Text by Ruchi Mittal

MuseSG Volume 10 Issue 1 - June 2017

Little India is a precinct that is not quite like any other in Singapore. Together with Chinatown and Kampong Glam, it is part of the popular trio of cultural precincts on the tourist circuit. It is also an important place for the local Indian community who visit it to eat, shop, socialise and pray.

Today, it has come to be known as the Indian precinct, but this was not always the case. In fact, Little India was not designated by Sir Stamford Raffles as an area for the Indian community in the Raffles Town Plan. Before Little India got its current name in the 1980s, it was just known as Serangoon, after one of the earliest roads in Singapore. This road was indicated on an 1828 map as the “road leading across the island”.

An Important Thoroughfare: 1819 to 1860

Serangoon Road got its name from the Malay word saranggong. It is likely that this derived either from a marsh bird called ranggong or the term serang dengan gong, which means to beat a gong. It began as an important artery of commerce and transport for the plantations in the interior of the island along the route to Serangoon Harbour. This northern harbour was never a major port of call for Singapore’s entrepôt trade. However, it was a vital loading and unloading point for the Johor gambier and pepper planters. These goods would then be transported to town by bullock carts.

Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore.

The road remained a buffalo-trodden dirt track for many decades. In the 19th century, the opportunities available in Serangoon drew various communities there. Possibly, the most important factor for this was the presence of waterways. The Kallang and Rochor rivers facilitated habitation, transportation and commerce.

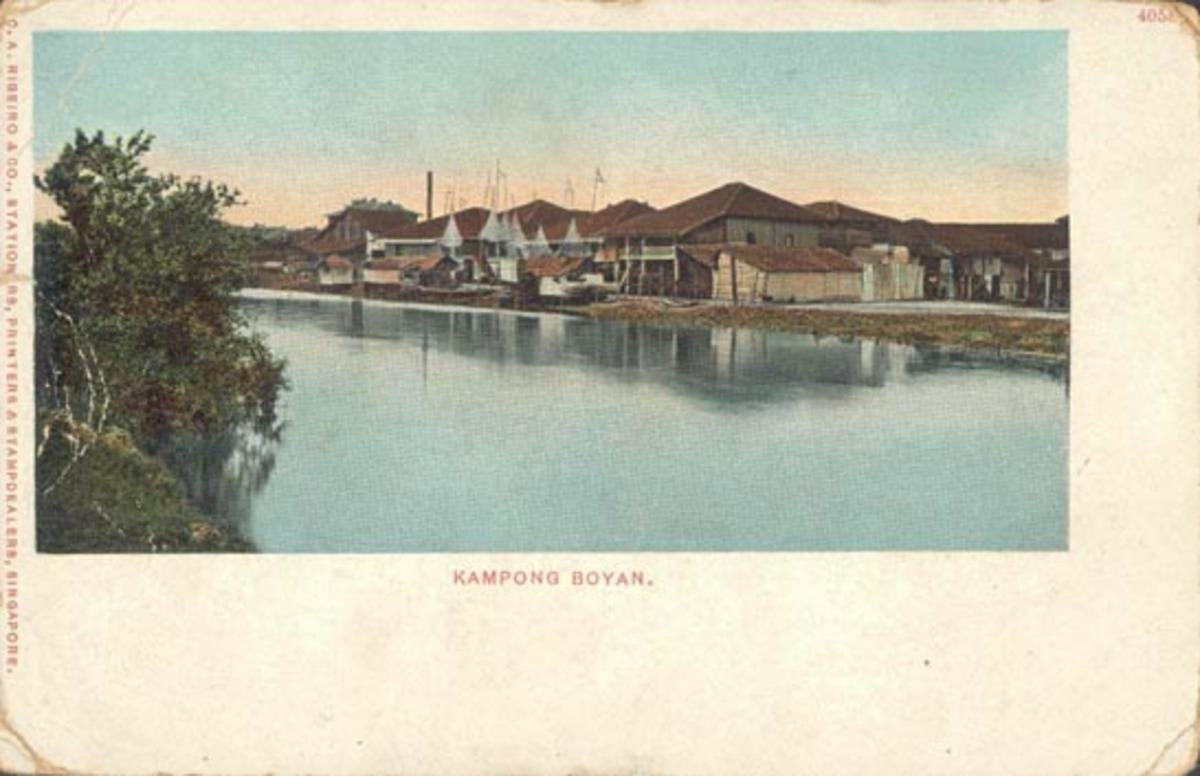

For these reasons, many kampongs (Malay for “villages”) were established around the Serangoon area. The Chinese community congregated around the present-day Syed Alwi Road and Balestier Road areas, and were largely involved in farming and plantation activities. The Javanese lived at Kampong Java, while the Baweanese established themselves at Kampong Kapor, many of whom worked at the nearby racecourse.

Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore.

Kampong Kapor also attracted Indian Muslims, who worked mainly as port labourers and peons (low-ranking office workers).

Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore.

Serangoon Road proper was laid by convicts who had been brought to Singapore by the British for their labour and were held at a prison at Bras Basah Road. Many of them settled nearby after serving their sentences.

Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore.

Other Indians also gathered in that area to practice supporting trades. This was the genesis of an Indian district, which later extended down Selegie Road and into Serangoon Road.

Indians called the Serangoon area Soonambu Kambam, meaning “Village of Lime” in Tamil. In the past, lime was an important ingredient of Madras Chunam. This was a kind of cement or plaster brick that was introduced from India and used in construction work. By the 1820s, the British set up lime pits and brick kilns along Serangoon Road, where many Indians found employment.

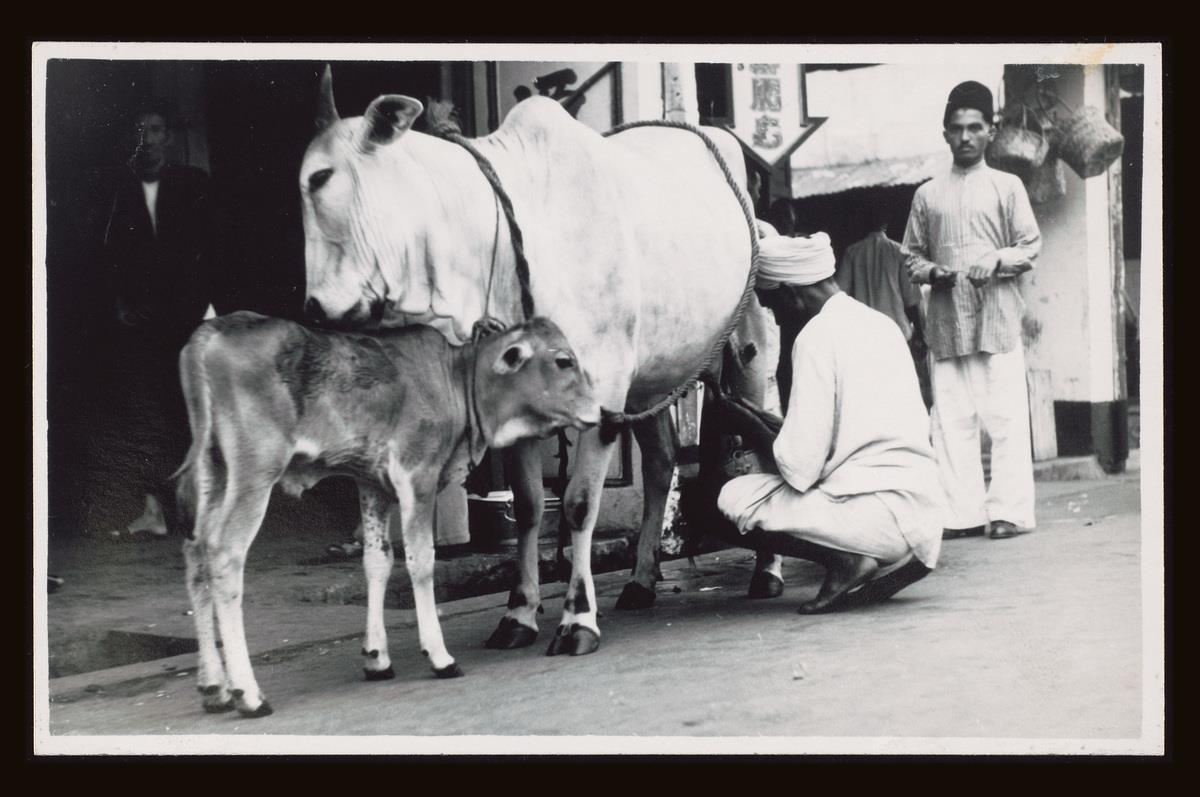

An Era of Cows and Buffaloes: 1860 to 1930

The brick kilns were discontinued in 1860. After this, the development of the Serangoon area centred on cattle, which transported produce to town for sale. This area was ideal for cattle because of the abundant water from ponds, mangrove swamps and Rochor River. These provided bathing areas for water buffaloes, which were the workhorses of Singapore at that time and were used for all heavy tasks, from transporting goods to rolling roads.

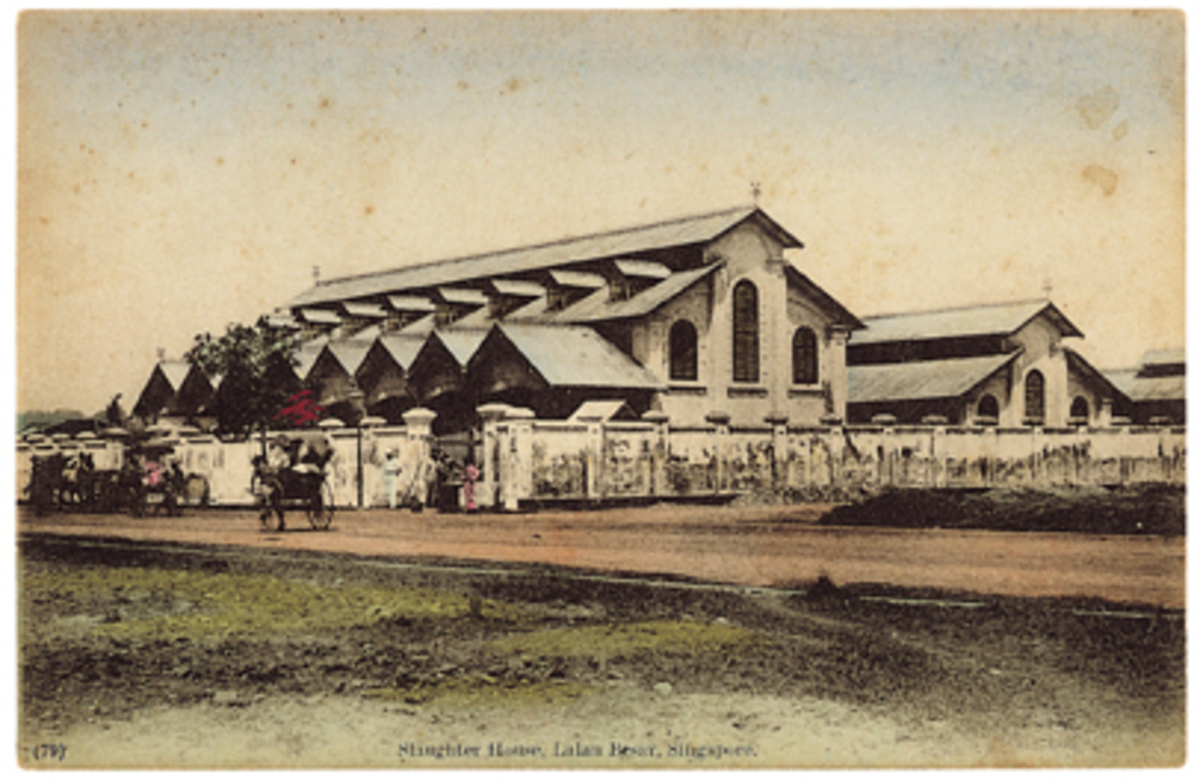

Many cattle-related industries were established in and around Kandang Kerbau (Malay for “buffalo enclosure”). This village was located to the west of Serangoon Road and later became known as Kampong Kerbau. Such industries included slaughterhouses, tanneries and milk peddling.

Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore.

The presence of the cattle industry attracted even more Indian settlers such as North Indian herdsmen from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar in the early 1900s who settled by Rochor Canal. Until the 1930s, one could also find Bengali and Tamil milkmen around Buffalo Road and Chander Road. They travelled with their goats and cows, bringing fresh milk right to customers’ doorsteps. Another common sight was Indian women travelling from house to house, selling fresh homemade thairu (Tamil for “yoghurt”).

Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore.

The old Tekka Market was built in 1915 at the junction of Serangoon and Bukit Timah roads as one of the first centralised sites for selling cattle produce. An important reason for building this market was so that the retail activities did not clutter up the verandas and roadways along Serangoon Road.

S. Rasoo, a former watchman at Tekka Market, remembers it as a “lively, bustling place with Indian women coming up in their colourful saris, their hair done up in buns or single plaits decorated with fragrant flowers, jostling against the pig-tailed houseboys that served the Europeans and wealthy Asians. The noise was deafening, the atmosphere reverberating with the sound of raised voices bargaining over fresh fish, meats, vegetable and fruits”.

Courtesy of National Heritage Board.

Multicultural Centre of Business and Trade: 1860 to 1970s

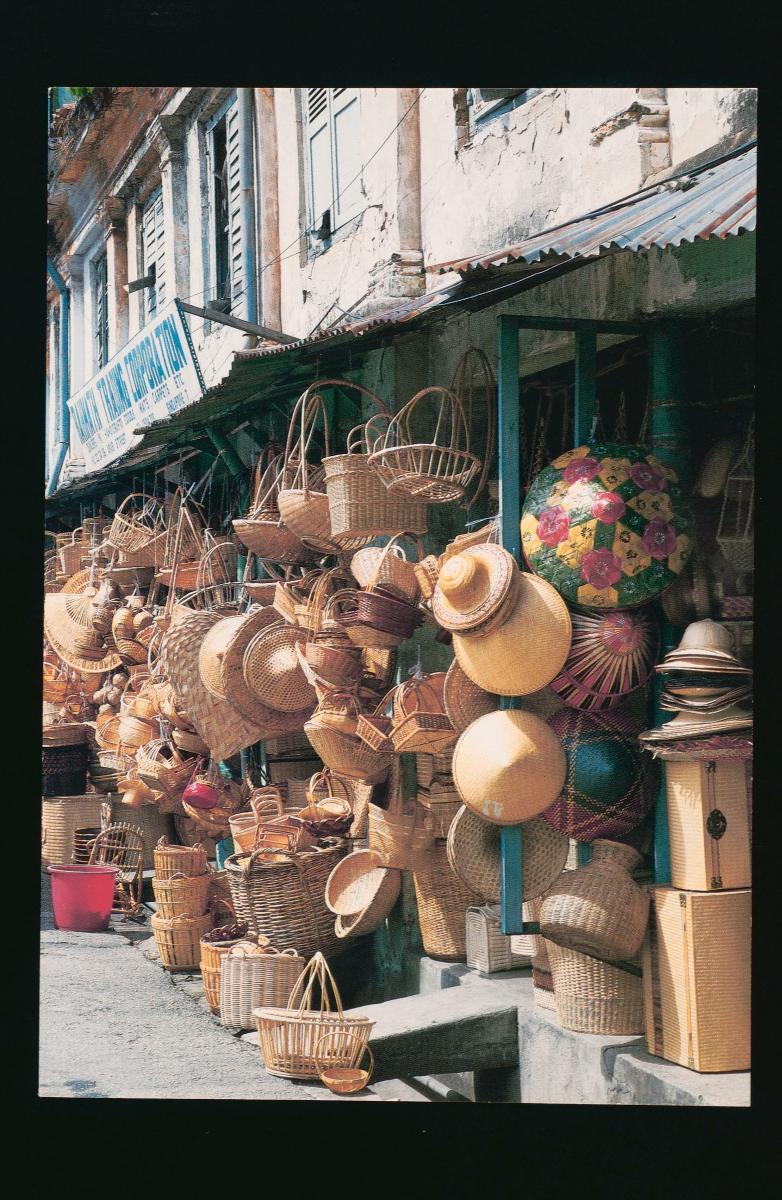

Wheat-grinding sheds, sesame oil presses, rattan works, rubber smokehouses and pineapple factories emerged alongside the cattle industry. Although these industries may seem unconnected, they had a symbiotic relationship centred on the wet environment with buffaloes providing the labour. Their waste products were often used as cattle feed.

One such example was taukeh (Malayan term referring to a Chinese businessman of good standing) Tan Teng Niah’s sweet factory at Kerbau Road which used sugarcane to manufacture candies. It is likely that the bungalow which can still be seen today was part of this factory.

Courtesy of National Heritage Board.

Sugarcane was transported to Tan’s factory by bullock carts, and after the juices were extracted, the leftover fibres were reused as fuel or cattle feed.

There was a significant Chinese and Malay presence in the Serangoon area at the beginning. However, various factors helped to eventually establish a larger Indian enclave here. For instance, many Indian migrants were employed by the municipality in the early 20th century. From the 1920s, the colonial government started constructing terrace houses in Serangoon to accommodate them. These were known as Municipal Quarters or Coolie Lines. Some of these quarters can still be found in their original form along Hindoo Road in Little India.

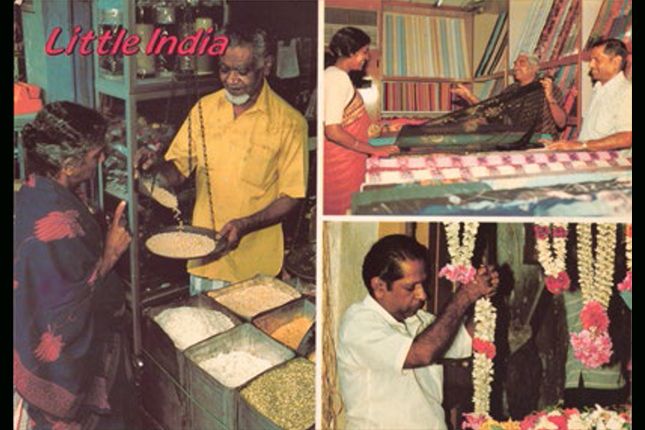

Shops and amenities catering to this growing Indian population flourished. There were garland makers, astrologers, goldsmiths, moneylenders, tailors, restaurateurs and shop owners selling luggage, saris, spices and other provisions from India.

Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore.

The Turmoil Brought by World War II: 1941 to 1945

When the Second World War began, Serangoon Road became one of the targets for Japanese bombers. Kannusamy s/o Pakirisamy (b. 1914) used to live at Buffalo Road as a child. Speaking to the National Archives of Singapore, he recalled: “... some houses were damaged by bombs in front of Hindoo Road and... [in] Farrer Park, some people went and put camps. [...] The Japanese bombs [would] be coming three, six, nine, in V-shape. [...] Houses were all damaged.”

Many people turned to places of worship for refuge at this uncertain time. The Sri Veeramakaliamman Temple was one such place where hundreds took shelter. It survived unscathed through the bombing and this was attributed to the power of the deities by its devotees.

Courtesy of National Heritage Board.

However, other sanctuaries were not as fortunate and one side of Foochow Methodist Church was destroyed. Another casualty was Kandang Kerbau (KK) Hospital, where a big red cross was displayed so that it would not be bombed.

Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore.

Unfortunately, one morning the British began moving their lorries and guns into the compound and the hospital was bombed within half an hour.

At this time, Singapore’s second president, Dr Benjamin Sheares (1907 to 1981), was Deputy Medical Superintendent at KK Hospital. As there was only one other doctor at the hospital, both men stayed there and worked in shifts. Midwives were also kept very busy as there were only three nurses to look after around 200 babies.

When the smoke cleared in February 1942, Singapore had become Syonan-To. It is believed that the conquering “Tiger of Malaya”, General Yamashita himself, passed through Serangoon Road. During the first weeks of the Japanese Occupation, New World Park in Serangoon was one of the 28 sites used as a mass-screening centre for the Dai Kensho (Japanese for “great inspection”) operation to remove anti-Japanese elements within the Chinese population of Singapore, later known as the Sook Ching (Mandarin for “cleansing through purging”) massacre.

The Urbanisation of Serangoon Road: 1945 to 1980s

Even after the war ended in 1945, its effects on Little India’s socio-economic landscape remained. Many shop owners had sold their businesses to their hired hands before they fled the island. Those who survived moved up the social ladder in the post-war era.

P. Govindasamy Pillai, affectionately known as PGP, had five sari shops in Serangoon before World War II. He left for India in 1941, handing his business to a relative. He returned after the war to continue his business. While new businessmen were just setting up in the 1960s, PGP was already moving ahead and renovating his existing stores. He was also known for his generosity in using his wealth for philanthropic purposes and supporting community institutions such as temples.

Courtesy of Urban Redevelopment Authority.

Once Singapore attained full independence in 1965, there was a drive to clean up and renew the city. Early efforts focused mainly on the town area and later expanded outwards to encompass Serangoon. At this time, many residents of this area were living in dark, cramped and unhygienic conditions. By the mid-1970s, concrete development plans had been introduced with the Housing & Development Board (HDB) setting aside a significant sum of S$4 million for Kampong Kapor’s renewal.

In 1980, it was decided that the old Tekka Market had to be relocated to a better facility nearby. The Zhujiao Centre (now Tekka Centre) was thus built across the road in 1981. It was planned as one of the early residential-cum- shopping complexes in Singapore and included a wet market, food centre and HDB homes.

Serangoon becomes Little India: 1980s to Present Day

Little India as we know it today was not officially named as such until the 1980s. This was the result of a concerted effort by the then Singapore Tourist Promotion Board (STPB) to promote the preservation and celebration of Singapore’s ethnic quarters.

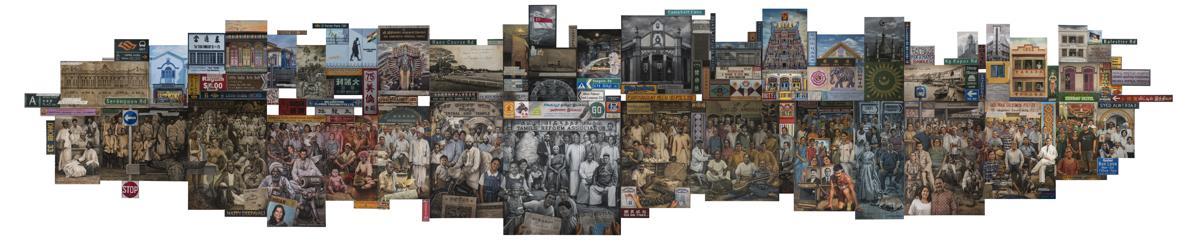

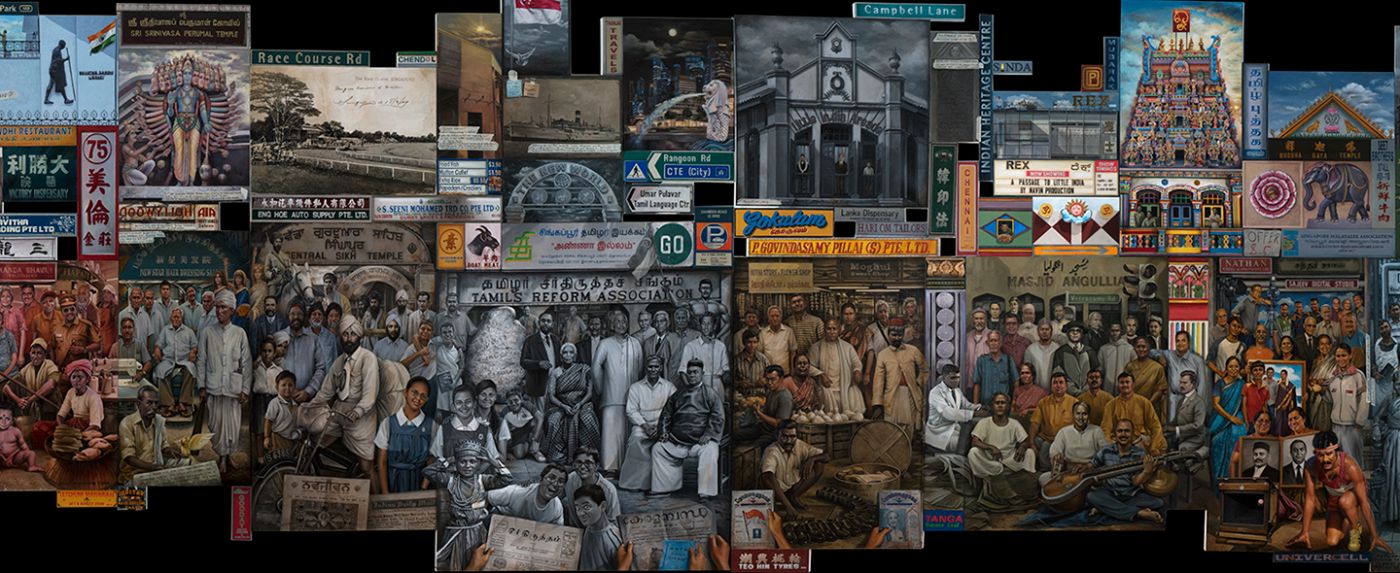

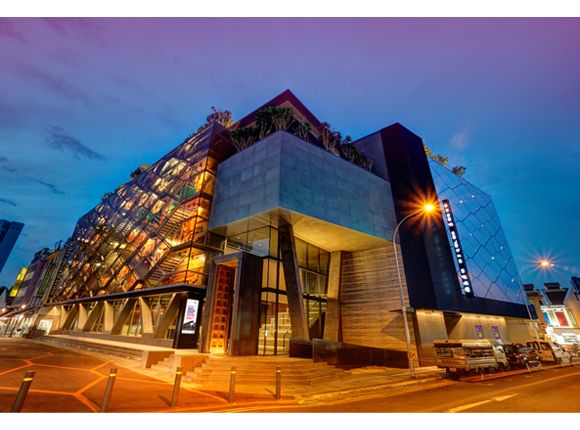

Today, Little India is a district that offers something for everyone. While local Indians visit the temples here and shop for traditional goods, non-Indian locals and tourists also come to soak in the culture and history of this historical precinct. Launched in 2017, the Little India Heritage Trail reveals some of the stories and memories of this area, while offering three thematic routes for visitors to better understand this area.

Courtesy of Urban Redevelopment Authority.

Go on the Little India Heritage Trail!

The Little India precinct melds the old with the new and hosts trades from the past alongside modern businesses. Through three thematic trails, discover the rich and diverse histories, cultures, religions and trades in this colourful historic precinct.

Visit the online version of the trail here.