Gwee Thian Lye made his stage debut in 1984 while in his mid-40s, performing in Pileh Menantu (Choosing a Daughter-In-Law). It was the first step in an illustrious career that would see his stage name of G. T. Lye become synonymous with the arts of wayang peranakan and dondang sayang.

Watch: Stewards of Intangible Cultural Heritage Award - GT Lye

At the time of his debut, Pileh Menantu was the first wayang peranakan play to be staged in Singapore in 25 years. Inspired by the popular Malay-language theatre of bangsawan, the Peranakan community had devised wayang peranakan, which is performed in Baba Malay. This theatrical form captured the imagination of the Peranakans in the early 20th century and had a comeback in the 1950s after World War II, before gradually fading from the limelight by the 1980s. In this sense, Pileh Menantu marked a watershed in the revival of a regional art form with deep, cross-cultural roots, and through which the Peranakan community in Singapore continues to showcase its heritage, as well as sustain its culture for future generations.

Gwee also specialises in dondang sayang, the improvisational, bantering performance of pantun (quatrains in Malay or Baba Malay), which is an important art form beloved by both the Malay and Peranakan communities.

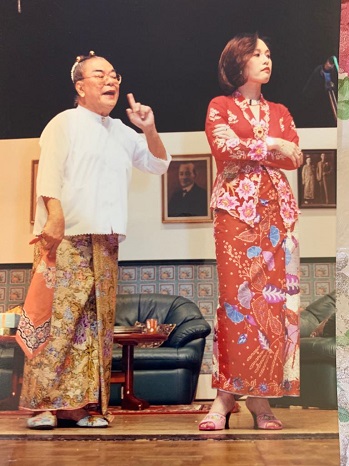

For Gwee, Pileh Menantu was the start of a four-decade stage career as an actor, scriptwriter, director and dialogue coach for both wayang peranakan and dondang sayang. Answering a newspaper advertisement, Gwee auditioned and won a role in Pileh Menantu. Gwee then appeared as a nyonya matriarch on stage for the first time the following year, in 1985’s Buang Keroh Pungot Jernih (Let Bygones be Bygones).

The play’s producers, the Gunong Sayang Association (GSA), had been unable to find a suitable female actress to fill the role of the matriarch, leading Gwee to propose himself. Male actors playing female wayang peranakan roles had long been a tradition in the community, and Gwee’s own father Peng Kwee had been a renowned pantun composer, dondang sayang singer and female impersonator in wayang peranakan from the early 20th century. By the 1980s however, wayang peranakan had not been performed in Singapore since the early 1960s, such that many people doubted that there were any male actors left who would be able to perform convincingly as matriarchs.

In every detail, a facet of heritage

Gwee’s attention to detail proved invaluable for his performances. He silenced the naysayers with his recreation of the coiffure (such as the sanggul, a tightly coiled hair bun), costume (such as the baju panjang or long dress) and jewellery, as well as the precise, at times cutting speech and mannerisms of these bibiks. At the Victoria Theatre in March 1985, and for all his subsequent roles in the following decades, Gwee demonstrated his capacity to “transform to the fullest”, under his chosen stage name of G. T. Lye.

Most wayang peranakan plays feature domestic settings and everyday environments, and reflects Peranakan social and cultural values. To fulfil his matriarch roles, Gwee drew on his personal memories and observations of “the rich, the poor, the good, the bad, the ugly, the scandalous” personalities that had passed through his childhood home. “(From) the age of 11, I have always opened my eyes and ears to the beautiful hairdos, the crispy (sic) baju panjang, the beautiful kasut manek (beaded slippers)”, he recalled.

The complex social interactions and hierarchical signifiers between women in the Peranakan community were absorbed by Gwee as well. “(The matriarchs) are very fastidious (in) the way they speak, the way they deliver the language and who they are speaking to. It differs from one matriarch to another”, said Gwee.

Gwee’s meticulous study of an earlier generation of nyonya matriarchs or bibiks yielded invaluable insights into an already vanishing way of life. As he observed: “I have experienced life with these kinds of people… I am delivering something that you cannot see (regardless of) how (much) money you pay... it’s all in the past, the genuine characters which nowadays, because of modernisation, you won’t be able to see ever again.”

Moreover, the art forms of wayang peranakan and Peranakan dondang sayang are traditionally performed in Baba Malay, and a high level of fluency and a quick wit is required in order to engage in the light-hearted verbal sparring or repartee which it entails. With Baba Malay incorporating Malay, Hokkien and other Chinese dialects, these art forms have helped build bridges of deeper understanding between communities. As Gwee says: "For centuries, the Malay and the Peranakan communities have been able to communicate with each other in a beautiful and harmonious way – not just through daily conversations but also through our music, poems and literary texts.”

A living legacy

In the late 1980s, Gwee performed regularly with a professional wayang troupe in Melaka, further honing his craft and depth of cultural knowledge. Over the next four decades, he participated in 23 wayang peranakan productions throughout the region in various capacities, including scriptwriting (such as in 2000’s Chuy It Chap Goh, the first script penned by Gwee) or as a language consultant.

Gwee also became a familiar face on Malay television and in dondang sayang acts, including appearing alongside stage veterans Momo Latiff and Hyrul Anwar in 2010’s Kelab Dondang Sayang, as part of the Esplanade’s Pesta Raya Malay Festival of Arts. He has also performed dondang sayang in a number of Peranakan wedding performances around the world, working in collaboration with STB to promote Peranakan culture in cities like Paris, Chengdu and Seoul. Gwee also continues to sustain wayang peranakan by mentoring young performers, such as skit performers from the Chitty Melaka association, and sharing knowledge with researchers.

Through these efforts, Gwee’s deep cultural knowledge has been passed on to a new generation through his assiduous mentorship. Ivan Heng, founder and artistic director of theatre company Wild Rice expressed appreciation for Gwee’s commitment to nurturing future generations of artists and audiences through his interviews, workshops and rehearsals. Similarly, Alvin Teo, president of the Gunung Sayang Association, has credited Gwee’s in-depth knowledge of Peranakan culture and practices as integral to recreating wayang peranakan.

John Teo, former General Manager of the Peranakan Museum and current Deputy Director of Research at the National Heritage Board, summed up Gwee’s accomplishments: “Unlike Peranakans of (the post-independence) generation, who are now trying to rediscover aspects of our heritage, he has lived the culture. His mentorship and guidance have been invaluable assets to the museum and its curators. In our collective efforts to preserve Singapore’s intangible cultural heritage, G. T. is one of last remaining authorities, an irreplaceable expository agent of the customs, traditions and practices of a bygone era.”