Image Above: (Fig. 1) The set of jewellery that was handed down four generations of the Montilla clan. A set of jewellery, Philippines, c. 19th-20th Century, Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum

MUSESG Volume 15 Issue 1 – January 2022

Text by Naomi Wang

Read the full MUSE SG Vol 15 Issue 1

In 2020, the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM) received a gift of Philippine jewellery from the Montilla clan, one of the earliest settler families in Negros Occidental, Philippines. Handed down four generations, this is a significant donation as it furthers ACM’s mission in promoting cross-cultural art and sheds light on centuries of goldsmithing and trade in the Philippines.

The Montilla Clan

Josefa Jordan Ortaliz (birth and death unknown) was the daughter-in-law of the family’s patriarch, Agustin Orendain Montilla (1802–?), a Philippine-born Spaniard who married Vicenta Locsin-Zarandin Yanson (1807–?), a mestiza from Iloilo.1 Ortaliz bequeathed her jewels to her eldest daughter, Lina Ortaliz Montilla (1868–1939), and she thence to her daughters, Lilia Montilla y Montilla (1901–83) and Lina Juana Montilla y Montilla (1906–85).

(Fig. 2) Lina Ortaliz Montilla (1868–1939) and her first cousin and husband Candido Montilla (1871–1943). Philippines, circa 1931. Photograph. Private collection.

(Fig. 2) Lina Ortaliz Montilla (1868–1939) and her first cousin and husband Candido Montilla (1871–1943). Philippines, circa 1931. Photograph. Private collection.

From the Montilla sisters, the jewels were passed down to their niece, Corazon Arroyo Montilla (1933–2021). Separately, a pair of diamond earrings were gifted to Corazon for her high school graduation from her grandaunt Doña Leoncia Lacson y Torres (1903–81). The latter had received the earrings from her father, General Aniceto Lacson y Ledesma (1857–1931), who served as president of the shortlived Republic of Negros in 1899.

Agustin Orendain Montilla relocated to Negros Island from Manila to set up an agricultural settlement in Pulupandan. He grew a variety of crops, including rice, abaca and maize, and later became one of the first to produce sugar on a commercial scale in the Philippines.2 Negros Island became a dominant player in the world’s sugar economy in the 19th century.

(Fig. 3) The Montilla family crest with lineage from Córdoba, Spain (reproduction). Philippines, 1950s. Paper, ink. Private collection.

(Fig. 3) The Montilla family crest with lineage from Córdoba, Spain (reproduction). Philippines, 1950s. Paper, ink. Private collection.

Composed of thousands of islands, the cultural fabric of the Philippines is diverse. The Negrenses from Negros Island are proud of their distinct culture and language. On the island, two main languages (different from Tagalog) are spoken: Hiligaynon in the province of Negros Occidental (northwestern Negros Island), where the Montilla family settled; and Cebuano in Negros Oriental (southeastern Negros Island).

Beyond Manila: Multiple Centres of Commerce

“From China come many persons able and willing to engage in all sorts of trades and they are skilful, quick and economical. They are… tailors, the shoemakers, and the silversmiths, the sculptors… and they take over all classes of work in the city.”—Fr. Pedro Chirino3

Historically, the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean served as natural conduits for cross-cultural interaction between individuals of various faiths, cultures and occupations.4 Even before the 1521 arrival of Spanish conquistadors in the Philippines, multiple centres, such as Cebu and Iloilo (on either side of Negros Island), had been flourishing ports with developed settlements. Under Spanish rule, these centres continued to evolve due to intensified global interaction.

From 1571 to 1815, the galleon trade made Manila’s walled city, Intramuros, one of the main entrepots of the world.5 From nutmeg from the Moluccas to coral from the Mediterranean Sea, the world’s luxury goods converged in Manila’s multicultural trading hub, where pidgin Hokkien or pidgin Spanish with Tagalog elements developed in the course of daily encounters.6

(Fig. 4) The Montilla ancestral home known as Balay Daku (‘big house’ in Hiligaynon), built in 1853. Negros Island, Philippines. Photograph. Private collection.

(Fig. 4) The Montilla ancestral home known as Balay Daku (‘big house’ in Hiligaynon), built in 1853. Negros Island, Philippines. Photograph. Private collection.

It was against this backdrop of mercantile activity that the exchange of goods and ideas occurred. The racial hierarchy imposed under Spain’s colonial rule placed Peninsulares (Spaniards born in Spain) on top and Indios (indigenous inhabitants of the Philippines) at the bottom.

However, this did not impede interactions between people of different classes and ethnic backgrounds. It was in the Parian, a Chinese-designated area outside the walled city of Manila, where the Spanish made their orders, and where itinerant artisans produced objects according to the varied tastes of customers, further fuelling artistic exchange and creativity.7

From the 16th century, Spanish accounts have noted the impressive command of techniques by local goldsmiths. Multiple centres for jewellery production soon developed, drawing large numbers of local and foreign goldsmiths to areas beyond Manila, including Luzon Island, Damortis in the province of La Union, and Vigan and Bantay in the Ilocos Region.8

The influx of local and itinerant smiths contributed to the hybrid nature of Philippine jewellery. The abundance of silver due to the galleon trade attracted Chinese silver artisans from Guangzhou and Fujian, where the famed Chinese silver export market had been established in the latter half of the 17th century.9

By the 19th century, descendants of these immigrant artisans had assimilated into Philippine society, and were working in a style heavily influenced by European demand and the varying tastes of local communities.10

Practical Liaisons: Mixed-race Marriages and Hybrid Tastes

In the 17th to 19th centuries, travellers to Asia often recorded observations of racially hybrid communities in port cities.11 Mixed marriages such as that between Montilla and Yanson, were practical: they allowed foreign businessmen to access Asian networks and grow commercial opportunities, as the local wives could speak several languages and understand two or more cultures.12

As ‘cross-cultural brokers’, mixed communities became indispensable in trade and politics.13 It was against this backdrop of cultural and religious mixing that indigenous communities, Christian Chinese, and mestizos of mixed Spanish, Chinese and Indios origin, developed hybrid forms of art and manners of dress.14

(Fig. 5) Portrait of Josefa Jordan Ortaliz Montilla based on a photograph from the 1890s. Fernando Amorsolo (1892–1972). Philippines, 1950s. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

(Fig. 5) Portrait of Josefa Jordan Ortaliz Montilla based on a photograph from the 1890s. Fernando Amorsolo (1892–1972). Philippines, 1950s. Oil on canvas. Private collection.

Josefa Jordan Ortaliz married Montilla and Yanson’s oldest son, Bonifacio Yanson Montilla (birth and death unknown), in 1867.15 A portrait of Josefa based on a photograph from the 1890s shows the hybrid dress of a wealthy mestiza (Fig. 5). Notably, a large gold peineta (comb) holds her chignon in place.

Peinetas were used until the mid-20th century, and were eventually made obsolete as shorter hairstyles became de rigueur. While tortoiseshell combs were popular in Spain by the 19th century, crescent-shaped combs are Chinese in origin, and the Spanish vogue for tortoiseshell combs was likely due to the Manila galleon trade through Spain’s colonies.16 Two peinetas (see Figs. 1 and 6) worn by Ortaliz are made of gold, silver, tortoiseshell and seed pearls from the Sulu archipelago. These lavish materials reflect the resource-rich bounty of the Philippines.

(Fig. 6) These peineta and veil hairpins illustrate the accomplished work of local goldsmiths. Peineta, Manila, Philippines, c. 1870s, Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum.

(Fig. 6) These peineta and veil hairpins illustrate the accomplished work of local goldsmiths. Peineta, Manila, Philippines, c. 1870s, Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum.

Historically, the Philippines was rich in natural resources beyond gold. Valuable sea products like tortoiseshell and pearls are indigenous to the Philippines. The hawksbill tortoise, now sadly endangered, enabled workshops in Manila to become major producers of luxury products made from tortoiseshell. The trade of pearls is likewise centuries old. As early as 1349, the Chinese traveller Wang Dayuan had observed that “pearls from the Sulu archipelago were prized for their lasting blue-ish white colour, and traded for gold, silver and iron bars”.17

The gold and silver peineta and veil hairpins (Fig. 6) illustrate the accomplished work of local goldsmiths. The undulating outlines of golden flowers and leaves reveal the remarkable ability of local craftsmen to go beyond imitating European jewellery styles, to create objects of great naturalism. During this time, botanical drawings inspired a Victorian fondness for floral and vegetal motifs. In these ornaments, the flowers and leaves capture the essence of life and movement in nature.

(Fig. 6) These peineta and veil hairpins illustrate the accomplished work of local goldsmiths. Veil Hairpins, Manila, Philippines, c. 1870s, Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum.

(Fig. 6) These peineta and veil hairpins illustrate the accomplished work of local goldsmiths. Veil Hairpins, Manila, Philippines, c. 1870s, Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum.

Centuries of goldsmithing knowledge enabled local smiths to work in a wide range of techniques and forms, their skills and inspiration garnered from a myriad of cultures. Oblong criollas (earrings) derived their name from hoop earrings worn by Mexicans of mixed race.18

The form of these earrings has an equally hybrid origin as they take after Spanish ear ornaments, though they originate from styles introduced to Spain by Muslim rulers (the Umayyad Caliphate was in Spain by the 10th century)—hoop earrings appear frequently in medieval Islamic jewellery.19 In Figure 7, we see the rare example of criollas that are each decorated with a bird holding a rice stalk in its beak (criollas embellished with floral and vegetal motifs are more common).

(Fig. 7) A pair of criollas (earrings) with birds. Criollas, Northern Luzon, Ilocos region, c. mid-19th century, Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum Gift of the Montilla Family of Pulupandan, Negros Occidental

(Fig. 7) A pair of criollas (earrings) with birds. Criollas, Northern Luzon, Ilocos region, c. mid-19th century, Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum Gift of the Montilla Family of Pulupandan, Negros Occidental

(Fig. 7) A pair of criollas (earrings) with birds. Criollas, Northern Luzon, Ilocos region, c. mid-19th century, Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum Gift of the Montilla Family of Pulupandan, Negros Occidental

(Fig. 7) A pair of criollas (earrings) with birds. Criollas, Northern Luzon, Ilocos region, c. mid-19th century, Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum Gift of the Montilla Family of Pulupandan, Negros Occidental

European Religion and Superstition in Philippine Jewellery

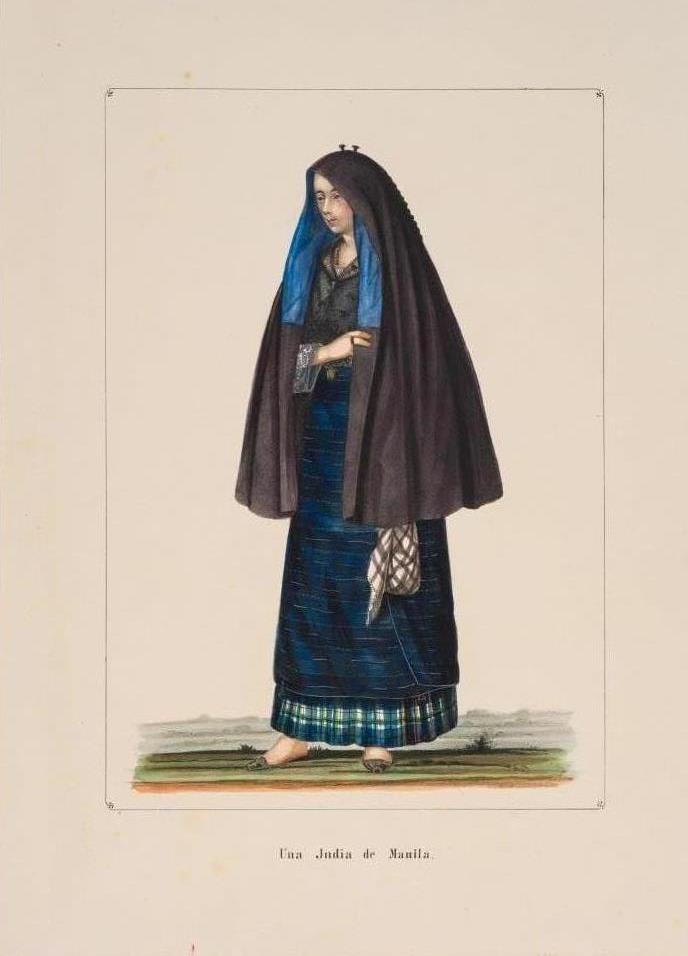

In accordance with the Montilla family tradition, Ortaliz passed down her jewellery to her eldest daughter, Lina Ortaliz Montilla. The popularity of veil hairpins in the Philippines is in large part credited to the adoption of Spanish dress. They were used to secure prestige accessories like the lace pañuelo (veil), which wealthy native and mestiza women wore to church as an indication of modesty, religious devotion and upper-class status.20

Devotional jewellery played a central role in Philippine dress. Beyond religious piety, Christian ornaments indicated an allegiance to Spanish rule and luxurious ones conveyed social status. Religious jewellery from the Philippines, though taking after Spanish examples, have their own distinctive character and gradually evolved to adopt a native style.

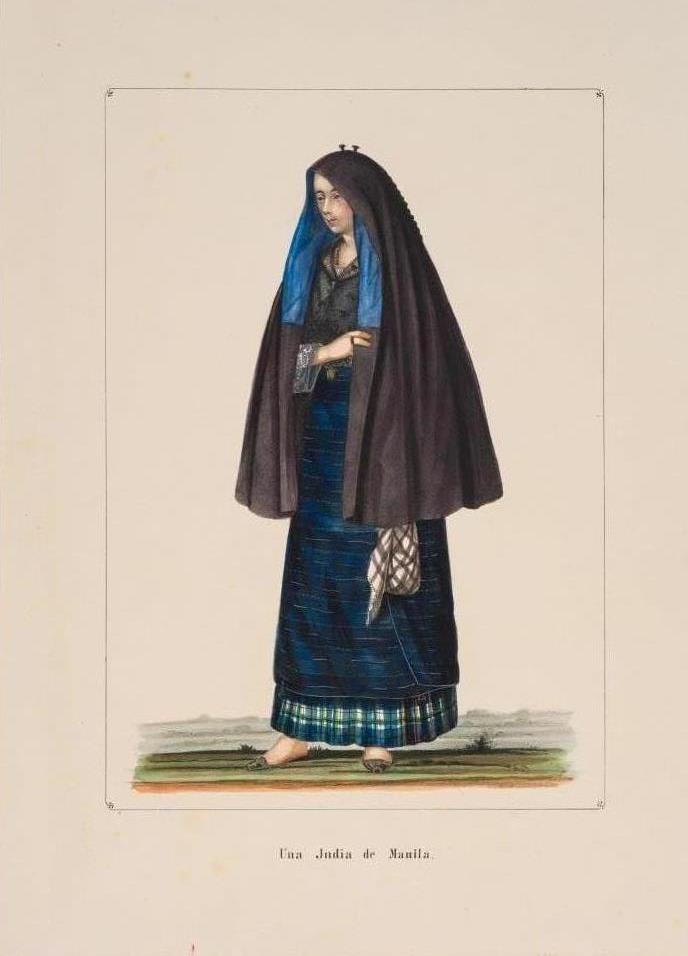

(Fig. 8) Lithograph of a mestiza wearing a veil with hairpins. Una India de Manila, Philippines, c. mid-19th century, Collection of National Gallery Singapore

Undoubtedly, other influences—from the Chinese, for instance—also played a key role in trade and goldsmithing in Manila.21 The centuries-long Chinese–Philippine interactions are evident in how natives in the Philippines used Chinese terms for gold weight, tools and techniques long before Spanish arrival.22

In Figure 9, we see a gold bead on the coral rosary which is decorated with stylised Chinese character 寿 (shou), which refers to ‘longevity’. Jewellery with highly prized coral beads (see criollas with coral beads in Fig. 1) were a marker of luxury, and they reflect the trading port status of the Philippines. Because Manila was a doorway to the global trading world, luxury commodities like coral were made available to its wealthy residents.23

(Fig. 9) A gold bead with the stylised Chinese character 寿(shou), meaning ‘longevity’, on a rosary. Gold bead, Philippines, late 19th or early 20th century, Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum Gift of the Montilla Family of Pulupandan, Negros Occidental

(Fig. 9) A gold bead with the stylised Chinese character 寿(shou), meaning ‘longevity’, on a rosary. Gold bead, Philippines, late 19th or early 20th century, Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum Gift of the Montilla Family of Pulupandan, Negros Occidental

The use of llaveros (keychains) was also common throughout the Philippines, Java and the Straits Settlements. In the later decades of the 19th century, ringed key hooks modelled after European examples became fashionable.

A popular form involves a key ring suspended from a clenched fist, referred to as figa (derived from the Latin ficum facere). It is symbolically linked with the fig and signifies life. The figa is known in various cultures throughout antiquity, among them the Egyptians, Phoenicians and Etruscans, who used this symbol as an amulet. In Spain, the figa functioned as an amulet against the evil eye and was worn by children. For grown women, the phallic shape of the figa alludes to ideas of fertility.24

(Fig. 10) Key ring with figa (clenched fists). Such ringed key hooks became fashionable in the later decades of the 19th century. Key Ring, Philippines, late 19th or 20th century, Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum Gift of the Montilla Family of Pulupandan, Negros Occidental

(Fig. 10) Key ring with figa (clenched fists). Such ringed key hooks became fashionable in the later decades of the 19th century. Key Ring, Philippines, late 19th or 20th century, Collection of Asian Civilisations Museum Gift of the Montilla Family of Pulupandan, Negros Occidental

A large quantity of Chinese jewellery found in the 1638 wreck of the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción (a Manila galleon bound for Acapulco) includes several jewels with this clenched-fist motif. This attests to the widespread circulation of the figa motif and its global use spanning centuries. In the same way that the crescent-shaped peinetas were likely brought to Spain from China through its colonies, it is possible that the Portuguese and Spaniards introduced the figa symbol to their colonies in Southeast Asia.25

From China to the Philippines and from Mexico to the Iberian Peninsula, networks of conquest, trade and migration impacted the cross-cultural and hybrid characteristics of Philippine jewellery—and this set of jewellery from the Montilla clan is a gleaming example of that. Unearthing the provenance of these historical gems allows us to understand the culturally fluid reality of the Philippines during the 19th and mid-20th centuries, and, no doubt, their donation to ACM will contribute greatly to the study of Philippine history and material culture.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Corazon Arroyo Montilla who passed away on 11 June 2021.