Chinese New Year

One of the most important festivals for Chinese communities, Chinese New Year encompasses a vibrant and diverse range of practices and traditions. Chinese New Year is based on the Chinese lunar calendar and falls on the second new moon after the winter solstice. The celebrations last for 15 days, and reinforce cultural values such as family harmony, social relations and securing good fortune for the coming year. It is time for visiting family and friends, with the ritual exchange of traditional gifts of money and symbolic foods.

There are different myths surrounding the origins of the festival, one being an ancient sacrificial rite called la ji (腊祭) held to give thanks to the gods and pray for more plentiful harvests ahead, and another being the legend of nian (年), a mythical beast that was driven away by loud noises and bright red colours that is characteristic of the festival.

Geographic Location

Chinese New Year is celebrated around the world by Chinese communities. The celebrations take place in households when families and friends visit relatives’ and friends’ houses, and at workplaces where lunches or dinners may be hosted.

In Singapore, the festivities extend to markets, fairs and public performances, such as the Chinatown bazaars, the River Hongbao along Singapore River, and Chingay Parade along the streets of Singapore.

Communities Involved

In Singapore, the Chinese community celebrates the Chinese New Year, within households and at work places. Organisations, such as business and clan associations, the People’s Association and various community groups also play a major role in organising and hosting various communal festivities.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

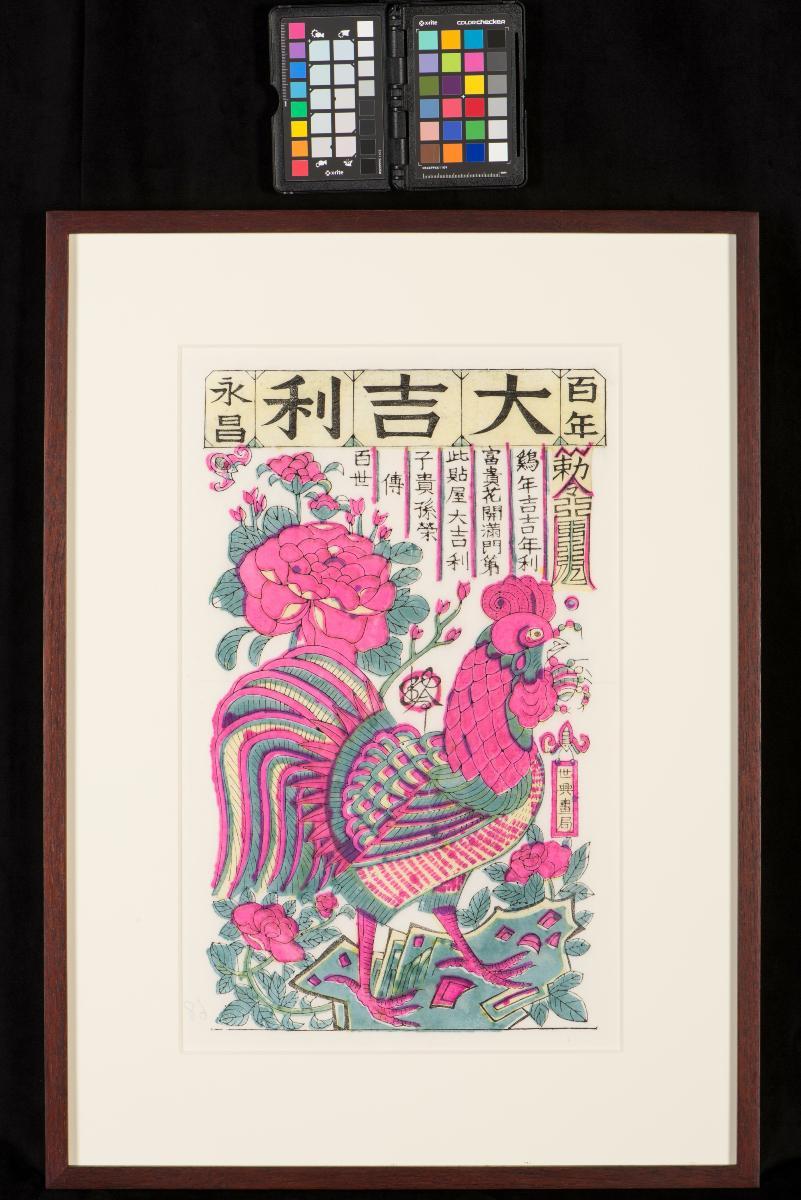

Prior to the start of Chinese New Year, many Chinese families will spring clean their households. The Chinese word for “dust” is chen (尘), which is homophone for the word “old”. Hence, the act of cleaning and sweeping away dust is symbolic of getting rid of bad luck and old things to usher in the new year. Families would also put up decorations around the house, such as spring festival couplets (chun lian, 春联), red paper cuttings with auspicious words that symbolises prosperity (fu, 福), and plants such as the pussywillow (yin liu, 银柳) which is believed to bring in wealth. Many Chinese families will also buy new clothes to wear on the actual day of Chinese New Year, and stock up festive foods.

Chinese New Year remains relevant and thriving in Singapore because it reinforces the traditional Chinese understanding of family and social relations. For many families, Chinese New Year is an opportunity to demonstrate their awareness and adherence to Chinese values. For example, on the first morning of Chinese New Year, children pay their respects to their elders in the household. This is followed by visiting their relatives’ or friends’ houses to exchange New Year greetings and gifts. The younger generation offers greetings with a pair of oranges. The older generation reciprocates with good wishes and a “red packet”, which is a decorative envelope containing a token amount of money. Red packets are given by married persons, regardless of age. Singapore also observes a number of practices that are particular to the region or which reflects practices of southern Chinese origins. For example, it is customary to offer the host a pair of mandarin oranges when visiting and to receive another pair in return. This practice is believed to be linked to the Chinese name for mandarin oranges which is a homonym for “luck in abundance” while the Cantonese pronunciation of mandarin orange (gan, 柑) sounds like gold (kam, 金).

The reunion dinner, also known as tuan yuan fan (团圆饭) is a highlight of the festival and remains a significant event for most families. It symbolises the reuniting and coming together of family, and carries an over-arching theme of looking towards the new year with hope. The dinner is held on Chinese New Year’s eve, and usually involves the extended family gathering at the household where the patriarch resides. The meal is often lavish in its variety, and dishes bear symbolic, auspicious meanings. After the meal, the family traditionally stays up together until after midnight to usher in the New Year.

Food is an important aspect of the Chinese New Year festivities. An essential dish enjoyed only during Chinese New Year is yusheng (鱼生), a raw fish salad which means “abundant life” and custom of tossing and reciting auspicious phrases (lo hei, 捞起), and is popular to Singapore and Malaysia. The dish is elaborate and colourful, and has a wide variety of vegetables, raw fish or sliced abalone. The practice of lo hei is widespread in Singapore, and is eaten within families or at large events, where non-Chinese also partake in the practice, along with friends and colleagues. Another popular food item consumed during Chinese New Year is bak kwa (肉干), barbecued meat slices that have a sweet and smoky flavour prepared by grilling it over fire.

Chinese New Year is also a time for employers and leaders of social and community groups to demonstrate their benevolent patronage. For example, the seventh day of Chinese New Year is known as the “birthday of mankind”. Employers usually take this time to show their appreciation to employees by holding lunches or dinners. Another staple celebration during the festival is the tuan bai (团拜), which literally means “gatherings to exchange greetings”. These gatherings are mostly organised by Chinese clan associations and usually involve dinner, which is very much a part of the communal life of constituents and grassroots organisations.

Experience of a Practitioner

The customs and traditions associated with Chinese New Year continue to be practised by many families, including the family of Mr Samuel Tan, who is of Hock Chew (also known as Foochow) dialect. Mr Tan’s family puts in much effort and thought when it comes to preparing food for the celebrations. His parents will usually prepare hong zhao ji (红糟鸡), a dish of chicken stewed with red yeast lees, and Foochow fishballs filled with mincemeat. He also makes his own yusheng. When it is time to eat the salad, his family will gather to toss and mix the ingredients while uttering good wishes and blessings for the New Year. To Mr Tan, the significance of the yusheng is not in the colours or the food itself. For him, it is about gathering as a family and enjoying the experience in preparing and consuming the dishes.

Watch: Chinese New Year

Present Status

Like Mr Tan, many families continue to celebrate Chinese New Year, which continues to be one of the most important Chinese festivals celebrated in Singapore. The widespread celebrations associated with the festival ensures that the traditional values continue to be passed down to the younger generations, and that the core meaning of Chinese New Year is not forgotten.

References

Reference No.: ICH-021

Date of Inclusion: April 2018; Updated March 2019

References

Chew Seng Kim. “A familial feast.” The Straits Times, 24 January 2009.

Gai Guoliang. Exploring Traditional Chinese Festivals in China. Singapore: McGraw-Hill Education (Asia), 2009.

Leong Weng Kam. “The strong pull of River Hongbao.” The Straits Times, 14 February 2010.

Leong Weng Kam. “Tuan bai.” The Straits Times, 5 February 2011.

Leong Weng Kam. “18 years on, Spring still shines in the City.” The Straits Times, 6 February 2011.

Sim, Bryna. “CNY customs: Take the test.” The Straits Times, 2 February 2014.

Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations. Chinese Customs and Festivals in Singapore. Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations, 1989.

Welch, Patricia Bjaaland. Chinese New Year. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1997.