Text by Choo Meng Kang

MuseSG Volume 11 Issue 1 - 2018

Singaporeans identify with Pasir Ris in different ways. For the many residents who live in Pasir Ris, the town is home. But to others, it is a place filled with memories of Basic Military Training where Singaporean sons shared hugs of greetings and goodbyes with their families and friends. Most Singaporeans, however, would associate Pasir Ris with a place to unwind and take a break from the mundane and hectic routines of school and work by enjoying the town’s coastal chalets, water theme park and beachfront. The unique history of Pasir Ris, and its identity as a beachfront town for rest and recreation have shaped its development and defined its unique character in the collective memory of Singaporeans.

Origins: “Sand to Be Shred”

The first mention of Pasir Ris dates back to 1844 in land surveyor John Turnbull Thomson’s map, where its name was spelled “Passier Reis”.1 The name Pasir Ris is possibly a contraction of the word “Pasir Hiris” (in Malay, Pasir means “long sand” and Hiris means “to shred or slice”).2 This likely indicates that the locale was named after its sandy beach front.

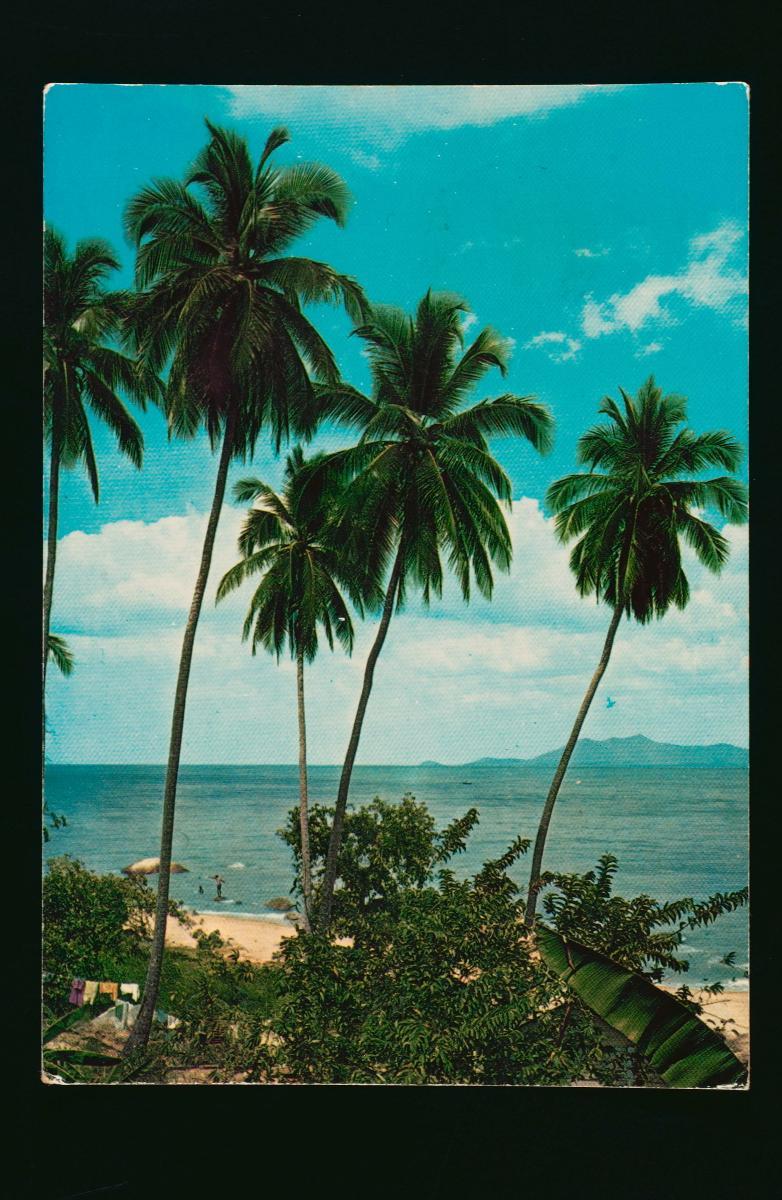

The early Pasir Ris villages, such as Kampong Loyang and Kampong Pasir Ris, were all centred on agriculture and livestock farming, and these were the mainstay activities in the district in the early-19th century.3 This, however, changed in the 1890s when Jewish broker Ezra Nathan and real estate agent H. D. Chopard built country homes meant for rest and recreation in Pasir Ris. Chopard’s bungalow, priced at $2 per day, had sea bathing and fresh water as its key selling points. Its popularity, however, is unknown.3 Similarly, Nathan’s bungalow in Pasir Ris was also utilised for celebrations and recreation, though specifically by the Jewish community.5 The establishment of these holiday bungalows by the beach in the 19th century marked the beginning of Pasir Ris’ recreational nature.

Early Development of the Beach Front

After the establishment of these bungalows, Pasir Ris soon gained a reputation as a retreat space for the upper echelons of Singapore’s society. For instance, wealthy businessman Teo Kim Eng often hosted gatherings for the Useful Badminton Party, a reputable badminton club, at his Pasir Ris bungalow.6 Newspaper advertisements also illustrate Teo’s bungalow being used for picnics for the Straits Chinese Methodist Youth Fellowship.7

However, getting to Pasir Ris was a difficult challenge. To approach Pasir Ris from the city centre, one had to travel the length of Changi Road before turning west down Tampines Road for many miles. For Teo’s events, transportation for participants even had to be arranged and announced on the newspapers.8 Compared to the easily accessible south-eastern coastline stretching from Tanjong Katong to Changi (present-day East Coast area), Pasir Ris was a much less desirable location.9 The inaccessibility of Pasir Ris perhaps explains why there are scant records of new seaside bungalows being built there between the 1910s and 1930s.

The 1950s: Further Expansion

After a pause during the Japanese Occupation, a number of new developments commenced on the Pasir Ris beachfront. The popularity of the beach and the demand for recreation in the post-war years gave private investors an incentive to develop a resort hotel there. One such development was the former Pasir Ris Hotel, which opened on 17 May 1952 at 143 Elias Road, off the 10th milestone of Tampines Road.10 However, like the earlier retreat houses, the recreational facilities at Pasir Ris Hotel were open only to a select group of people. In May 1959, the hotel was taken over by the British Royal Air Force (RAF) and used exclusively for their personnel and families. This resulted in quite a stir during an incident where Hong Kong star Ting Lan was denied service from the hotel staff after her filming.11 Such incidents aptly reflect how Pasir Ris was a popular recreation destination only for colonial administrators and the affluent, at least until the mid-1950s.

Nevertheless, efforts to develop Pasir Ris as a town for recreation and leisure were not just relegated to the private sector, and state-initiated efforts eventually opened up the beach for greater public use. In 1958, the state-run Singapore Rural Board developed the beaches at Changi and Pasir Ris. Then Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock officially opened facilities at Pasir Ris beach in August 1958, claiming they were “available to everyone on the island”.12 The development saw the building of a promenade, the installation of shelters and seats, as well as the construction of a sea wall.13 Shortly after the opening, the Singapore City Council planned a giant picnic at Pasir Ris beach for 5,000 of its employees and their family members. Ninety buses and four hundred cars were activated to transport the employees, while 50 hawkers were given special permission to set up food stalls.14 These forms of government endorsement helped Pasir Ris to gradually shift its public image from an elitist recreation destination to a more inclusive one.

This combination of government and private initiatives reinforced Pasir Ris’ identity as a resort- like recreational town. In the 1950s and early 60s, Pasir Ris beach became a go-to place for the hit recreational activity of the time – water skiing. The sport attracted people from all walks of life, including British Commissioner General of Southeast Asia Malcolm MacDonald who participated in a water ski gala there in 1955.15 Additionally, the Malayan Water-ski Association also held numerous water-skiing competitions and galas at Pasir Ris Hotel. These competitions were held every two months at Pasir Ris, and became a spectacle of fun for both competitors and patrons of the beach.16

Post-1965: Towards the Building of a Residential Town

Although there were developments on the beachfront, the residential area and villages of Pasir Ris remained largely untouched. Up until the 1960s, only poultry farmers and fishermen lived in Pasir Ris.17 After Singapore’s independence in 1965, plans were made to spruce up the area. This included the building of two community centres in 1966: Pasir Ris Village Community Centre at the 11th milestone of Tampines Road and Kampong Loyang Community Centre at the 13th milestone of Tampines Road.18 These centres became communal spaces that allowed residents to interact and bond over recreational activities such as holiday camps, or classes where residents could learn cooking, ballet, piano, guitar and cake-making.19

In 1974, a private housing company, Kong Joo Pte Ltd, built over 300 bungalows and semi-detached houses around the area of Pasir Ris Hotel.20 Unfortunately, due to a housing slump, the state’s Housing & Urban Development Company (HUDC) decided in late-1974 to buy over the unsold terrace houses and resell them at a cheaper price to middle-class citizens.21 Initiatives such as these contributed to the expansion of residential areas. These new residents increased the number of people living in Pasir Ris, which formerly comprised long-time village residents who continued to live in Kampong Loyang and Kampong Pasir Ris until the 1980s, when they were resettled into the nearby residential towns.22

Meanwhile, activity on the beachfront was going strong. In 1971, the People’s Association built several multi-storied holiday flats catering to income groups of all levels.23 This was a departure from the days when the options of private bungalows, villas and Pasir Ris Hotel could only be afforded by companies, institutions or the wealthy. These holiday flats built by the People’s Association further added to Pasir Ris’ transformation from a largely private leisure space to an all-inclusive holiday town.

As for the eponymous hotel, after RAF’s exclusive contract ended in 1966, Pasir Ris Hotel was once again opened to the public. Reportedly though, it never quite “regained its former popularity”.24 This eventually led to a change in management in 1974, with Paul Lim taking over as general manager.25 He embarked on a re-branding effort of the hotel with an emphasis on leisure by the beach and sea. The hotel advertised scenic surroundings, modern sanitation and barbecue pits, and offered boating, dancing and swimming to guests and the public. It even had a tag line: “After a week in the city, we know just what you need”.26

With the need to house Singapore's growing population, the Housing & Development Board (HDB) began land reclamation works along the coast of Pasir Ris in 1979 with the aim of building a new residential town.27 Upon the completion of Pasir Ris Town in 1988, population density was growing in tandem with the development of new recreational spaces.28 The establishment of spaces such as the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) holiday resorts, NTUC Downtown East and Wild Wild Wet facilitated Pasir Ris’ sustained reputation as a location for recreation. The NTUC holiday resorts officially opened in 1988 as the largest seaside resort in Singapore, with 396 chalets that could accommodate 1,600 holiday- makers each day.29 In 2004, it underwent a revamp and was renamed NTUC Downtown East. Renovations cost $65 million and two theme parks were added into its list of attractions. These included the Escape Theme Park (closed in 2011) which featured high thrill adventure rides and Wild Wild Wet – a water theme park.30 An entry by Ronnie Ang, as part of the Singapore Memory Project, typifies patrons’ memories of Downtown East as a hub for recreation:

Downtown East is the recreation complex in Pasir Ris. With cinemas, bowling alley, shopping centre, supermarket, restaurants, children’s playgrounds, entertainment marquee, water theme park and a hotel. A place any one at any age can go to relax.31

Company retreats, birthday celebrations and class gatherings during school holidays became the mainstay reasons for the usage of these recreational spaces. Contrasted to Sentosa Island, which had become an increasingly expensive tourist destination, Pasir Ris provided Singaporeans with a cheaper alternative for recreation. An online post on TripAdvisor made by user Willy Lim echoes such a view:

The rear side of the [Downtown East] chalets is Pasir Ris beach. You can go cycling or spend some time at the beach. Consider it as a more budget friendly alternative to a Sentosa staycation.32

Aside from recreational spaces being constructed, the building of a bus interchange in 1989 and the White Sands shopping centre in 1994 also contributed towards the urbanisation of Pasir Ris.33 These two spaces are significant to the memories of numerous Singaporean families. With the opening of the new Basic Military Training Centre (BMTC) in 1999 on the island of Pulau Tekong, located north-east of Pasir Ris, Pasir Ris Bus Interchange had become a fall-in and drop-off point for BMTC recruits.34 Families and friends would often have a meal together nearby before heading to the Basic Military Training fall-in area located within the sheltered walkways of the bus interchange. In an interview with NSman Chia Tai Wei Eugene, he recounts:

Whenever it was time to book in, I would have a meal with my family at White Sands before bidding them farewell at the fall-in area at the interchange.35

Such private moments are part of the collective memory that Singaporeans have of White Sands shopping mall and the bus interchange. These two spaces not only provide Singaporeans with opportunities for recreation, but also give families and friends an opportunity for heartfelt goodbyes and joyful reunifications. By partaking in these activities, Singaporeans unknowingly associate Pasir Ris with emotions of enjoyment and social bonding. This consequently ascribes to Pasir Ris the reputation of a recreational hub which is today embodied by numerous recreation sites – a testament to its longstanding, living heritage.

Present Day: An Enduring Heritage Shaped by Surrounding Sands

Since the 1880s, the identity of Pasir Ris has always been centred on the notion of a beachfront locale built for recreation and leisure. This legacy is reflected through the ocean-themed architectural designs of playgrounds and parks such as the Atlantis Park and the Bumboat Playground off Elias Road.

Today, Pasir Ris continues to retain its resort-like ambience even amidst its redevelopment as a residential estate. This atmosphere is continually reinforced by urban developers selling the dream of beachfront living, just as Pasir Ris Hotel once did. Whether such an identity will endure the test of time depends on the waves of new residents that now call Pasir Ris home. Nevertheless, whether you think of Pasir Ris as a beach front resort, or as a home by the beach, one thing is for certain: Pasir Ris’ heritage has always been shaped by the sands that surround it.