Text by Dr Farish A. Noor

Images: Asian Civilisations Museum

BeMuse Volume 3 Issue 4 – Oct to Dec 2010

Let us begin by asking ourselves a rather simple, if mundane, question: Why is it that when we survey the vast repertoire of batik styles and motifs we often come across certain patterns that are rather loud and crude in the manner they are rendered? And how come some of these patterns – such as the parang rusak or ‘broken sword’, which happens to be one of the ‘larangan’ (forbidden) patterns traditionally restricted to the royalty and aristocracy – were regarded as special and their use limited to the exclusive confines of the palace?

Numerous theories have been advanced to explain this discrepancy in style and taste, and this article does not in any way claim to hold the final answer to the riddle. However we propose that in order to answer the question we need to remind ourselves of what batik is and how it ought to be understood – and more crucially read – as more than just pieces of hand-waxed and painted cloth, but rather as narratives containing statements about the wearer of the batik and the world around him or her. Batik is, in short, a form of visual and textual narrative that can be read (after all, batik is written, remember1) and the answers to the questions that it poses before the eye of the modern viewer can be found in the material itself.

BATIK IN TIME, SPACE AND SOCIETY

First of all, let us situate batik in its proper historical-social context: Like language, batik was the lingua franca of the peoples of Southeast Asia and batiks produced in Java and Sumatra were eagerly bought and used by not only the Javanese and Sumatrans but also the communities of the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Sulawesi and other parts of the Malay archipelago.

However it is to Java that we need to turn to if we are to locate batik in its original setting where the motifs and patterns of the cloth are to be understood and deciphered properly. For it was in Java – particularly between the 18th and 20th centuries – where a highly complex and plural cosmopolitan society emerged that was internally differentiated along the lines of class, wealth, political status and loyalties, ethnicity, language and religion. And in this overdetermined social environment where symbols and markers were constantly being contested and in a state of flux that the motifs and patterns of batik were used as markers of identity and difference.

Elsewhere, we have talked about batik as a marker of ethnic, class, gender and religious identity. But in our attempt to understand and account for the variations of patterns and motifs, and why some were bolder and cruder while others were finer and softer, we need to understand the complex web of social relations and the social hierarchies that were dominant in Javanese society then.

For a start, let us go back to our first question above: Why is it that some of the restricted ‘royal’ patterns and motifs seem cruder than their socially inferior counterparts? Of course it beggars belief to suggest that the Rajas of Java could not afford the finest batiks of the land; and it goes without saying that the workshops and ateliers of the royal houses did produce some of the most sophisticated batiks of Central and Eastern Java. So, why were patterns like the parang rusak deemed preferable to kings, nobles and aristocrats?

THE FABRIC OF A COMMUNITY

Answering such a question necessitates some imagination on our part, and having to imagine how batik was worn, and where and why. The bane of batik research today is the dearth of enough photographic data to show how batik was used on a daily, routine basis by people from all walks of life. In many private and public photo collections, we see batik being worn by those who were clearly posing to be photographed, in situations and settings that were hardly natural.

Nonetheless some leap of faith and suspension of disbelief is required when we try to imagine how batik was worn in the days when it was the common denominator of kings and peasants alike. Living at a time when batik was literally the fabric that held society together and when its use was universal, we need to remind ourselves of the double-faced nature of batik as the universal cloth of Southeast Asia. On the one hand it was the textile that served as the material lingua franca of various communities, but on the other hand, the distinctions between classes, ethnicities, gender and localities had to be inscribed in that same material.

So, if kings and peasants alike wore batik, the only way through which the uneven differentials of power and status between them could be materially reproduced in the public domain was in the material itself, notably its patterns. And in the patterns of batik we may begin to understand the Southeast Asian understanding of the concept of social space, social hierarchy and social distance as well.

CLOSING IN ON AN ANSWER: THE EFFECT OF DISTANCE

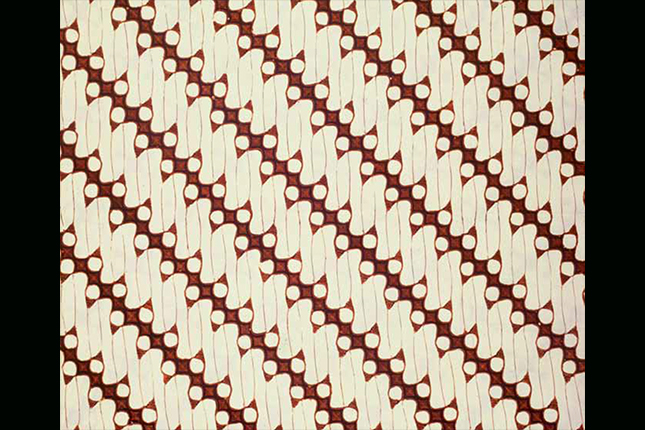

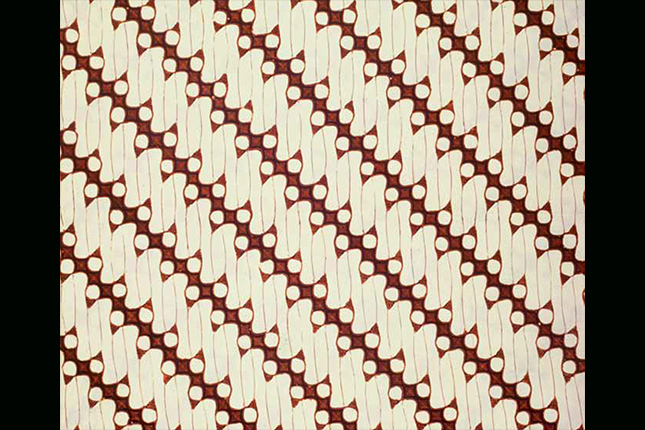

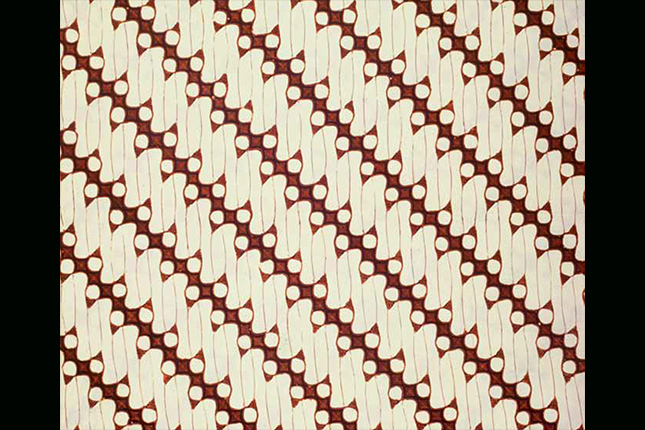

Take a look at a sample of parang rusak below and you may see what I mean: When looked at closely, the motif – a simple, undulating repetitive pattern in a series of broken waves – seems rather crude compared to the sumptuous batiks of Pekalongan, Kedungwuni, Cirebon or Kudus. Some older pieces of parang rusak batik give the impression that they were crudely drawn, almost as if the waxing needle was moved by the hands of an infant playing with a crayon. But therein precisely lies our error: for one is not meant to look at a piece of parang rusak close-up, but rather from a distance, and a respectful distance at that.

Indeed, the intended visual effect of the parang rusak motif is only evident when viewed from a distance (of say, 10 meters or more) and not when it is held in our hands. The same batik which appears crude when held before our eyes has a more arresting effect when viewed from a distance, and this implies that it is meant to be seen from afar; in turn, this implies that spatial distance is part and parcel of the batik’s pattern and effect. This in turn tells us something about the person who wore it (a king or noble) and those who viewed it. From a respectable distance the effect of a parang rusak motif is striking: what appears as a crude representation of broken waves takes on the appearance of graceful undulations that exude order and regularity – precisely the intended effect of the cloth’s pattern and presumably the intended role of the ruling elite as well, who were meant to embody and perpetuate the order of Javanese traditional society.

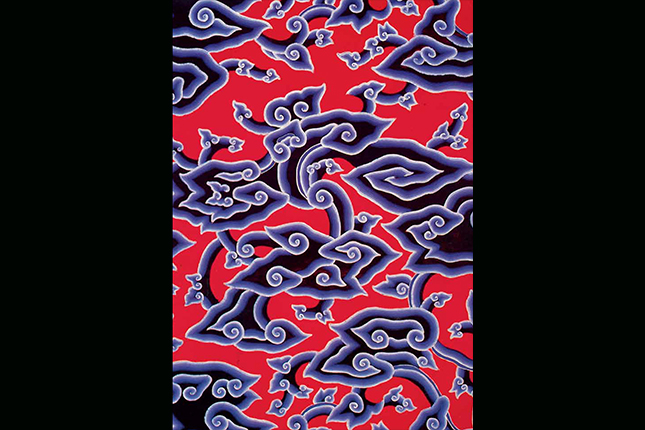

By locating ourselves in the social milieu where batik was worn thus, we begin to understand the complex web of social relations that were crucial to the maintenance of order, social norms and values of this highly conservative and traditional society. It was not an accident that the parang rusak motif was the preferred motif of the aristocracy, in the same way that the mega mendung motif below was likewise the pattern of royal batiks at the court of Cirebon. Both motifs appear crude when viewed up close, but regal and solid from a distance.

Social distancing and the maintenance of social hierarchies were thus part of the function of batik in traditional Javanese society, and such batiks made sense to those who lived in the context of a traditional society where the repertoire of symbols would be available to those who understood how to decipher its hidden meaning.

Such sartorial restrictions – and the social norms and praxis that accompanied them – did not apply to the communities of the north coast where there were no royal houses to set and maintain the standards of society. And in such a milieu, batik motifs and patterns played an altogether different role as they were markers not of social distance but rather social proximity and familiarity.

THE PESISIR BATIKS: A REVERSAL OF SPATIAL AND SOCIAL RELATIONS

The north coast ports and cities of Java were somewhat different from the royal capitals of Central Java as they had initially been small coastal settlements that only later rose to prominence as a result of colonial rule, international commerce and the settlement of many diverse diasporic communities including Europeans, Chinese, Indians and Arabs. Here a different sort of batik emerged as a result of the melange of different cultures that came together within the ambit of colonial race relations and a different mode of social ordering that was the result of mercantilism and transnational linkages. In time the batiks of the north coast cities would become the norm for most Javanese who lived in the more modern and cosmopolitan urban centres and they would gain recognition from other colonial centres including Malacca, Singapore, Penang and as far as Manila and Bangkok.

The social order of these hybrid colonial settlements was entirely different from that of the royal capitals where social hierarchies were accompanied by their own mode of social distancing and spatiality. The absence of traditional values and norms, as well as the sartorial rules and regulations that maintained the social order in traditional Javanese society meant that the inhabitants of these hybrid cosmopolitan centres could mingle with relative ease and inter-ethnic and inter-religious marriages and relations were not uncommon.

It should also be added that the political economy of these coastal port-cities was dependent on international commerce and not the traditional agrarian based economic production model that was the norm in central and eastern Java. As such, the standards that dictated the hierarchies of class and status were somewhat different, and the notion of cultural capital – which often brings with it the weight of history and patrimony – did not apply as much in these new social settings. As many of the wealthier members of such coastal settlements were self-made millionaires whose fortunes depended on trade and manufacturing, social markers of distinction in such settings were more often determined by the markers of capital and economic largesse. The new elite in places like Kedungwuni, Pekalongan, Kudus, Surabaya, Indramayu and Jepara were the landed merchant classes; and in some places – like Kudus, the centre of the hugely profitable kretek (clove cigarette) industry – the wealthy merchants had plenty of money to spare on land, furniture, automobiles and of course batik.

MADE FOR A CLOSER LOOK

If traditional central Javanese batik established social distance and hierarchies through a repertoire of restricted patterns that were meant to be viewed at a respectable distance, no such scruples applied in the cities of north coast Java. The opposite seems to have been the case, with batik producers in places like Kedungwuni, Pekalongan and Kudus producing batiks of such intricate detail that much of the finesse and sophistication is lost to the naked eye when the cloth is viewed from any distance beyond an arm’s length. Indeed, one can only appreciate north coast batiks at their best when looking at them as closely as possible.

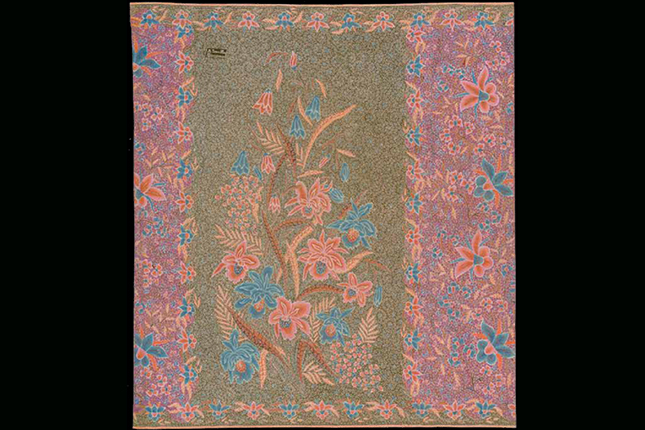

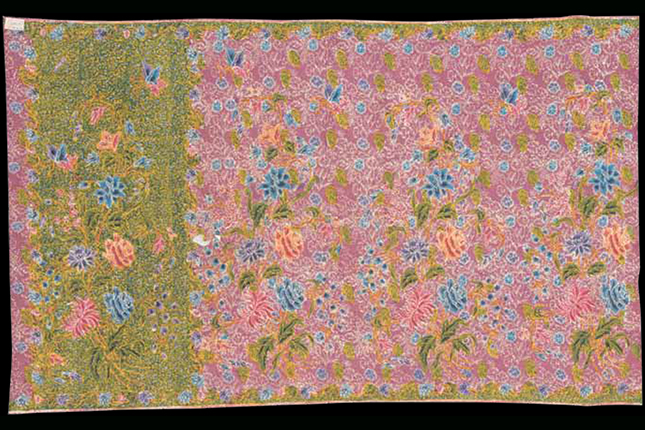

Let us compare two pieces of batik from the north coast of Java below. Seen from a distance of more than three metres, both tubular batik sarongs appear similar in appearance, composition and quality. The finery of the work and the detailed craftsmanship are lost when they are seen from a distance.

However, again we come to understand the meaning and value of such batik when we place ourselves in the same situational context in which they first appeared and were worn. Such batiks were made for women, and it has been established that social relations, networking and interaction among women in the colonial settlements were more relaxed than they were for Javanese women in the royal capitals. As such, one can imagine how and when such batiks were worn by the Eurasian, Chinese, Indian and Arab Peranakan women of the coastal towns; presumably during women-only gatherings like tea parties, lunches or the odd game of mah-jong.

It is precisely during such close encounters that the women of these Peranakan coastal communities would be able to stand literally next to their friends and/or rivals, and at close glance fully appreciate (or in some instances, envy) the elaborate details and ne workmanship of the batik worn by the person standing or sitting immediately next to her. One can only imagine the unstated tension and intense competition of batik aficionados who were determined to out-do their rivals at such gatherings, and the chagrin of the Madam who discovered to her horror that her sworn adversary had managed to get her hands on a priceless piece of batik from the workshop of Oey Soe Choen or Eliza van Zuylen! Such a discovery, however, could only be made up close, when both competitors were sitting eye-to-eye in front of each other...

THE DETAILS THAT MATTER

Now let us look at the two batiks again. The first happens to be a fine piece which was painstakingly hand-drawn with the aid of a canting, a wax pen used to draw ink onto the fabric (fig. 4a). The second is a run-of-the-mill batik from one of the many non-descript factories which churned out large volumes of batik for mass consumption, of standard value and presumably commanding a standard price (fig. 5a).

In an interesting inversion of the social rules of traditional Central Javanese society, the batiks of the north coast display an almost uniform character: despite the fact that they were produced in locations as far apart as Batavia (Jakarta) and Surabaya, the most common motif happens to be the somewhat static and monotonous buketan (bouquet) that was inspired by European oral motifs probably copied from children’s drawing books or fashion catalogues imported from the West. Yet the difference between these batiks lie not in their overall format and composition but rather in the rendering of the flowers, birds, bees and butterflies we see in them, rendered in varying degrees of detail ranging from the crude and elementary to the mind-bogglingly precise and microscopic.

This difference in detail in turn served as the benchmark whereby the value and price of such batiks were estimated and sold, with the most detailed pieces commanding the highest prices. Needless to say, in wealthy circles such as those found among the merchants of Batavia and Kudus – as well as Bantam, Singapore, Penang and Malacca – the most expensive batiks that were produced by the workshops of the Pesisir soon found a ready market and a happy home for themselves.

In summing up, we need to remember that batik has to be understood in the situational context in which it found itself, and that understanding the meaning and import of batik motifs and patterns requires some understanding of how batik was situated in extended spatial-social relations where it could perform the social function it had: as a means of establishing social distance and proximity, and a way of keeping everything and everyone in their place. No mean feat for a piece of cloth.

1 Batik is written in the sense that we write it with a wax pen canting, not painted with a brush. Also until today in parts of Java the word batik literally means to write, as in ‘batikin nama bapak dalam buku ini’.

Dr Farish A Noor is a Senior Research Fellow at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU; and has been collecting batik from all over Southeast Asia for more than a decade now. He is one of the co-authors of ‘The Spirit of Wood: The Art of Malay Traditional Woodcarving’, along with Eddin Khoo.