Building factories on a crocodile-infested swamp

Former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew surveying the swamp that was to become Jurong Industrial Estate. (27 October 1962. Image from the National Archives Singapore)

Former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew surveying the swamp that was to become Jurong Industrial Estate. (27 October 1962. Image from the National Archives Singapore)

A remote swamp with crocodile-infested waterways — the last place on anyone’s mind — transformed into a thriving industrial hub. Jurong, one of the most ambitious projects of modern Singapore, was materialised through foresight, determination and ingenuity.

Initiated by Dutch economist Albert Winsemius and Singapore’s minister of finance Goh Keng Swee, the plan to build Jurong Industrial Estate was born out of necessity as a result of Singapore’s high unemployment rate.3

As of 1959, an estimated 200,000 people, or 14% of the population were jobless. With the impending decline of entrepot trade and other economic factors at play, the issue of unemployment was expected to worsen as the population grew.4

Goh's Folly?

Sceptics scoffed at the pair’s plan — few could see rural Jurong’s potential. The project also seemed too costly. Reclamation, infrastructural work and the like would cost a staggering $100 million.5

And while there was a smattering of factories in Jurong, including one which produced canned kaya and curries, Singapore by and large had very little experience in manufacturing.6 In addition, observers felt that investors had little risk appetite to set up shop in Singapore following a spate of labour strikes.

Initial hiccups seemed to prove the sceptics right, as few investors took bait when the estate became ready for production in 1963 after 1.8 million cubic metres of earth had been moved.7 Critics thus named the endeavour "Goh's Folly".

Dr Goh persisted with the project anyway. He rolled out a few initiatives to lure investors. These included:

- the provision of generous tax incentives;

- ready-made factory spaces and infrastructure for companies to launch production;

- the promise of a stable labour climate via sound tripartite arrangements.

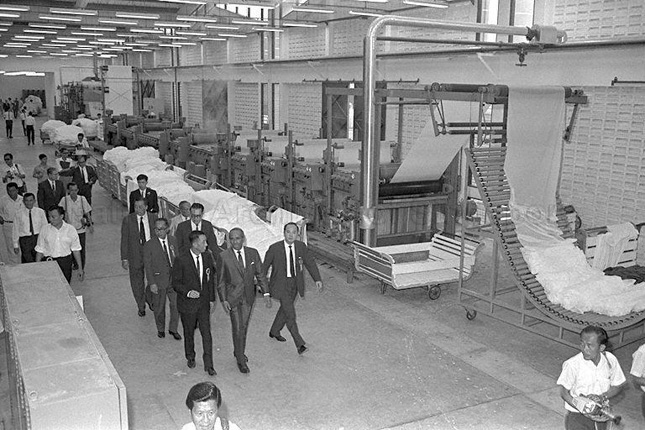

The Economic Development Board (EDB), established to helm Singapore’s industrialisation drive, courted producers of joss sticks, wigs, garments, fertiliser, plywood, acid and animal feed. Despite their best efforts, the team only managed to secure two investors: NatSteel and Pelican Textiles.

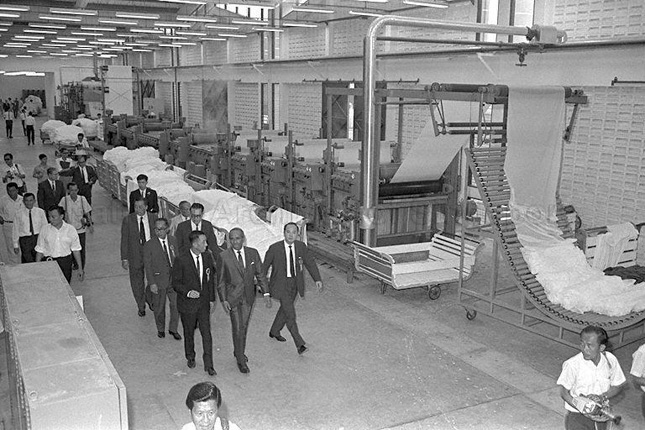

The Pelican Textiles Factory at Jurong Industrial estate in 1964. (Image from the Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore)

The Pelican Textiles Factory at Jurong Industrial estate in 1964. (Image from the Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore)

One factory-related event per day for 90 days

Then Minister of Fnance Goh Keng Swee speaking at the inaugural Jurong Town Corporation board meeting in 1968. (Image from the National Archives Singapore)

Then Minister of Fnance Goh Keng Swee speaking at the inaugural Jurong Town Corporation board meeting in 1968. (Image from the National Archives Singapore)

To give his fledgling project a much-needed boost, Goh instructed the EDB to conduct opening ceremonies daily over a three-month period. This was impossible considering that less than 10 factories were ready to start production.8

To populate the calendar, grab news headlines and build hype, the EDB team got creative. It held ceremonies when investors signed agreements to start work in the estate, for groundbreaking ceremonies, as well as official opening ceremonies.

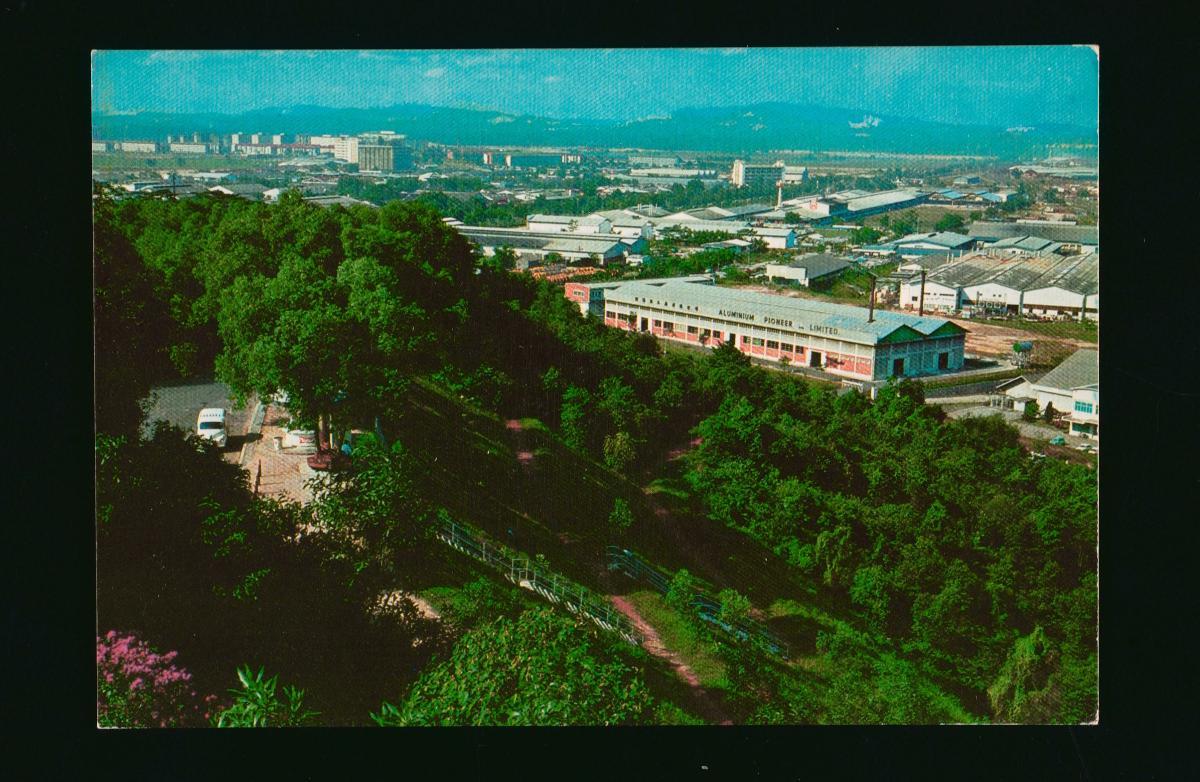

The Economic Development Board was tasked to launch events daily over a three-month period to declare to one and all that Jurong was open for business. (c. 1969. Image from the National Archives Singapore)

The Economic Development Board was tasked to launch events daily over a three-month period to declare to one and all that Jurong was open for business. (c. 1969. Image from the National Archives Singapore)

The tactic bore fruit, and by the end of the 1960s, 181 factories were in production. The project's success set the stage for subsequent chapters of industrial development in Jurong, with new investors in a wider variety of sectors streaming in steadily.9 Goh's "Folly" had become the nation's glory.

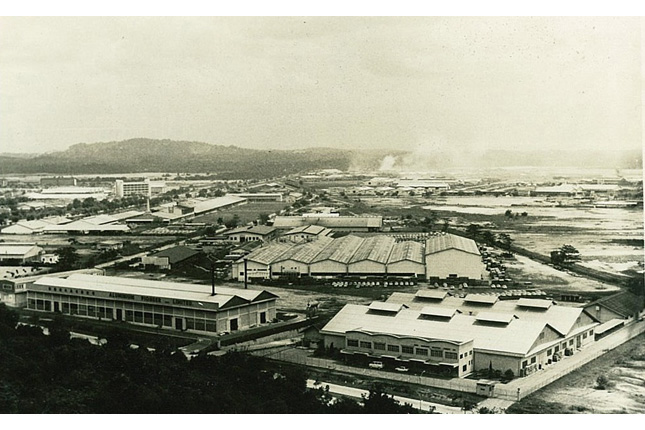

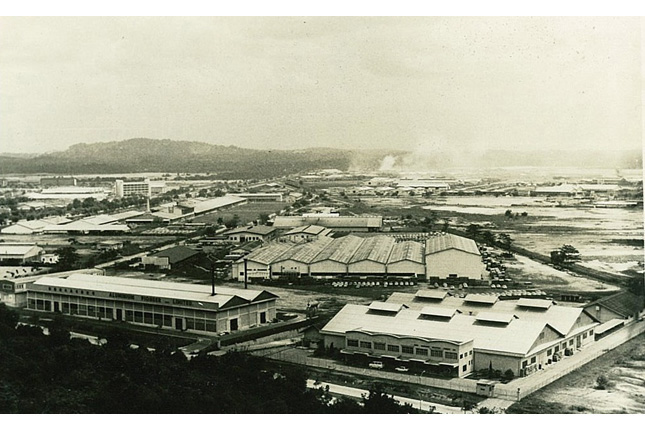

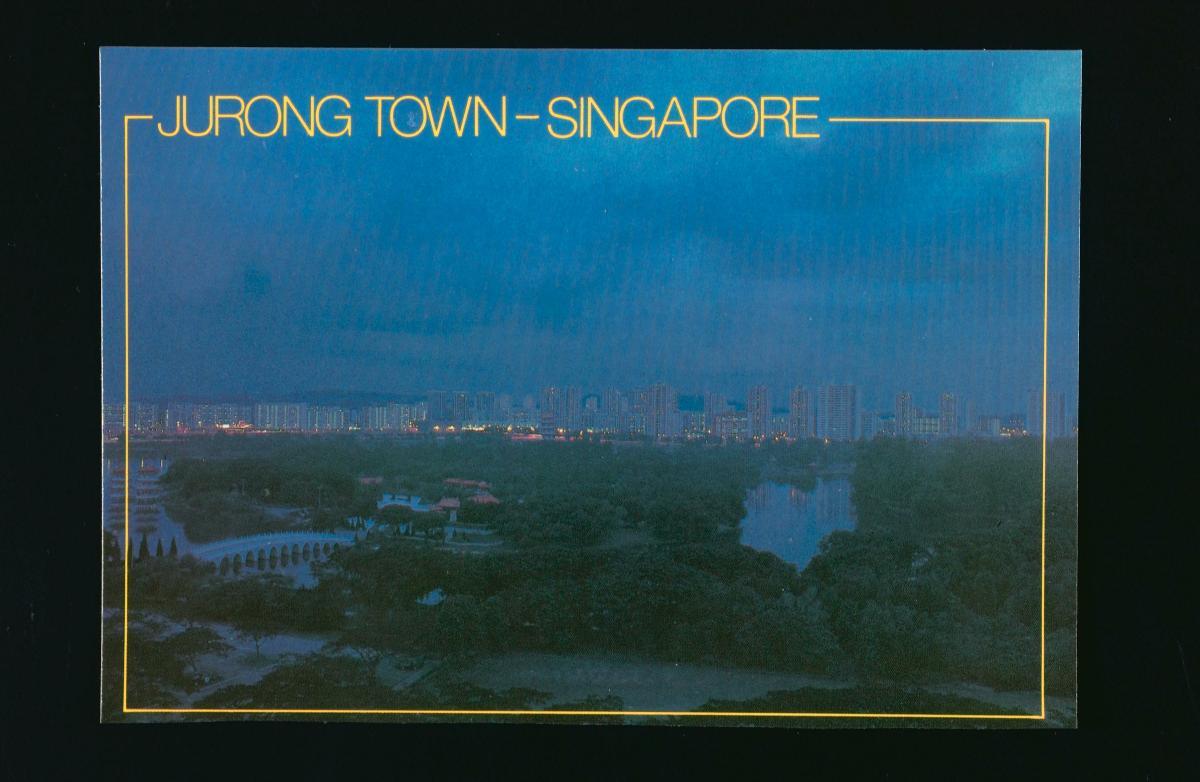

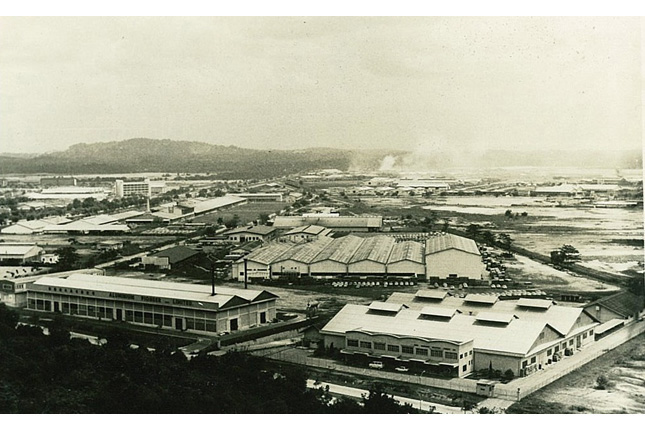

By 1969, Jurong Industrial Estate was home to 181 factories and a 20,000-strong workforce. (c.1960s)

By 1969, Jurong Industrial Estate was home to 181 factories and a 20,000-strong workforce. (c.1960s)

Few takers for life in the “wild, wild west”

The path to success was bumpy to say the least, with accounts of Jurong in the early 1960s describing the roads as "full of pot-holes, some deep enough to swallow a wheel".10 It was a desolate area, "hot and dusty" with no trees or grass, and it was filled with mosquitoes. Workers also bemoaned the lack of recreational activities, save for leisurely walks to Jurong Lake.

To encourage the working community of Jurong to live where they worked, open-air cinemas were constructed while boats, which workers got to use for free on Sundays, were added to the lake.

Dr Goh also “cornered” companies into offering staff a housing allowance to incentivise them to move to Jurong. He would build a tollgate otherwise, he said, where buses and lorries ferrying workers would be charged $50 a month.

These measures were effective. Work on Jurong New Town began in the 1960s11 and by 1969, 16,000 people were living in flats and shophouses built by the Housing Development Board (HDB). The Jurong Town Corporation (JTC), a specialised agency formed to develop and manage industrial estates, took over residential and industrial development for a period before the HDB returned in 1982 to handle and oversee the area’s housing needs.

Low-cost flats were erected to attract people to live and work in Jurong. (c.1964. Image from Jurong Town Corporation)

Low-cost flats were erected to attract people to live and work in Jurong. (c.1964. Image from Jurong Town Corporation)

The JTC was behind landmarks such as the diamond blocks of Taman Jurong at Yung Kuang Road where companies rented flats to house staff. The four blocks, completed by JTC in 1973, form a unique diamond footprint and have inner facing common corridors to foster a sense of community.12

Gradually, bus services, wet markets, food centres, clinics, community centres, retail areas, sport facilities, as well as public parks and gardens were added to the mix.

Other landmarks which rose in Jurong include Jurong Town Hall. Perched on a little hill, it served as JTC’s headquarters from 1974 to 2000.13 Now a national monument, the geometrically outstanding building is emblematic of Singapore’s successful industrialisation programme.

Jurong Town Hall, a landmark representing Singapore’s confidence in its industrialisation ambitions. It served as the Jurong Town Corporation’s headquarters for about a quarter of a century.14

Jurong Town Hall, a landmark representing Singapore’s confidence in its industrialisation ambitions. It served as the Jurong Town Corporation’s headquarters for about a quarter of a century.14

By 1980, more than 110,000 people lived in JTC housing units in Taman Jurong, Boon Lay Gardens, Teban Gardens and Pandan Gardens.

The addition of the Chinese Garden at Boon Lay Way added even more life and vibrancy to the district. Designed by Taiwanese architect Yu Yuen-Chen, and built between 1971 and 1975, it comprises bridges, pavilions and a pagoda inspired by classical northern Chinese imperial architecture. It was a popular spot for wedding photography during the 1970s and 1980s.

The Singapore Chinese Garden was commissioned to bolster Jurong’s offerings. (c.1980s. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

The Singapore Chinese Garden was commissioned to bolster Jurong’s offerings. (c.1980s. Image from the National Museum of Singapore)

The Jurong of the future

Jurong’s industrial activities are anchored by clusters such as CapitaLand’s International Business Park and JTC’s Jurong Innovation District which host a diverse and flourishing ecosystem of international and local corporations.15

To spur the country’s next phase of economic transformation, a 360-hectare site in Jurong has been earmarked as Singapore’s next “Central Business District” for sectors such as maritime, energy and IT. Announced in 2017, the Jurong Lake District project will be developed over the next few decades and is expected to generate more than 100,000 jobs.16

The Jurong Lake District is also set to welcome a mini Marina Bay Sands arena which is slated to house hotels, attractions, eateries and shops.

A view of Jurong today. (c. 2015. Image from https://ghettosingapore.com/)

A view of Jurong today. (c. 2015. Image from https://ghettosingapore.com/)