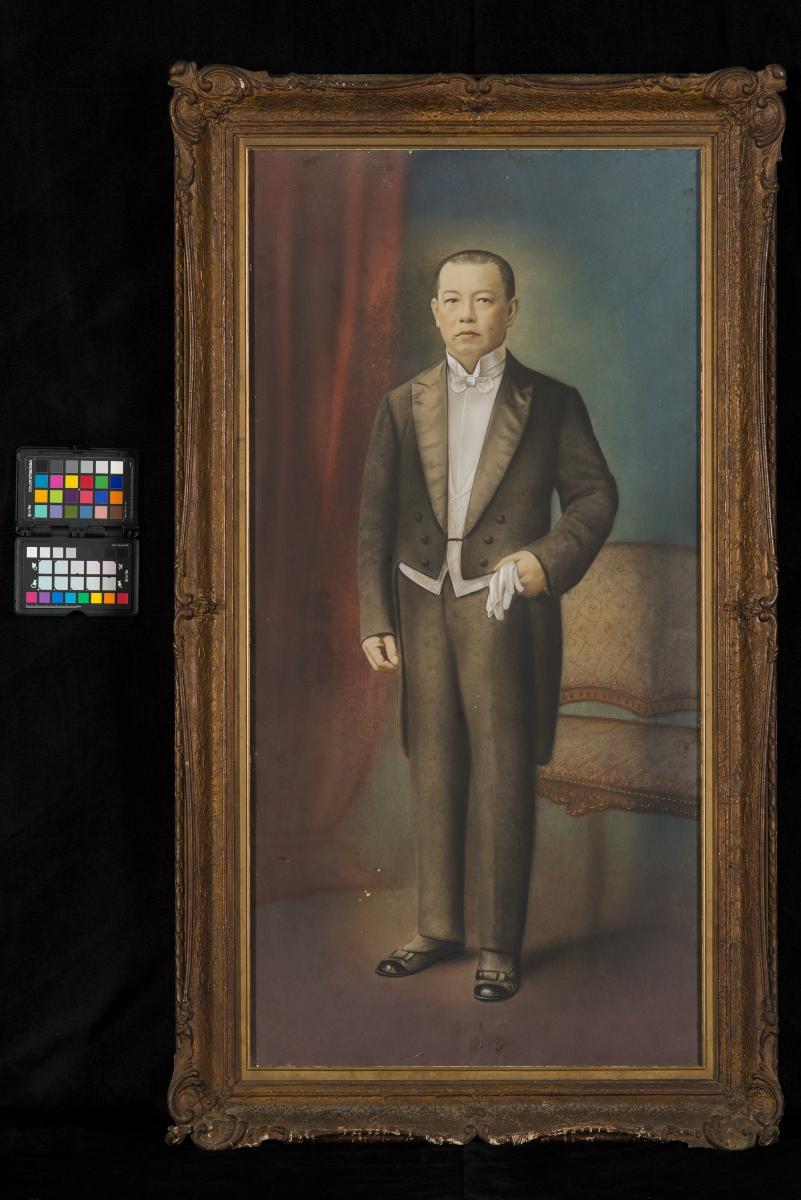

Long considered ritual objects rather than works of art, ancestral portraits were produced in large numbers throughout China for ritual veneration since the 18th century. They were commissioned by relatives of the deceased, and usually hung only during the death anniversary of the departed and during annual festivals such as the Chinese New Year or the Autumn Sacrifice for All Souls. Many of these portraits were painted posthumously by anonymous artisans in workshops, sometimes many years after the death of the individuals represented. For these reasons, Chinese connoisseurs of literati painting as well as Western art historians and museums have until very recently been unenthusiastic about these paintings. Stuart notes, “artists operated within culturally determined conventions and blended realism and idealization in mixed degrees, depending upon the intended function and audience for a portrait”.Although these four Zhou ancestral portraits do not represent imperial courtiers or royalty, they are of interest to the ACM because they represent the phenomena of transnational history and reverse migration: of diaspora Chinese who had emigrated to California, earned their fortune there, and then returned to China to become powerful and influential major landowners in the Chang village in Kaiping, Guangdong. (Kaiping has traditionally been a region of major emigration particularly from the mid-19th to early 20th century) They can also be used to illustrate important concepts such as filial piety, or dress and rituals.Provenance: Collection of Mr Chau Tak VuiAs these portraits were personally retrieved from the ancestral shrine (jia miao家廟) in the main hall (da ting 大廳) of his ancestral home in Kaiping, Guangdong, China by Mr Chau (the 24th generation) more than two decades ago, they have not been altered or remounted for sale to Westerners. They are also interesting because they feature two generations (the 16th and 18th generation) of ancestors, and thus allow a study of a family ‘archive’, documenting the creation of (and evolution in representation of) family ancestral portraits in sets.General ReferencesJan Stuart and Evelyn S. Rawski, Worshiping the Ancestors: Chinese Commemorative Portraits, 2001Richard Vinograd, Boundaries of the Self: Chinese Portraits 1600 – 1900, 1992Ladislav Kesner Jr., ‘Memory, Likeness and Identity in Chinese Ancestor Portraits’, Bulletin of the National Gallery in Prague III:IV: 1993-1994.Joan Hornby, ‘Chinese Ancestral Portraits: Some Late Ming Style Ancestral Paintings in Scandinavian Museums’, The Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities Stockholm Bulletin No.70, 1998.