Read more about PSM’s efforts to safeguard Singapore’s built heritage in MUSE SG Vol 14, Issue 1.

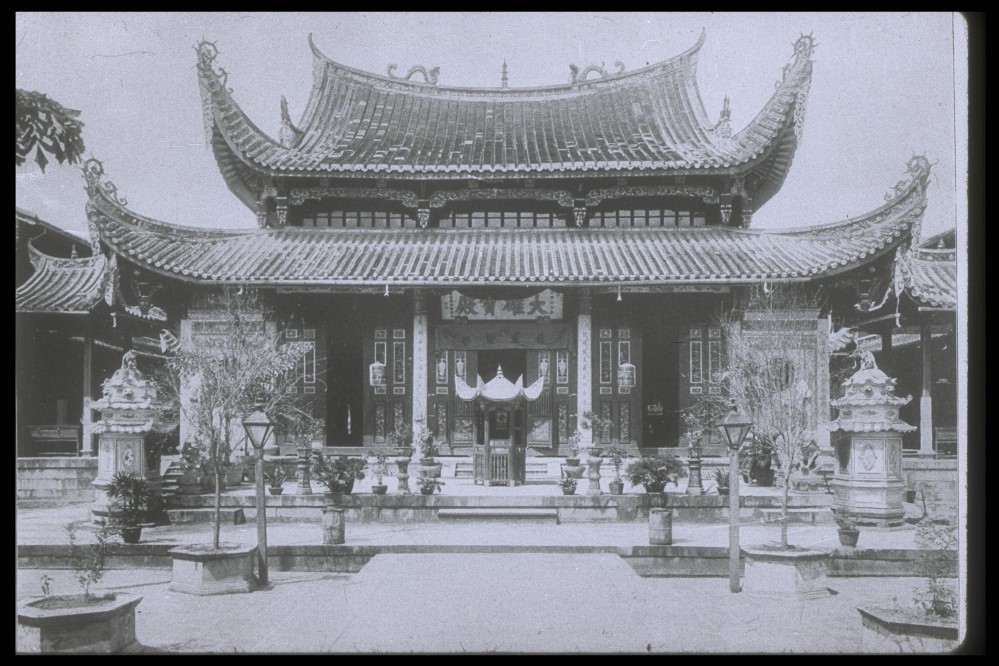

Built: 1902–08

Restored: 1991–2001

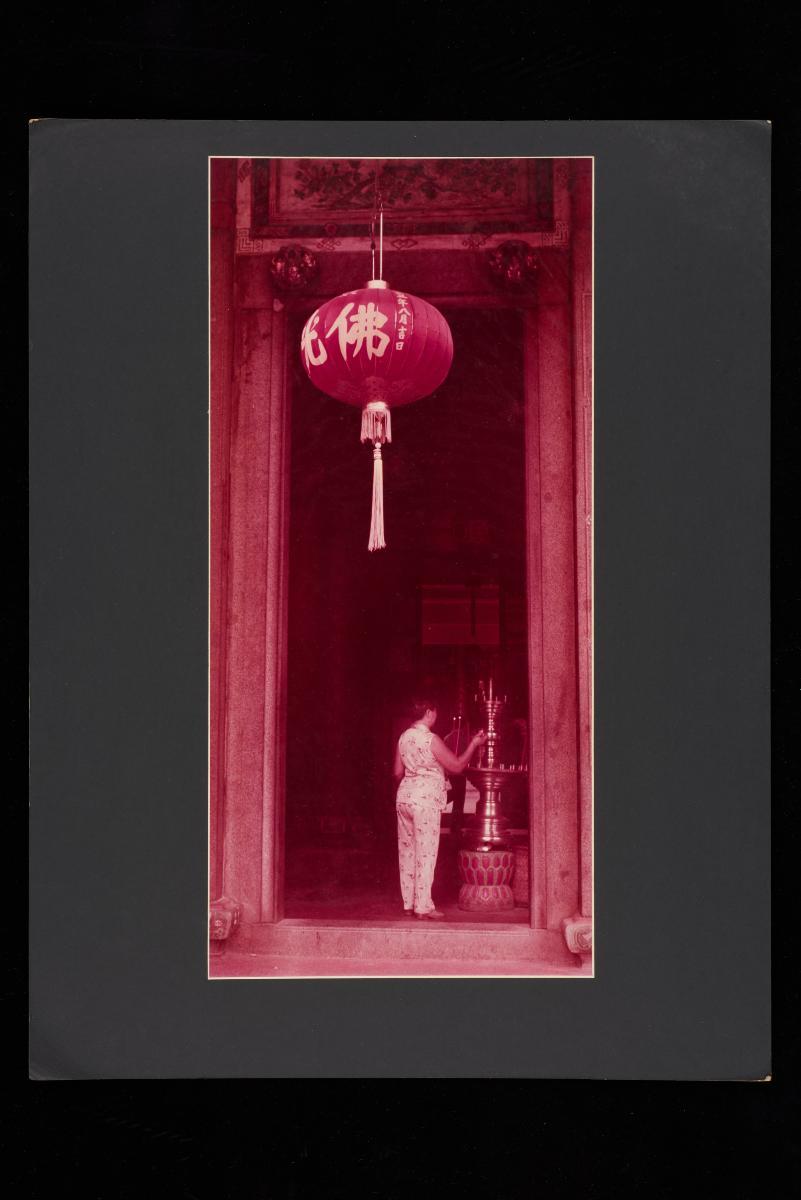

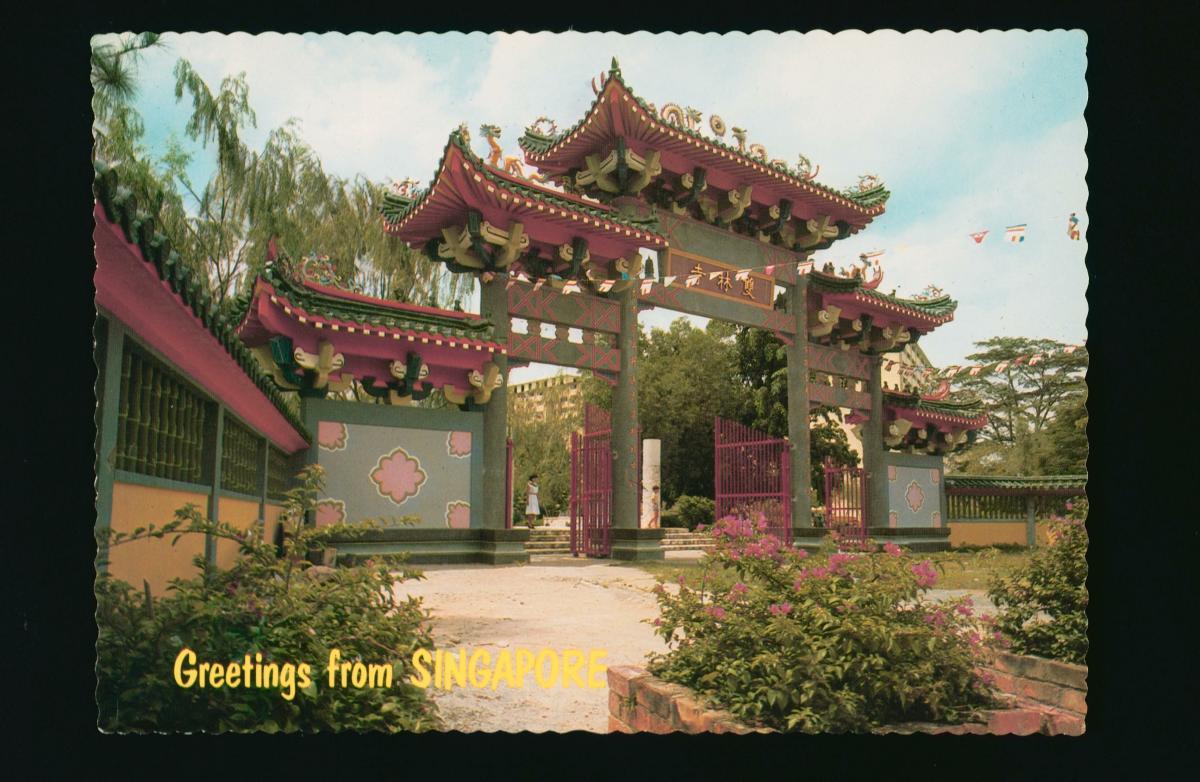

Built in the early 1900s, the Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery (former Siong Lim Temple) houses one of the oldest Buddhist temples in Singapore. It was built on land donated by influential businessman and devout Buddhist Low Kim Pong; today, the monastery is nestled amidst high-rise public housing flats in Toa Payoh.

There are three main buildings in the monastery. The main prayer hall, known as the Mahavira Hall (or Daxiong Baodian), was constructed in 1904, while the entrance hall, called the Tian Wang Dian, was built the following year. These two structures were gazetted collectively as a national monument. In 1903, the Dharma Hall was completed; however, this was rebuilt in the 1970s due to structural deterioration. Decades later, the Dharma Hall was again rebuilt according to its original architectural style from 1903, and this new structure was completed in 2016.

Modelled after the historic Xichan Temple in Fuzhou, China, the monastery follows the traditional conglin layout in which the various structures are symmetrical in plan, separated by courtyards and usually face the north-south direction with the entrance facing the south, according to fengshui principles. The conglin layout is meant to instil monastic discipline.

The overall architecture adopts a traditional Hokkien style, with a blend of Fuzhou, Quanzhou and Zhangzhou characteristics apparent across the various structures in the complex. For instance, the sharply curved corners on the roof are typical of the Fuzhou style, while the other buildings have bigger, heavier roofs with corners that curve at a gentler angle, which are distinctive Quanzhou features. These two architectural styles are seen in the double-tier roof of the Mahavira Hall: the upper-tier is of the Fuzhou idiom, while the lower-tier is Quanzhou style. The Zhangzhou style can be glimpsed in the roof of the Tian Wang Dian. It is very similar to its Quanzhou counterpart; the only difference is that the roof of the former has a steeper slope and a more complex roof truss.

From the 1990s up to the 2000s, the monastery carried out a series of restoration works to repair much of its structures which had fallen into disrepair. Significantly, the Bell and Drum Towers, which had been rebuilt in the 1970s, suffered from spalling concrete and had to be demolished and reconstructed. The temple committee consulted traditional architecture experts, and extensive research was conducted to recreate the towers, using photographs from the 1900s as a reference.

Modern technology and materials were employed to ensure that the finer architectural details specific to the Fuzhou style, such as the elegant upswing of the roof eaves, would be rendered in a way that could withstand the test of time. Wall motifs that had originally been made of clay and mortar were recreated on granite for a longer lifespan. For the same reason, Chengal timber, which is more termite-resistant, was chosen instead of the original Chinese fir.

In the mid-2000s, the monastery experienced water leakage in its roof. The roof tiles had been laid 20 years ago using the traditional wet-lay method whereby a mortar bed held the tiles on the pitched roof. However, this method was not appropriate for Singapore’s tropical climate—hairline cracks formed on the mortar and roof tiles over time, leading to water leakage. In planning for the reconstruction of the Dharma Hall in 2008, the monastery consulted their Buddhist architectural adviser from Hong Kong, the Venerable Wang Fun, who advised adopting the dry-lay method for the roof tile installation, while a Japanese roof tile manufacturer was also roped in to provide details on the installation.

Eventually, the supporting frame for the tiles was secured on the timber frame underneath with fasteners, and all timber structures beneath were protected by a water-tight roof. The dry-lay method was employed to replace the roof tiles for the Dharma Hall, spanning some 7,000 m2, and it has proven to achieve a very high degree of watertightness.

After more than two decades of restoration to its weathered structures, the Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery today proudly presents a fresh face to visitors from all over the world.

About The Preservation of Sites and Monuments

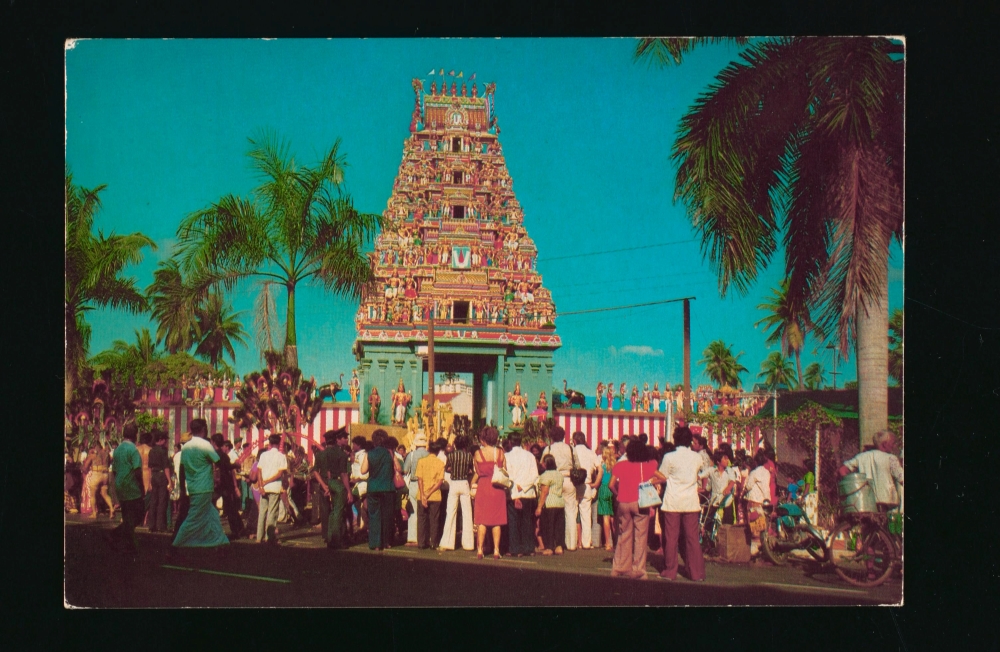

The Preservation of Sites and Monuments (PSM) is a division under the National Heritage Board. Its primary role is to safeguard Singapore’s built heritage by identifying monuments that are of “historic, cultural, traditional, archaeological, architectural, artistic or symbolic significance and national importance”, and recommending them to the state for preservation. Gazetted National Monuments are accorded the highest level of protection by law. National Monuments comprise religious, civic and community structures, each representing a unique slice of history in multicultural Singapore. Read more about Preservation of Sites & Monuments, and National Monuments here.