TL;DR

Commemorating the 75th anniversary of the Fall of Singapore, photographer Nicky Loh meets four survivors who have lived through the trying times of the war, and captures vignettes of their stories.

Written and photographed by Nicky Loh

I was commissioned by the National Heritage Board to create a photo essay of World War II (WWII) survivors to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Fall of Singapore.

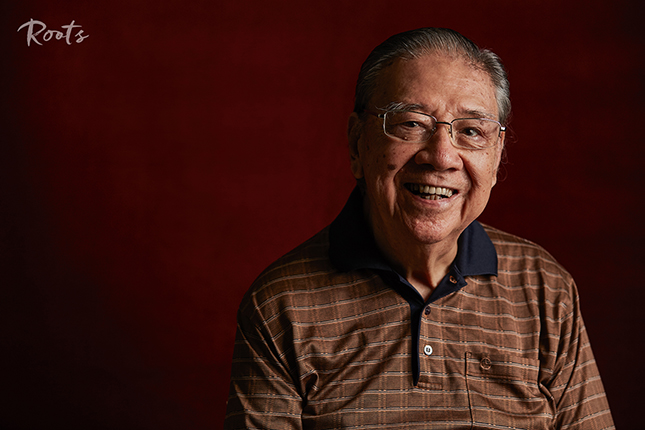

My pitch to them was to shine a light on the wrinkled faces of these amazing people through tight portraits on a red background. The red was meant to symbolise self-sacrifice and also serve as a metaphor for Singapore. I wanted pensive, stark and strong portraits to do the talking. My pre-conceived narrative had a more sombre tone, where the survivors reflected on their experiences during the war. It was not until I met the first subject for the photo shoot, did I realise that my direction was totally wrong.

When you find yourself in a situation way beyond your control, all you can do is to follow the instinct to survive. Perhaps after a horrible ordeal, do you then realise how precious life is, and you try to live the rest of your life in the most fruitful and meaningful way.

When we arrived for the photoshoot and video interview with Mr Joseph Conceicao, 92, a former Singapore ambassador and Member of Parliament, at his apartment in Marine Parade, he sternly asked one of the crew, "Tell me young man, why is your hair golden?" Everyone froze awkwardly for about two seconds before Mr Conceicao broke into a hearty laugh and said, “It’s okay young man. It looks good!” Age was evident, but the fire in his heart was still burning bright.

We were then invited into his apartment, which had a hearty collection of antiques and photographs collected from around the world, all displayed and labelled meticulously on his glass shelves. Without a doubt, he had travelled extensively throughout his life after the war.

"Call me Joe, young man," he said to me.

Mr Conceicao was a young man of around 17 years old in 1941 when the Japanese started bombing Singapore. His memory was still as sharp as ever as he recounted an incident with his cousin after the Japanese heavily bombed the Orchard and Newton areas to cut off communications:

"My cousin and I were curious and wanted to see the aftermath, so we walked across a field near our house towards a junction in the Newton Circus area. Suddenly I heard him gasping and I turned around to see what had happened. We saw hands, heads maybe, legs, and parts of the human body lying about. That affected him throughout the course of the war and his life."

When Mr Conceicao's family eventually concluded that their home was too dangerous to continue living in due to the proximity of the bombings, they relocated to the basement of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank (HSBC) building on Battery Road.

"While walking there with our belongings, we saw British soldiers who were taking off their military uniforms. Fleeing. To our shock, when we arrived at the Hong Kong Bank, there were more British soldiers sprawled across the place when they should be out there fighting. This gave us a terrible impression of them. Sir Shenton Thomas (then Governor of Singapore) said that Singapore must not fall, it shall not fall, but the next day it fell."

Singapore fell on February 15, 1942.

Ms Mary Magdeline Pereira, 75, was born that year inside the Tiong Bahru air raid shelter – tragically one day after her father was called for duty and perished.

"My father was activated for duty on January 21, 1942, and he told my mother, "I don't know if I'll return." True to his words, that was the day that Singapore had the worst casualty from the Japanese bombing. Many people died. I heard my father was carrying the injured when shrapnel hit him on his chest and on his face. That was how the war began for me - with the loss of my father just a day before I was born.

That very night, an air raid occurred and her family had to seek refuge inside the shelter located at Block 78, Guan Chuan Street. Inside, Ms Pereira's mother went into labour under the care of Professor J. S. English, Singapore's first professor of obstetrics and gynaecology, who was in charge of the medical unit in the shelter. With help from him and his wife, Mrs Pereira delivered her daughter just after midnight on January 22, 1942.

As I photographed her at the entrance of the very shelter she was born in, she told me, "I think the war was a period where I grew up carefree and wild. I had so much independence and that is what gives me so much resilience to overcome all odds. I went through quite a tough time but I viewed it as an obstacle to overcome. When I could not get my teaching post in Singapore, I went to the United Kingdom to be a barrister at the age of 55. So don't tell me there isn't a time to learn.

"WWII has brought out one class of people, a generation that has resilience and has been able to overcome all odds. That was actually the good part of the war," added Ms Pereira.

It is a cold hard fact to confront but within the next two decades, there will be very few survivors of the Japanese Occupation around to tell the incredible personal stories that can seem straight out of a movie.

My first impression of Mrs Helen Joseph, 88, was that she is a very sweet lady who constantly has a smile on her face. Her demeanour reminded me of Betty White of the 1980s American sitcom, Golden Girls. Her home has a grand clock that rings a soothing chime every 15 minutes - a chime that sticks with me even till today. I thought, "How could someone as nice as her go through something as terrible as the war?"

Mrs Joseph was just around 12 when the Japanese Occupation began.

"They took Chinese people by the lorries including my neighbour's husband," Mrs Joseph recalled. "We then heard rumours that the Japanese had dug a hole in the Padang, laid out the Chinese men and shot them with machine guns. One by one, the men fell into the hole. One pretended that he was dead and waited till it was all quiet and then he ran away to tell everybody of the massacre. My neighbour never saw her husband again."

It was known that the Japanese military committed numerous atrocities against civilians, especially the Chinese. During the Japanese Occupation, they introduced the system of "Sook Ching", which means "purge through purification" to get rid of civilians deemed to be anti-Japanese. The massacre is believed to have claimed the lives of around 20,000 ethnic Chinese in Singapore.

Mrs Joseph stayed with her uncle and relatives in Government Quarters along Rowell Road in Little India. Yet even during times of hardship, Mrs Joseph remembers the true communal spirit with many of her neighbours.

"It didn't matter if you were Chinese, Indian, Malay or Eurasian like me, everyone helped one another because we needed to. We had to queue up for food rations at 3am in the morning. Even so, when it came to our turn, the food would have run out and the person in charge would tell us to go away. Thankfully neighbours who had queued earlier would also share what they had with us."

Feisty and seemingly fearless, Mrs Joseph also harboured secrets of the Japanese Occupation.

"The [prisoner of war] camps were near our place and we could see inside. The British soldiers were so skinny, all ribs. My sister and I would secretly pack some bread given by the Japanese into a bundle and leave them near the barbed wire fences and shout "Johnny, Johnny!" The next day the bundles would be gone."

"Who is Johnny?" I asked.

"We didn't know their names so we called them all Johnny!" laughed Mrs Joseph.

I arrived earlier than the rest of the crew at Mr William Gwee's place in Lothian Terrace near Siglap and saw him reversing his car into the front porch of his house. Yes! At the age of 82, Mr Gwee is still actively driving, though he murmured to me that young drivers nowadays are reckless. The gate of the house has a beautiful flower structure that grows above it, making it look like a Tim Burton film set.

Students and researchers of Peranakan and Straits Chinese studies will no doubt be familiar with Mr Gwee, a fifth-generation Singapore Baba. Mr Gwee and his son, Andy, are prolific collectors and this was evident as soon as I stepped into the house. Mr Gwee probably has the largest collection of Baba Malay books in the world, and also collects memorabilia and artifacts pertaining to WWII, medicine and porcelain.

Mr Gwee showed me into his study, which was indeed a treasure trove of the past, including hundreds of folders of newspaper cuttings, documents and letters, all purposefully organised by themes and topics.

When war reached Southeast Asia, Mr Gwee, then eight years old, was about to start Primary 2 at his school.

"I must say that the experiences I went through growing up during the three and a half years of the Japanese Occupation helped provide me with an accelerated maturity."

The day Singapore became Syonan-To, the name given to the island by the Japanese during the Occupation, is still vivid to Mr Gwee.

"During the bombing days, before the surrender, my family took shelter at 97 Devonshire Road at my grand-aunt’s house where we could see the Cathay Cinema. It was the tallest high-rise building in Singapore back then. Every day I saw the Union Jack of the British flag, fluttering high up on a pole on top of the building."

"On that day, during the fall of Singapore, I was probably the first to realise that Singapore was about to change because when I looked out of the window at the building, I saw a different flag. It was a white flag with a red circle in the centre. So I shouted excitedly to the rest about the strange-looking flag above Cathay Cinema and my father came out and exclaimed, "Sudah habis!" The two words literally translate to,"We are finished."

Three or four days after the surrender, the Japanese chased Mr Gwee and his family out of the house and they took shelter near his father's friend's home near the Sultan Mosque after much wandering around. "When we walked on the streets we found out that thousands of people were also on the streets without a home. All of them were carrying bundles of food, clothing, bags and suitcases as if they were travelling. I was given small bundles to carry but after a long walk the bundles became quite heavy."

After a long refuge at Mr Gwee's father's friend's house after the fall of Singapore, the streets were watched by Japanese soldiers.

"We wanted to return home but there was a Japanese sentry post on the road who arrested all the men that went past. Against the advice of his good friend, my father brought us to a table at the post and shouted some Japanese words and showed some pictures of him and his former bosses." Mr Gwee's father had been under the employment of a Japanese company before the war started.

"This aroused the curiosity of the Japanese officers and soldiers, which I supposed save our lives because after that, the Japanese soldiers stamped something on each of our arms and shouted at us to move on."

As Mr Gwee and his family walked home to Devonshire Road, he noticed that there were only women on the road, and he wondered why his father - a man - was allowed to roam the streets with his family unscathed. Many women they encountered along the way asked Mr Gwee's father what had happened to their loved ones. He could not answer. It was only after the war did everybody learn that most of the young men in Singapore were massacred and never came back.

Mr Gwee reminisced, "75 years later, whenever I meet people who have been through the war, I ask them whether they had lost anybody during that period now known as 'Sook Ching'. I have not come across anybody who said no. Every one of them had lost somebody."

"After Japan surrendered, the actual handing over of Singapore from the Japanese to the British took place in mid-September 1945. It was a big affair for the Singaporeans because of the sufferings they had to endure for three and a half years. It was time to see an end to their ordeal. So they came in the thousands and waited at the Padang opposite the City Hall building. When the Japanese came to surrender and marched up the steps of City Hall led by General Seishiro Itagaki, the people booed at the Japanese knowing that this time they could get away with it," added Mr Gwee.

"It was not until a few days later that Singaporeans had another interesting sight. They (the British) made the Japanese soldiers dig up the ground in front of City Hall to fill up other holes in front of the building. A huge crowd was watching the Japanese having to work for us for the first time. You saw nothing but smiling faces. Excitement. Sparkles in their eyes. Knowing that the worst was over."

Perhaps everything does happen for a reason. These were ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances - caught in a dreadful war that led to the eventual independence of Singapore, a home to many of us now. Fate must have played a part, but let us not forget that our nation was also built upon a generation of people who endured a time we cannot imagine today. We therefore honour them by remembering their stories.

Watch the series: