Text by Suhaili Osman and Muhammad Qazin Abdul Karim

Be Muse Volume 7 Issue 3 - Jul to Sep 2014

Singapore prides itself on its multicultural society and the resultant cultural diversity that such a multi-ethnic social landscape produces. Nonetheless, historical official categories of ‘race’ and ‘ethnicity’ in singapore have tended to gloss over the rich heritage and cultural practices unique to sub-ethnic groups within the larger ethnic ‘wholes’. Hence ethnic categories such as ‘Chinese’, ‘Malay’ and ‘Indian’ may only scratch the surface of cultural communities that are in fact far more complex, with myriad histories and customs, despite some shared religious practices and languages.

In that respect ‘Malay’ sometimes becomes a convenient administrative ‘shorthand’ – a catch-all term that belies the various origins and social histories of the Malayo-Polynesian communities of Southeast Asia, communities which include diverse groups such as the Baweanese, the Javanese, the Minang, the Bugis, the Banjarese and the Mandailings. For centuries, these peoples voyaged back and forth across what historian Leonard Andaya has termed the ‘Sea of Melayu’ and many of them, especially the Baweanese, came to settle in Singapore during the period of European colonialism in the 19th-20th centuries.

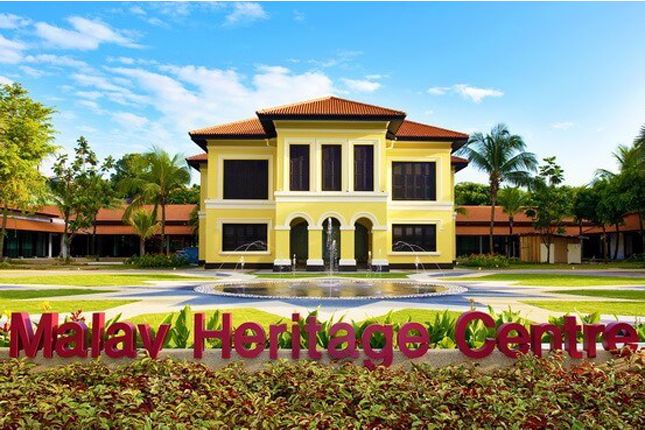

On 15 March 2014, the Malay Heritage Centre (MHC) launched its first-ever community co-curated exhibition, LaaobeChanging Times: Baweanese Heritage & Culture in Singapore (Laaobe: Warisan & Budaya Bawean di Singapura). The exhibition, which featured the Baweanese community in Singapore, also marked the launch of the Se-Nusantara series. This is another exhibition put up annually that features a different sub-ethnic group of the Malays in Singapore. Each partner sub-ethnic cultural group will get to work together with MHC’s curatorial experts to showcase their unique cultures and tell their diasporic histories of merantau (voyaging) across Southeast Asia, and how they ultimately came to compose the mosaic of Malay identities in Singapore.

Laaobe highlighted the Baweanese community in Singapore, whose forefathers hailed from Pulau Bawean, a small island located off the northeastern coast of Java. Laaobe, which means “changed”, showcased the heritage and transformation of the local Baweanese community over the years, as shaped through various historical and socio-economic events.

The exhibition presented the history and development of Singapore’s Baweanese people through over 40 objects and archival materials contributed by the community. Exhibits included rarely-seen personal collections of pictures of ponthuk life and daily objects found in Baweanese households, such as handwoven pandan mats and bags, and a high-footed bed frame popular with Malay families in the past.

Who are the Baweanese?

Narratives of diasporic communities usually revolve around several themes and milestones in their journey and experiences in their new homeland. They usually elaborate on the reasons the Baweans migrated to Singapore, factors that contributed to their migration patterns, and the impact of their migration on Singapore’s cultural landscape. The exhibition sought to provide an insight to these topics and introduce both local and foreign visitors to the MHC to the vibrant Baweanese community in Singapore. The Baweanese originated from a small island called Pulau Bawean, which is located off the northeastern coast of Java in modern-day Indonesia. The inhabitants call themselves ‘orang Phebiyen’ or ‘orang Bawean’, speak ‘Baweanese’ and profess Islam as their faith. Here, they are more familiarly known as Orang Boyan (‘Bawean people’, although ‘Boyan’ is a mispronunciation of ‘Bawean’).

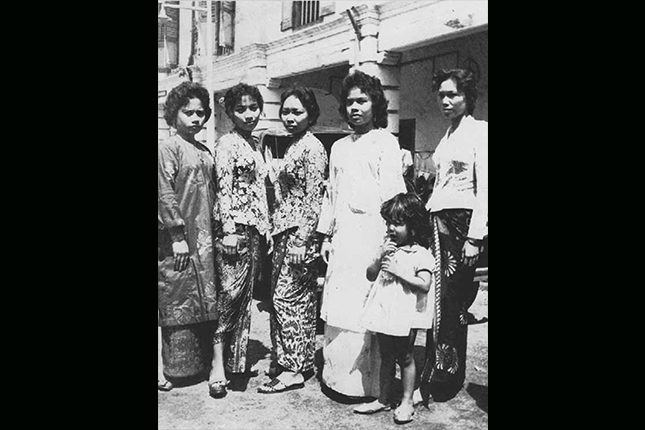

Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore.

Merantau and the Malay Diaspora in Souteast Asia

Merantau, the Baweanese cultural practice of temporarily migrating to distant lands in search of work opportunities and to better oneself, was one of the key factors that led to scores of young Baweanese men leaving their ancestral desa (villages) in search of their fate and fortunes. The majority did not have the intention to settle down permanently in the countries they visited. Their main motive was to make sufficient money to buy gold and other consumer goods, and ultimately to build a house in Bawean when they returned.

The Baweanese started migrating to Singapore in the 19th century and this movement further intensified in the early 20th century due to the vast economic opportunities available here. Colonial records show that Baweanese migrants were a formal ethnic category of Singapore’s population in 1849, but given the active maritime movements criss-crossing Southeast Asia, it is highly likely that Baweans were already part of Singapore’s social milieu as early as the turn of the 19th century. These early settlers provided much-needed services in the port areas, town centres and even recreational arenas. At the time, Bawean men were known for their horse-handling and motoring skills and many worked as horse syces, drivers and water-boat workers. Even though many of these Baweanese saw themselves as sojourners, most of them settled permanently due to the higher wages they could earn here as well as the increasingly restrictive colonial policies that prevented them from easily returning to Bawean.

Ponthuk Living

The Baweanese community of Singapore grew out of successive waves of migrants settling permanently here from the mid-19th century onwards. Many Baweanese settled at the bank of the Rochor River between Jalan Besar and Syed Alwi Road. Pre-war shophouses located around Kampong Kapor Road near Jalan Besar were turned into ponthuks, such as Pondok Diponggo, Pondok Kalompang Gubuk and Pondok Gelam.

Courtesy of Hjh Junaidah bte Junit.

The ponthuk (Malay: pondok), a communal residence based on village affiliations back on Bawean, became an important social institution for the Baweanese community in Singapore until the end of the 20th century. These ponthuks, in effect shophouse residences set in urban locations around Singapore, initially served as temporary homes for the Baweanese newcomers and provided them with safety and other welfare services – a practice similar to the kongsi concept of Chinese clans. A newcomer lodged in the ponthuk until he had found employment and a permanent home usually provided by his employer.

As more Baweanese came to settle in Singapore and married locals or brought over their families, the ponthuk came to grow as a social institution that ensured the communal welfare of the Baweanese until they were financially able to set up their own home. It served not only as an institution that gave them a sense of socio-economic security but was also a micro-economic reflection of village relationships back on Bawean.

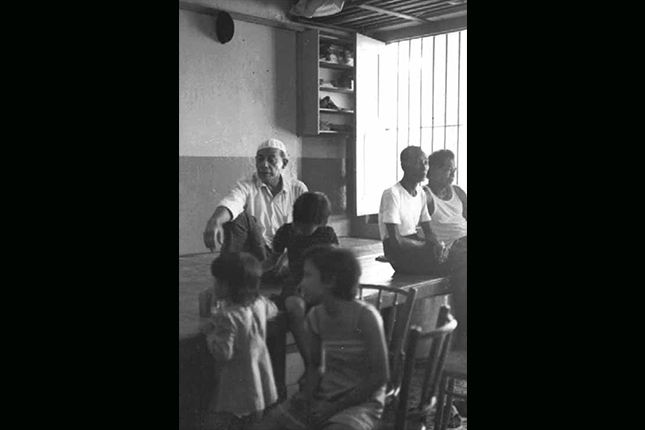

Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore.

One of the highlights of the Laaobe exhibition was the depiction of life in a ponthuk during the mid-19th to late 20th century and the vivid presentation of community-contributed artefacts. The ponthuk representation gave visitors an insight into the living conditions of the Baweanese settlers and the communal activities that contributed to the beginnings of a community group known for being close-knit.

A Pak Lurah or residence master would head each ponthuk and serve as the leader of that household. The Baweanese are known for making group decisions by consensus, and general assemblies and other meetings usually took place in the living room of a ponthuk. Generally, this area was restricted to male ponthuk residents and guests only. A typical living room in a ponthuk had a huge multi-purpose ambin (a low raised platform) and a communal dining table. The ambin, which usually covered one-third of the floor area, served several purposes – it could be used as a huge yet spartan bed for ponthuk bachelors, for daily solat (prayers) or even as a place where Qur’an recitations were performed.

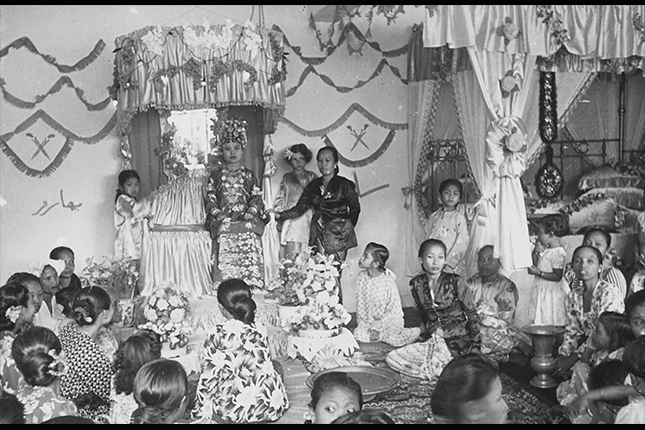

Courtesy of Hjh Junaidah Bte Junit.

Baweanese cultural norms and practices

Living in a close-knit ponthuk environment contributed to the formulation of cultural norms and practices within the Baweanese community in Singapore. These cultural norms, which are ill- practised today, include the concept of gotong-royong, or ‘mutual aid’. Gotong-royong is a shared cultural value across the different Malay communities and the spirit of ‘mutual aid’ was embodied in ponthuk life. Ponthuk residents were expected to assist one another in good and bad times, and contribute financially to the household. Weddings, thanks-giving customs, newborn baby celebrations and funerals were affairs that concerned the entire ponthuk community. Ponthuk living also contributed to the formation of social groups such as the kendarat (a voluntary service during wedding occasions), kompang (a handheld drum ensemble), berzanji (a religious recitation group) and kercengan, a quintessential traditional Baweanese group performance that blends Quranic verses and Baweanese chorale music.

Courtesy of the Hj Asmawi Bin Majid.

Persatuan Bawean Singapura (PBS)

Laaobe was produced in partnership with Persatuan Bawean Singapura (PBS - Singapore Baweanese Association), a social organisation formed in 1934 to assist and supervise all the ponthuks scattered all over the island at that time. Back then, PBS worked closely with the various ponthuks to help Singapore’s newly arrived Baweanese migrants by providing shelter and sustenance as well as aid to secure employment.

After 1962, ponthuks started closing down as families began to move out into single-family residences. Although the ponthuk has disappeared from Singapore’s urban landscape, PBS continues to play an important role in the context of Singapore’s multi-ethnic cultural milieu by promoting the language and culture of the Baweanese community. The group also organises charity and community events nationally that involve the larger multi-ethnic Singapore community.

Courtesy of the Baweanese Association of Singapore and the National Heritage Board of Singapore.

The Baweanese Community in Singapore today

The Baweanese today no longer live in ponthuks, but that has not diminished the community spirit of the people. The Baweanese word “laaobe” means “changed” and while transformation aptly describes the history of the Singapore Baweanese community over the decades, many aspects of Baweanese culture, heritage and values are still very much alive today.

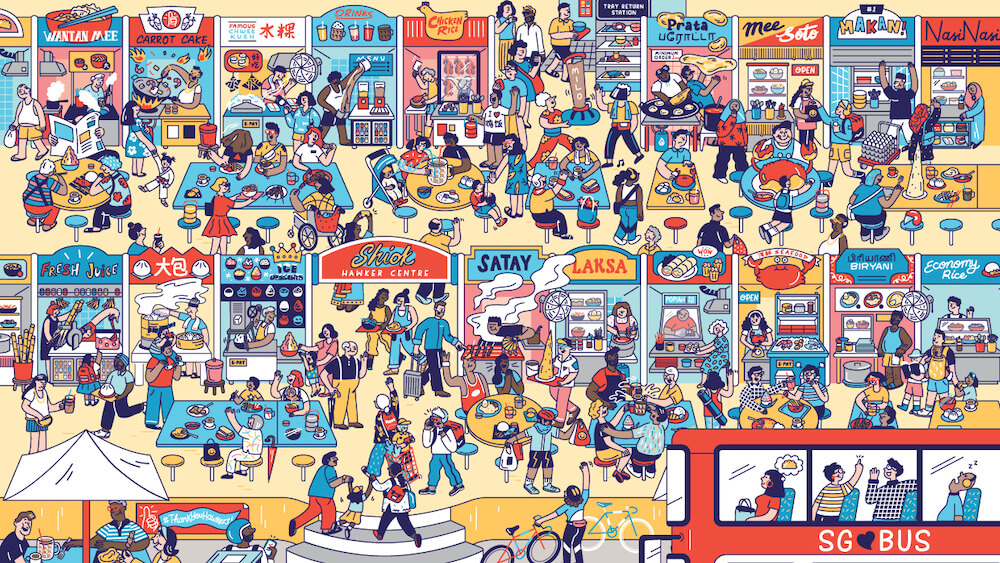

The many programmes supporting the exhibition were also opportunities for both Singaporean and foreign visitors to learn more about the Baweanese culture as well as its delicious cuisine, and about how the community has enriched the extraordinary cultural landscape that we enjoy in Singapore.

» Suhaili Osman is Curator, Malay Heritage Centre & Muhammad Qazim Abdul Karim is Assistant Manager (Outreach), Malay Heritage Centre