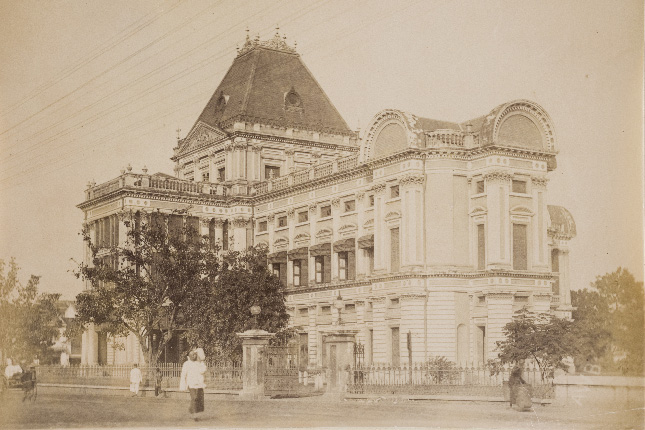

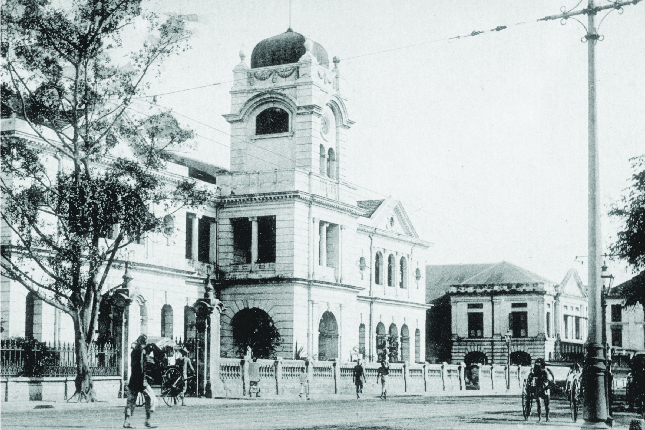

The British built many buildings in the 1880s, including the elaborate, French-style Police Courts on Dunman’s Green (renamed Hong Lim Green in 1892, present-day Hong Lim Park), opposite the Central Police Station along South Bridge Road. Expecting crime to be on the rise due to growth of Singapore as a trading port, the Police Courts was completed in 1885, handling a myriad of crimes for 90 years. Like other police establishments and medical institutions, it was located outside the European town where crime was expected to be more prevalent.

Early Justice System

Singapore’s earliest judicial system was established when Major-General William Farquhar, the first Resident, co-opted two Malay chiefs and began holding weekly court sessions.

In 1823, Sir Stamford Raffles formalised this rudimentary system by setting up a magistracy and legal administration where magistrates were appointed to assist the Resident to hear petty criminal and civil cases based on the principles of English law with modifications in view of local customs and habits.

The judicial system underwent many changes and alterations in the decades that followed. When Singapore became a crown colony in 1867, the Law of England remained the basis of the legal system, with provisions for local laws.

Colonial Police Prosecutors

Until the enactment of the Courts Ordinance in 1907, the Police Courts were known publicly as the Magistrates’ Courts, before it adopted its former name. In 1954, the Police Courts were renamed the Magistrates’ Courts. Court hearings were presided by government-appointed Magistrates, several of whom were prominent community leaders, with police officers as prosecutors. The Inspectors from the various Divisions took on the majority of the cases while officers of the rank of the Superintendent of Police took charge of serious crime cases such as murders. The Inspector-General of Straits Settlements Police (IGP) was only called upon for the most important or difficult cases, such as those connected with secret societies.

Prosecution work added to the already heavy workload of these police officers. Their work was also made more challenging because Police Prosecutors were not trained in law. By the late 1870s, court duties had left the Superintendent of Police very little time for his other supervisory and policing duties. Inspectors were handling so many cases that they often found themselves required at different Courts at the same time.

Seat Of Justice

The location of the Courts, directly opposite the former Central Police Station, allowed officers to escort suspects on foot from the Station’s lockup across the road to the Courts. In 1947, additional court rooms were added to handle the increasing number of cases heard at the Courts.

By the 1970s, the Courts were in need of an upgrade - the courtrooms were not air-conditioned, toilets were unsanitary, and suspects were escorted around in handcuffs in full view of the public. At that time, there was a compelling need to centralise all the courthouses operating from the different locations. In 1975, the courts in the Police Courts building and other subordinate courts moved to the new Subordinate Courts building at Havelock Road (today known as State Courts). In the same year, the Police Courts building was demolished.

The Police Courts witnessed the administration of justice within its chambers for close to 100 years before it was demolished for urban development in 1975. Through the years, the Police Courts symbolised progress, justice and zero-tolerance towards criminality. Hong Lim Park stands in its place now.

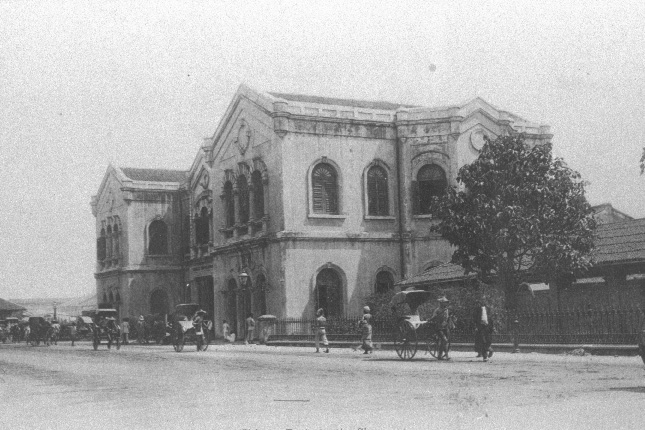

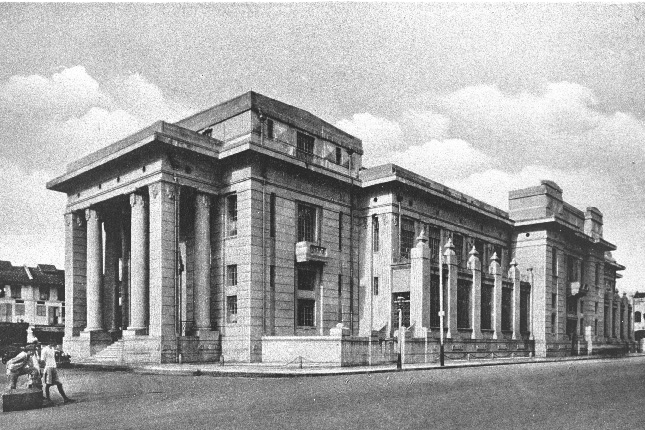

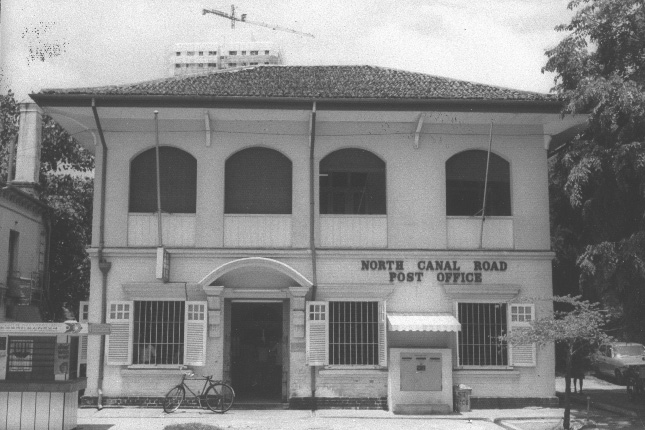

In The Vicinity - Chinese Protectorate

The first office of the Chinese Protectorate was located in a shophouse on Canal Road when it opened on 1st June 1877. On 1st February 1881, the office relocated to shophouses Nos. 16 and 17 on Macao Street (present-day Pickering Street). In August 1885, the Protectorate moved into a commodious building in Boat Quay and again in June 1886, moved to Havelock Road, the site of present-day Furama City Centre. Verandahs were added on three sides of this building in 1888 before it was eventually demolished in the 1930s. The Protectorate moved into a neoclassical-style building next to the old Protectorate building on 22nd November 1930.

After the war from 1956, its responsibilities were taken over by the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare, and later the Ministry of Labour (known as Ministry of Manpower today), which continued to occupy the Havelock Road premises until 1989. Since the 1990s, the building has been used by Singapore’s Judiciary and, coming full circle with its original function to support the vulnerable in society, houses the Family Justice Courts today.

Crime in a Thriving Settlement

For much of the early 19th century, the British relied on indirect rule and community intermediaries to govern the predominantly immigrant population. This led to the rise of Chinese clan associations or ‘hui guan’ which were organised along kinship and dialect lines to provide mutual aid (such as accommodation, job opportunities, financial aid, welfare) to their own communities.

However, the unregulated approach was open to abuses and led to dire social consequences and a rise in crime rates. Clan associations like the Ghee Hin for instance, which was the first to be established in Singapore in 1820, extended their power and influence over their members and through their control of profitable business like trade in pepper and gambier. The associations also controlled vices like opium dens and brothels, which proliferated unchecked. Often, these vices were pushed to the same coolies whom the associations were supposed to support and protect. Due to their involvement in illegal activities, some clan associations later became known as secret societies. When these associations splintered due to power struggles, outbreaks of riots occurred.

In addition, human trafficking and abuse of coolies were rife. Until 1859, it was illegal for a Chinese person to emigrate. Nonetheless, in response to a wide demand for cheap Chinese labour, coolie brokers used unscrupulous means to acquire coolies, at times kidnapping them by force or bonding them to their employers in return for the cost of the journey from China. Some secret societies were involved in this lucrative trade. Cho Kim Sang, the leader of Hokkien Ghee Hin in 1880, was one of the more influential coolie brokers.

Impetus for the Chinese Protectorate

By the 1870s, the city’s social problems became so acute that it finally forced a change of policy. The threat to public order from the Chinese immigrant population and secret societies began to trouble the colonial authorities. For instance, during the Chinese Post Office Riot in 1876, the Teochew towkays collaborated with secret societies to incite the Chinese population to riot. The riot was a protest to the new British post office system that challenged the towkays’ monopoly of remittance posts.

A year later in 1875, the Chinese Protectorate, first mooted by the IGP Samuel Dunlop, was formed to counter the influence of secret societies by providing assistance to the Chinese community. William Pickering, who was a Chinese interpreter for the British and a Police magistrate, was appointed to the post. The Protectorate began its work by regulating the coolie trade and ensuring that new arrivals were fairly treated.

Pickering and the IGP also worked jointly to tackle crime, even observing secret society initiation ceremonies together as part of investigations. The Protectorate was also in charge of overseeing the secret society registrar, which was started by the Police in 1869. It tackled vices such as gambling by investigating the problem and recommending increased regulations. As for prostitution, which was rife in a society with a skewed gender ratio, the Protectorate set up a committee of towkays called the “Po Leung Kuk” in 1886, to help with the refuge of young girls caught in sex trafficking.

Although intended to improve the welfare of the community, the Protectorate encountered hostilities from some segments of the population. Secret societies in particular, mistrusted the Protectorate as it undermined their illegal activities and influence. These tensions reached boiling point in 1887 when a member of the Ghee Hock secret society, angered by an investigation into the bribery of police officers to keep gambling dens open, attempted to assassinate Pickering. He walked into the Protectorate’s Havelock Road office and hurled an axe at Pickering, injuring him badly. The Ghee Hock member was eventually charged but Pickering was forced into early retirement shortly after due to his injuries.

Legacy of the Protectorate

Successors of Pickering continued his legacy in dealing with Chinese immigrants’ matters. Following the attack on Pickering, the authorities stepped up efforts to curb secret societies and outlawed them in 1890. Hand in hand, the Protectorate and the Police continued to combat secret societies. Although secret societies continued to operate underground and enjoyed moments of resurgence especially during the economic depression in the 1920s, their activities were greatly curtailed. The Protectorate continued to work with the section of CID that dealt with secret societies well into the 1930s, when that responsibility was handed over fully to the Police.

The Protectorate eventually became a legitimate alternative for migrants to approach to resolve problems, instead of turning to secret societies. This, combined with better government administration in general, was successful in improving the welfare of immigrants and keeping crime under control until the outbreak of World War II.