadzil Abdul Rahman. (2011). Preventing Malaysia’s traditional music from disappearing. SPAFA Journal, 21(2), 37-47.

- Yampolsky, P. (2001). Can the Traditional Arts Survive, and Should They? Indonesia, 71, 175–185. https://doi.org/10.2307/3351460

- Chaika, O. (2024). Bridging the Gap: Traditional vs. Modern Education (A Value-Based Approach for Multiculturalism). IntechOpen. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.114068