Nyonya Beadwork and Embroidery

Nyonya beadwork and embroidery are intricate craft forms associated with the Peranakan community, and can be found in decorations for everyday household items, as well as more ornamental pieces for special occasions such as weddings.

Nyonya beadwork uses coloured glass and metal seed beads that are 1mm to 2mm in diameter. The most commonly used beads are the rocaille (round beads with no flat sides) and charlotte (facet-cut) glass seed beads. They are often used together. They may be stitched individually (seed or petit-point stitching), strung on a thread that is fastened on the fabric with a second thread (bead couching), or sewn to the fabric one or two at a time (lane stitching).

Nyonya embroidery borrows closely from the Chinese embroidery tradition in its use of materials, motifs, and stitching techniques. Threads of all colours are used, as well as metal purls and bullion, which are “very fine spring-like threads that are hollow through the centre”.

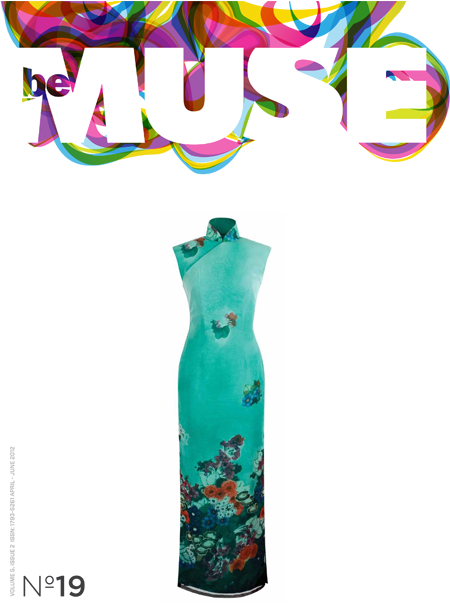

While several items could be embroidered or beaded, two iconic examples are the beaded slipper (kasut manek) and the traditional dress of sarong kebaya.

In the 1930s, beaded and embroidered slippers were worn by both Peranakan males (Babas) and females (Nyonyas), but now they are mostly worn by females. The kebaya, said to be derived from the Malay baju panjang, uses voile (a soft, sheer fabric) as a base material and features two triangular front panels (lapik) that fall over the hips. Various stitches are used to create designs on the fabric. Similar to Nyonya beadwork, embroidery patterns show European influences in their use of floral and animal motifs.

Geographic Location

Besides Singapore, Nyonya beadwork and embroidery is also practised in Penang and Melaka in Malaysia. Many embroidery items in Peranakan homes have been linked to embroiderers in Canton, Fujian, and Zhejiang in China.

Communities Involved

The Chinese Peranakan community is the main community involved, and the community in Singapore can be traced to the Chinese who settled in Melaka during the 14th century and married local women of Malay, Javanese, or Balinese heritage.

The community set up the Straits Chinese British Association in 1900 which eventually evolved into the Peranakan Association of Singapore in 1966. Associations such as the Gunong Sayang Association in Singapore also promote the culture of the Peranakan communities.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

Nyonya beadwork and embroidery were usually made by female Peranakans. Skills and knowledge were passed down from grandmothers and mothers. These crafts were used to decorate wedding-related items. The bride would bead and embroider the groom’s slippers and belt. Motifs associated with weddings include pairs of ducks to symbolise conjugal fidelity and phoenixes representing the couple.

Although mostly linked with women’s clothing, embroidery was also used on parts of men’s clothing. Peranakan men used to wear loose, unstructured clothing that was secured by tying a sash around the waist. The sash would be embroidered at both ends. Babas also wore beaded shoes up to the middle of the 20th century.

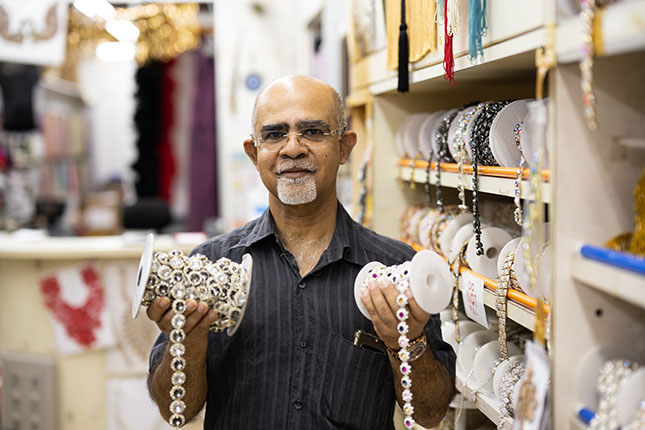

Experience of a Practitioner

Mr Raymond Wong Sin Kong is a practitioner of Nyonya beadwork and embroidery in Singapore, and a fashion designer at Rumah Kim Choo boutique in the Joo Chiat area of Singapore. A third-generation Peranakan, he grew interested in beadwork and embroidery in 2005. His first beading project was a pair of men’s shoes which took 18 months and more than 54,000 beads to complete. After that, he bought computer software to sketch and print his designs. This helped him to complete his subsequent projects faster.

Mr Wong notes that the beadwork in Singapore shows Indian influences in its use of gold thread. Also, while artefacts in Penang and Melaka mostly used traditional Chinese designs, those in Singapore leaned towards Victorian-inspired motifs, such as dogs.

Watch: Nyonya Beadwork

Mr Wong also makes and embroiders kebayas from scratch and by hand, aided by a sewing machine. He is one of two such kebaya makers in Singapore, the other being Mr Heath Yeo. Today, beading classes are held by some Peranakan boutiques such as Rumah Kim Choo, and Mr Wong teaches embroidery classes at LASALLE College of the Arts. To Mr Wong, Nyonya beadwork and embroidery is an important part of Peranakan culture and should be kept alive. “It can be sustained as long as (there are) people who are interested in it,” he says.

Present Status

Significant financial costs are involved in Nyonya beadwork and embroidery. Special sewing machines are required to produce the tension needed for embroidery, and beads are usually purchased in quantities of 25 kg to 50 kg per colour. Also, the beaded or embroidered items are expensive and take time to sell.

A resurgence in interest was in part due to the popular TV series Little Nyonya, which debuted in 2008 in Singapore. It was later aired in places including Malaysia, Cambodia, Thailand, Philippines, Hong Kong, and China, as well as the United States. The Peranakan Museum also ran an exhibition on Nyonya beadwork and embroidery from 2016 to 2017. These efforts contribute to raising awareness on the culture and the crafts continue to appeal.

References

Reference No.: ICH-044

Date of Inclusion: April 2018; Updated March 2019

References

Cheah Hwei-Fen. Nyonya Needlework: Embroidery and Beadwork in the Peranakan World. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2017.

Cheah, Hwei-Fen. Phoenix Rising: Narratives in Nonya Beadwork from the Straits Settlements. Singapore: National University Press, 2010.

Endon, Datin Seri. The Nyonya Kebaya: A showcase of Nyonya kebayas from the collection of Datin Seri Endon Mahmood. Malaysia: The Writers’ Pub. House Sdn Bhd, 2002.

Ho Wing Meng. Straits Chinese Beadwork and Embroidery. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2008.

Huang Lijie. “Nyonya embroidery and beadwork on show at the Peranakan Museum”, The Straits Times, 28 June 2016.

Lam, Shusan. “Defiantly, he weaves life into a dying Peranakan craft”, Channel News Asia, 22 June 2016.

Lee, P. Sarong Kebaya. Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2015.

Lee, Su Kim. “The Peranakan Associations of Malaysia and Singapore: History and Current Scenario”, Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 82(2): 167-177, 2009.

Lee, Thienny. “Dress and Visual Identities of the Nyonyas in the British Straits Settlements; mid-nineteenth to early-twentieth century”,The Sydney eScholarship Repository, 2016, https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/15900. Accessed 21 June 2018.

Png Poh-Seng. “The Straits Chinese in Singapore: A Case of Local Identity and Socio-Cultural Accommodation”, Journal of Southeast Asian History 10(1): 95-114, 1969.

Rudolf, Jürgen. Reconstructing Identities: A Social History of the Babas in Singapore. Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998.

Shaw, J. & Ismail, R. “Ethnoscapes, entertainment and heritage in the global city: segmented spaces in Singapore’s Joo Chiat Road”, GeoJournal 66(3): 187-198, 2006.

Tan, Guan. “The Last Two Peranakan Kebaya Makers in Singapore”, The New York Times Style Magazine Singapore, 19 April 2017.

The Peranakan Association. “Beaded Beauties: The Kasut Manek”, The Peranakan, 1997, https://www.peranakan.org.sg/magazine/1997/1997_Issue_2.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2018.

Tong, Lillian. Straits Chinese Embroidery and Beadwork. Penang: Phoenix Press, 2015.