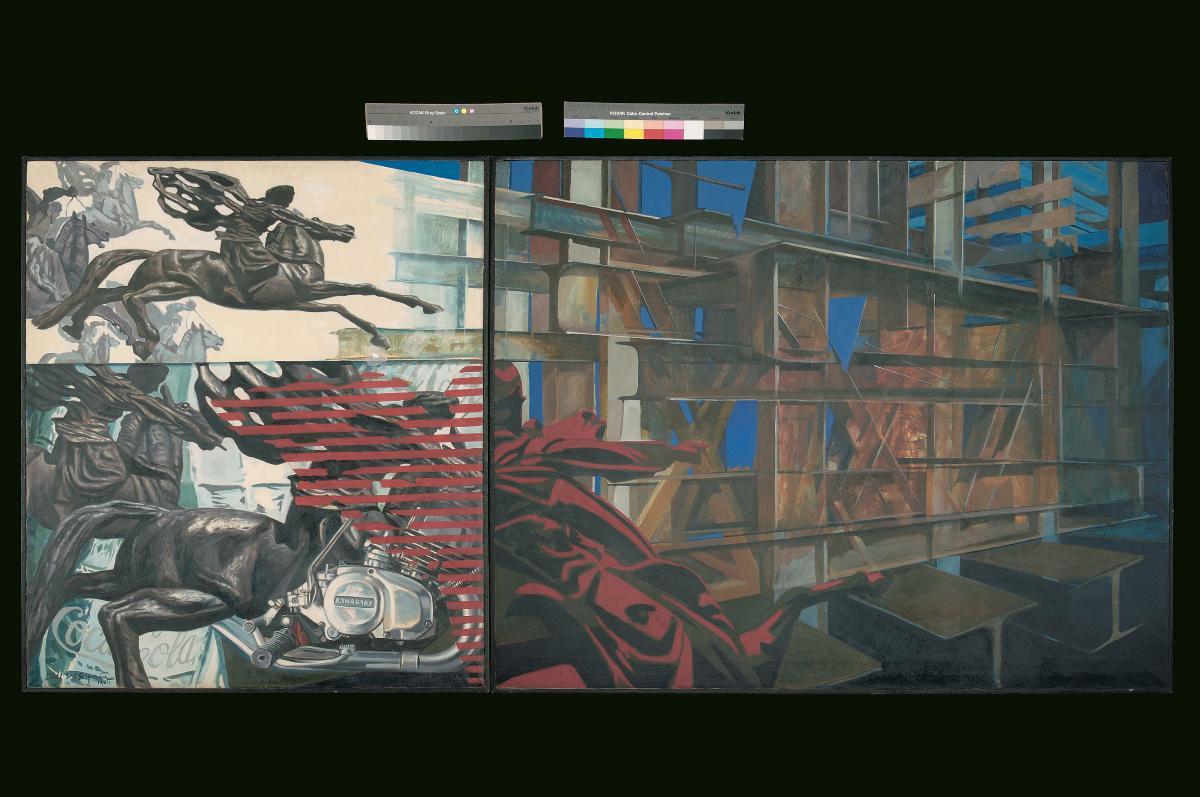

This seminal work shows the maturity of hyper-realist style, introduced by Dede Eri Supria as one of the proponents of the New Art movement (Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru) in Indonesia in the late 1970s. This hyper-realist or Neo-Surrealist style (this term was coined by Jim Supangkat) pushed the boundaries of realism that appropriated from popular culture such as comic strips in how this painting is composed in three frames in sequence. Diponegoro is heralded as a national hero in Indonesia for resisting the Dutch in the Diponegoro Revolution (1825-1830). The image of Diponegoro riding on a horse that transforms into a Kawasaki motorcycle that hurtles into a jungle of steel critiques how rapid changes in society in the name of national development has resulted in many social problems that needs to be addressed nationally. (By Seng Yu Jin)This visual representation of movement is one of the most unique features of this painting if compared to Dede Eri Supria’s other works which mostly capture frozen moments of urban life. The theme of this work, however, is in line with his 1980’s works, i.e., a critical commentary on developmentalism, especially in creating inhumane urban environment. The image of coca-cola bottle as representing global consumer products has been consistently used in Dede’s previous and also his later works. The 1980s was the era of fast-pace developmentalism and neoliberal globalization, spurring high rise urban environment and consumptive life style. The painting expressed his vision of what the country was heading at. “Diponegoro” also relates to Supria’s work on other Indonesian national figures, such as Kartini, Indonesian women emancipation heroine in a painting called “Gincu untuk Ibu” (“Lipstick for Mother”, 1981). “Diponegoro” resembles the painting of Kartini in its strong political commentary, and its metaphorical use of objects. The coca-cola bottle and the Kawasaki motorcycle functions the same way as the hair salon gadgets and cosmetics that confines the women emancipation heroine. Dede agreed that Diponegoro was made during his “symbolic phase”. He said that symbolism was an implicit strategy to do a political commentary, as the State censorship was then very harsh.Another value of “Diponegoro” is its intertextuality and continuation of a genealogy in Indonesian art history. The painting reminds us of a famous and memorable classical painting by the father of Indonesian modern art, Raden Saleh, called “The Arrest of Diponegoro”Raden Saleh’s painting of Diponegoro depicts the historic moment, in which the Javanese prince was captured by the Dutch colonial regime after a set-up negotiation.Yet, Supria’s “Diponegoro” does not directly refer to Raden Saleh’s painting, but to a bronze monument of Diponegoro, with his Islamic headgear, his man blown by the wind, placed in front of the National Monument, across the presidential palace. The bronze statue was not made by Indonesian, but Italian sculptor Cobertaldo, as a gift by then Italian Consulate General, Dr. Mario Pitta in 1965. Supria’s “Diponegoro” – in multiplying copies of the Italian-made statue -- puts this national and transnational connection into play. (By Melani Budianta)