TL;DR

Did you know that before sites and buildings are identified as historically significant, it starts with an inquisitive explorer who literally walks around Singapore to discover them? While heritage lives all around us, it sure takes an experienced researcher like Ching Huei to recognise and study them!

MUSE SG Volume 15 Issue 01

Read the full MUSE SG Vol 15, Issue 1.

Watch: Meet Heritage Researcher Ng Ching Huei

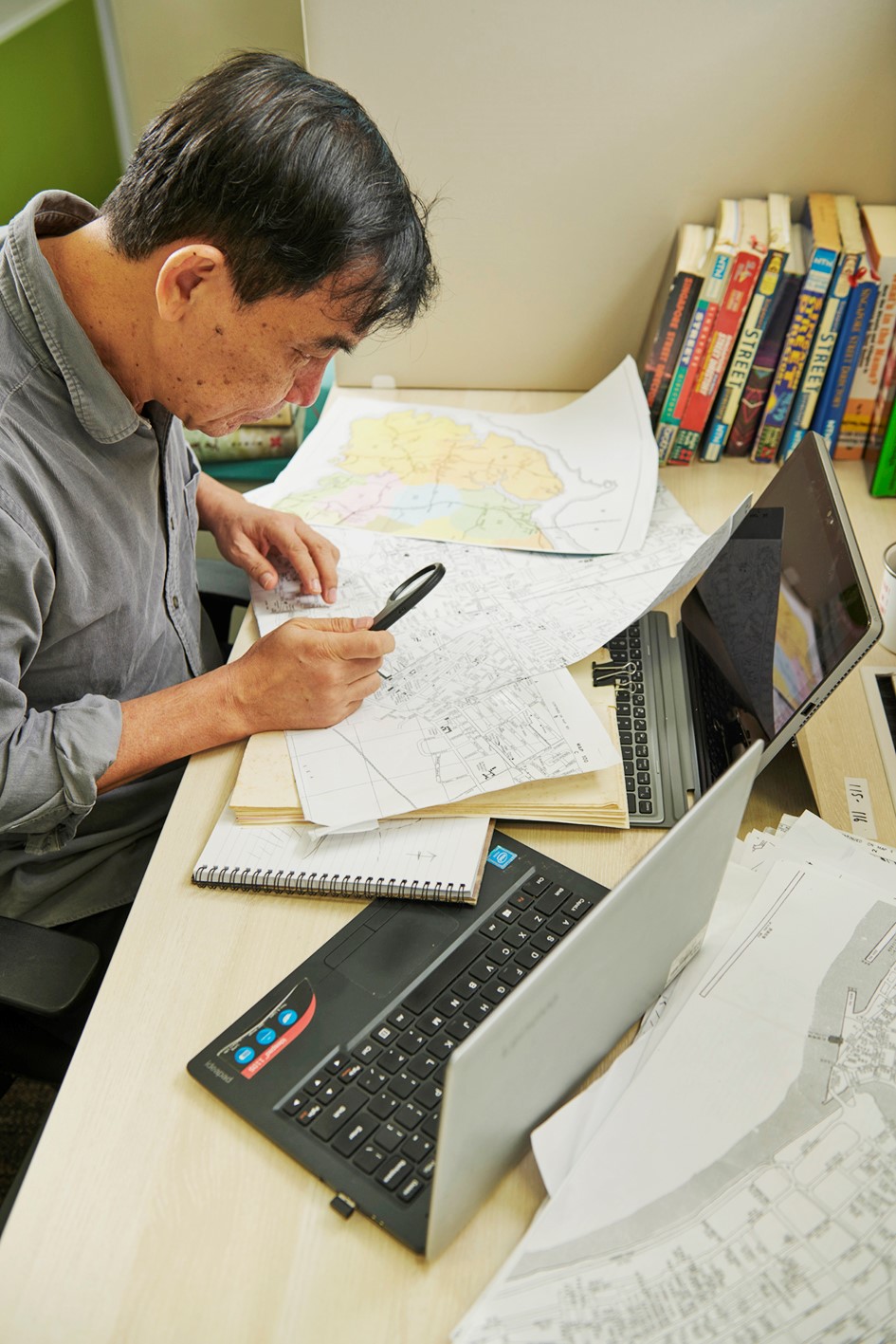

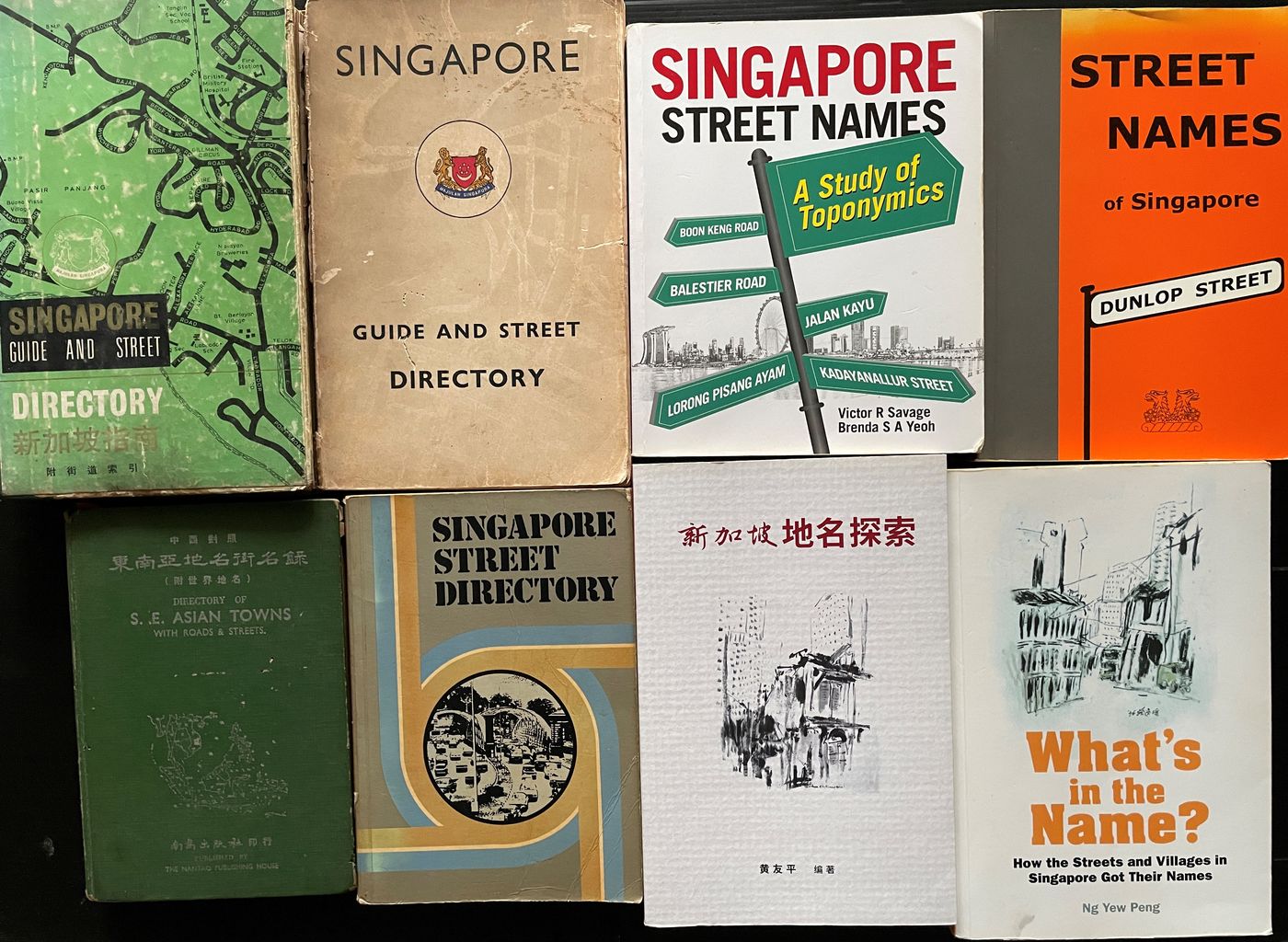

Ng Ching Huei has spent over two decades with the National Heritage Board (NHB), joining the statutory board mid-career. A witness to the transformations of the local heritage sector, Ng is a living repository of information. He started out in the 1980s as a participant with Friends of the Museum and became a volunteer guide in 1997.

Today, Ng primarily works on a database that maps heritage sites in Singapore—providing an invaluable tool for NHB researchers and government urban planners. MUSE SG speaks to Ng about his life in heritage work, and finds out what continues to thrill him after all these years.

Can you tell us how you got your foot in the door of heritage work?

I joined NHB quite late as a second career. Before that I’d spent 15 years at the Ministry of Defence, also doing research work. However, I recall that even when I was in the army, every Friday I would attend a talk by Friends of the Museum.

I subsequently became a volunteer with Friends of the Museum. From there, I got to know [archaeologist] John Miksic and joined him in a project at Kampong Gelam, sorting and labelling archaeological items. Due to my involvement with such projects, I met some curators from the then Singapore History Museum [now National Museum of Singapore], and was recommended by Miksic to Iskander [Mydin; then Senior Curator of the Museum and now Curatorial Fellow], who offered me a part-time position with the Museum’s curatorial team. Subsequently, I joined the Museum as a fulltime staff.

Knowing that you entered the heritage sector later in your career, how did your seniority prove advantageous in your work?

One of my early projects was with Chinatown Heritage Centre. At the time, museum exhibitions were shifting to ‘contextual displays’, where we tried to recreate scenes from the past. We collected as many ‘living’ objects as possible to display in contextual manner.

Together with Lim Guan Hock (former Deputy Director, Special Projects, of Singapore History Museum), we went around collecting artefacts for the Singapore History Museum’s Folklife Collection. I was 40 years old at the time and was working with colleagues who were much younger. My age gave me an edge as I had the language skills to communicate more easily with the elderly individuals, and therefore I was tasked with handling acquisitions.

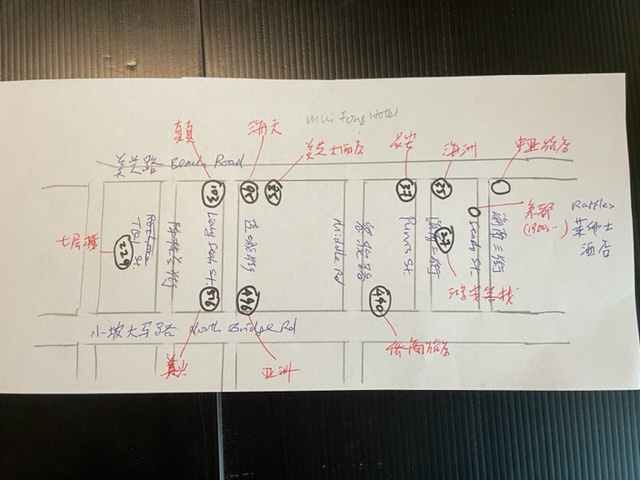

Another instance where my ‘seniority’ came in useful was a project I was involved in to catalogue materials such as photographs and postcards. We had to go through the collection and tag the items with descriptive information. I found it much easier to identify places in the images and on maps compared to the younger colleagues, and I suppose it was because I’d witnessed a lot more of the landscape transformations.

With over two decades of experience in heritage work, what are some of the greatest transformations you have witnessed in the museum sector?

I think one of the greatest changes pertains to staff strength and the volume of heritage programmes. Before 2003, there were only about 10 or 12, at most, 14, staff at the Singapore History Museum. When the public approached the museum for advice, there used to be only one person to handle everything.

There were very few programmes in those years—one exhibition, followed by one or two public programmes. But things started to expand from 2003 onwards: Every department had more people, and thus there were more programmes such as children’s programmes, and public outreach. Researchers now have the opportunity to share their findings.

Today, the scope of museums is also much wider and more comprehensive. Over the years, the presentation of artefacts was honed and improved, leading to today’s multi-encompassing form of curatorial presentation, which includes the digital aspect. The museum is no longer traditional; instead, it adopts a ‘softer’ approach. For example, the National Museum embarked on a thematic approach in 2005, with different galleries for fashion, food, etc.

“When the stories of our present-day buildings and sites are put into context and they become part of our daily life, we will find that life is more meaningful. "

What got you interested in heritage work? And what sustains your interest today?

I find heritage research to be akin to detective work, like solving a jigsaw puzzle. I enjoy connecting the dots and putting things together to tell a story. For instance, someone recently donated an old hawker licence. I tried to interpret the story based on the item. Every word and detail on the artefact provides a clue to understanding the object; with the right amount of research, we can then start to piece together the historical context. You begin to feel that everything is connected. From a simple hawker licence, you can link it to the hawker’s dialect group, social connections and other stories. It is a very exciting process!

What makes it tremendously fulfilling is then sharing these stories with the younger generation who might not know what the hawker licence means and what it tells them about their grandparents. I find it very meaningful to meet people and share information with them. Finally, heritage is a crucial part of life, and it sparks good conversations!

What is your favourite part of work?

The best thing I like about my work is the many opportunities to visit forested or limited-access areas in Singapore to discover forgotten buildings, military structures, hidden graves and boundary markers. After gathering more information to enliven the history of these sites, we add it to our database and plot it on the map. Thus, we not only rediscover and reconnect with the past, but also enhance our database of heritage sites in Singapore!

Is there an artefact or a place that you cherish deeply?

Personally, I like to trace cityscape changes. I live in the town area, so I am particularly drawn to the sites around me. These include the Singapore River, Chinatown, Little India and Kampong Gelam. The historical districts are my favourite places. I find out about the different styles of shophouses and their classification, and learn how to identify them. When the stories of our present-day buildings and sites are put into context and they become part of our daily life, we will find that life is more meaningful.