Nasi Lemak

Nasi lemak is a rice dish commonly served with roasted nuts, egg, ikan bilis (anchovies), and slices of cucumber. Literally meaning “fatty rice” in Malay, nasi lemak’s distinctive taste comes from cooking the rice in coconut milk and pandan leaves which gives the dish its rich flavour and fragrant aroma. It is rounded off with spicy sambal – a chilli paste made from dried chilies, garlic, shallots, and belacan (shrimp paste).

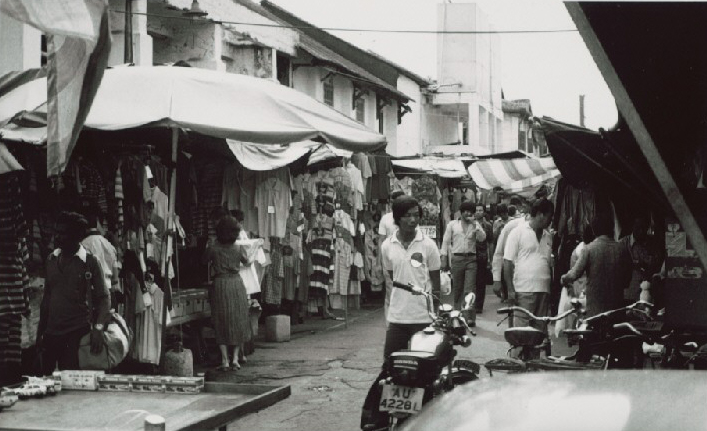

Nasi lemak has roots in Malay cuisine. It is believed to have originated from the indigenous community who lived by the sea on the West coast of Malaysia in the 19th century, where coconuts and anchovies were widely accessible. The dish later became a staple diet for farmers who worked in the rice fields. In the 1970s, nasi lemak was sold in packets by hawkers travelling from house to house.

In Singapore, nasi lemak is a notable Malay dish, and is acknowledged as an important part of Singapore’s food heritage. The dish is sold across Singapore, and some people cook it at home as well. Although traditionally consumed during breakfast, the dish is now eaten for breakfast, lunch, dinner and supper.

Geographic Location

Today, nasi lemak is commonly found in food stalls of hawker centres and food courts in Singapore. It can also be found in some restaurants and hotels. Nasi lemak has also managed to make its mark internationally. For example, nasi lemak was featured in the Singapore Day events in various cities around the world, and at Singapore food events overseas. The dish can also be found in other countries in the region, including Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei.

Communities Involved

Nasi lemak is enjoyed by Malays and non-Malays alike, with each community having their own interpretation of the dish. The Malay version is usually served “dry” with little curry or gravy, topped with fried chicken or fried fish and a fried egg. The Chinese version is often complemented with chicken sausages, a fried chicken drumstick, fish cakes, luncheon meat and curried vegetables.

Associated Social and Cultural Practices

The recipes and the knowledge and skills for preparation of nasi lemak is passed down within families and also between hawkers and their apprentices. Recipes on how to prepare nasi lemak can also be found online.

Preparing nasi lemak requires a few basic steps. First, the rice is washed with cold water to remove excess starch. It is then put into a rice cooker together with water, coconut milk, pandan leaves and ginger. Next, other ingredients like sambal, ikan bilis, egg and peanuts are prepared separately. It is a process that involves considerable manual labour.

Nasi lemak in Singapore usually features less spicy sambal as compared to those from other countries. Mr Abdul Malik bin Hassan, owner of Selera Nasi Lemak, regarded as Singapore’s most famous nasi lemak store, said: “Singapore started off with the same spicy sambal used in Malaysia. But I realised that tourists who visited my store did not dare touch my sambal! We took their feedback and adjusted it so it was sweeter and less spicy.” Mr Abdul Malik knows how important the chili is for nasi lemak. “(Without) the chili is like the body without the soul. You must have the soul inside to move the food,” he said.

Mr Abdul Malik feels that the dish helps him to connect with his Malay community at large. He shared though nasi lemak has always been food associated with the Malay community, it has also become part of the wider culture in Singapore. It is a dish that has become ubiquitous where customers eat it for breakfast, lunch, dinner and supper.

Experience of a Practitioner

Mr Abdul Malik started by helping his family sell nasi lemak packets from a basket in Kampong Siglap in the 1970s and 1980s. His love for cooking did not materialise until the family opened a permanent stall at Adam Road in 1998. However, he shared that the learning process took time. He recalled: “The first time I went to the shop I was tasked to only fry eggs. This went on for a month! My father wanted me break the egg with one hand because the egg white would be thicker.”

From eggs, he went on to fry chicken parts before moving on to cooking the rice and the ikan bilis. Before long, Mr Abdul Malik took over the business from his parents. He expanded the business into a company and offered his siblings shares. The business subsequently turned into a family affair.

Mr Abdul Malik believes what makes his nasi lemak special is the quality ingredients he uses. “My family is very fussy. When you are fussy you cook fussy,” he said. “Our ikan bilis comes from Vietnam, our rice from India, our chicken from Brazil, and our fish from Malaysia.”

Watch: Nasi Lemak

Present Status

Despite the dish’s humble beginnings, the original recipe is constantly evolving. Fads have sprung up locally for a younger generation more open and receptive towards food innovations. In 2017, McDonald’s started selling the Nasi Lemak Burger in July, which was so popular that it was sold out in two weeks. Various restaurants have also started selling their own variations of nasi lemak burgers. Other offerings include nasi lemak pizza, nasi lemak cakes, and even nasi lemak ice-cream.

Nevertheless, nasi lemak’s affordability, availability, and plethora of variations ensures its standing as one of Singapore’s most popular food dishes. Today, it can be found in hotels, cafes, coffee shops, food courts, hawker centres and even at weddings.

To pass on the trade to the next generation, Mr Abdul Malik is teaching his children the same skills his father taught him. The biggest challenge, he shared, is getting quality raw ingredients from his preferred sources which he firmly believes play a vital part in the dish’s taste and popularity. Mr Abdul Malik is confident that nasi lemak will remain a part of Singapore’s food culture. He believes that as long as the basic ingredients (coconut-infused rice, chilli, cucumber, and egg) remains, the dish will continue to stand the test of time.

References

Reference No.: ICH-065

Date of Inclusion: March 2019

References

Coombes, Ping. Malaysia: Recipes From a Family Kitchen. London: Weldon Owen, 2017.

Foodspotting. The Foodspotting Field Guide. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2014.

Hoh, Wong Kim. “The story behind the famous Adam Road nasi lemak.” The Straits Times, 31 March 2015.

Kim, Kwang Ok. Re-orienting Cuisine: East Asian Foodways in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Berghahn Books, 2015.

Wan, Ruth Wan and Roger Hew. There’s No Carrot in Carrot Cake. Singapore: Epigram Books, 2010, Foreword.