Text by John Kwok

MuseSG Volume 8 Issue 1 - Apr to Jun 2015

On 28 January 2015, the National Heritage Board (NHB) announced the activities planned for the commemoration of the 73rd anniversary of the fall of Singapore. The guided tours to the Attap Valley Bunker attracted a lot of attention from the media and the general public. This is because the bunker is sited on restricted land and it was the first time a guided tour could be organised to take the public through the pre-war military structure constructed by the British to transform Singapore into an impregnable fortress. This was made possible through the efforts of NHB, Singapore Land Authority (SLA) and Singapore Police Force (SPF). The guided tour would take participants inside the well-preserved bunker, an unprecedented move. But the larger story surrounding the Attap Valley Bunker may be that there are still other similar sites that have been “forgotten” and are waiting to be found.

The Singapore Naval Base and the Armament Depot

The Attap Valley Bunker’s original name was a simple one: Magazine No. 4. It was part of a network of 18 underground bomb-proof storage bunkers connected by a metre-gauge railway line. These 18 bunkers made up the Armament Depot of the Singapore Naval Base. The Singapore Naval Base was the key component to a British defence plan to protect all British colonies from Hong Kong to Burma. The plan was dubbed the “Singapore Strategy”, and it led to the construction of a modern naval base in Singapore capable of providing anchorage and maintenance for the largest of the British warships.

In the event of trouble in the region, selected ships from the Atlantic and the Mediterranean would be reorganised and dispatched to Singapore. The Singapore naval base would serve as command headquarters and port for Royal Navy ships that operated in the region. The outbreak of war in Europe and in the Mediterranean in 1939, however, meant that no Royal Navy warships could be spared for operations in Singapore. When Japanese forces threatened British interests in Malaya and Singapore, the British sent only a token force of two capital ships in December 1941 to Singapore — the HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse — along with an escort of four destroyers to deter the Japanese Imperial Navy. The warships made a brief stop at the Singapore Naval Base before they were deployed to search and intercept Japanese forces along the east coast of Malaya. The Japanese sunk the warships, and the British were left with a modern naval base but no fleet.

The dockyards of the Singapore Naval Base survived the Japanese occupation and Singapore’s modernisation after independence. The fate of the Armament Depot of the Singapore Naval Base was less well-known to the general public. After the Japanese occupation, the British returned to Singapore and took over the Singapore Naval Base, using it to support British operations in the region. As part of an agreement to withdraw all British forces from Singapore, the Armament Depot was handed to the Ministry of Defence (MINDEF) after the British withdrew in September 1971. The site continued to operate as a depot until 2002 when it was decommissioned. All the structures that once made up the depot — including the underground storage bunkers — were demolished in phases before the site was handed back to the State. Magazine No. 4 was one of the last surviving underground ammunition stores.

The First Tour

On 7 February 2015, two busloads of Singaporeans were taken to a remote spot along the north coast of Singapore. The location was not far from the Senoko Fishery Port. The bus travelled past an old iron gate topped with barbed wire. After travelling on a winding stony trail, the bus reached the coastline. Everyone was instructed to get of the bus. There was jungle everywhere and it did not feel like Singapore anymore. This was the start of NHB’s first guided tour to the Attap Valley Bunker.

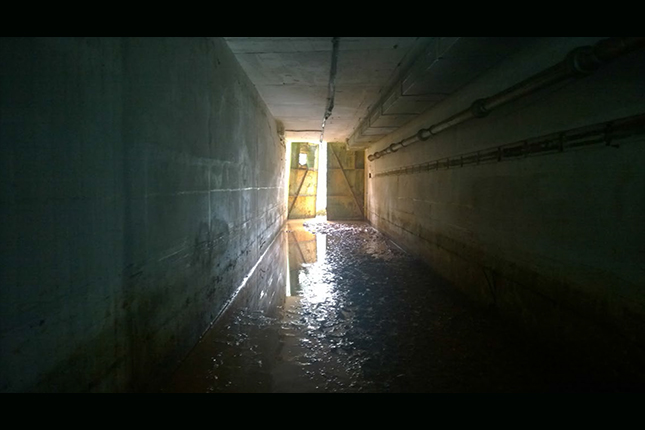

The Attap Valley Bunker is located at the foot of a hill once known as Talbots Hill, which also housed six similar underground bombproof stores that no longer exist. The tour started at the entrance of the bunker, which was a few minutes’ walk along a dirt path from where the visitors disembarked. A set of rusty double metal doors partially blocked the entrance to a long corridor. The tour participants had to wade across ankle-deep mud and water along the corridor to reach the storage area. The corridor, lit only by the participants’ torchlights, led to a cavernous storage space of nearly 300 square metres.

There were two gantry cranes installed inside the storage space, and each crane had a loading capacity of one and a half tonnes. Metal plates welded on the crane showed that they were manufactured and supplied by Marshall Fleming & Co Ltd in 1937. Signboards reminding operators of the crane’s loading capacity were later installed on the cranes, which indicated that the cranes were still in use after the war. The tour participants were given the opportunity to explore the bunker on their own before they were guided back along the same muddy, flooded corridor to the bunker’s entrance. By the end of February, 11 groups of Singaporeans had visited the Attap Valley Bunker on NHB’s guided tour programme.

Finding ‘Forgotten’ Sites in Singapore

The 11 guided tours to the Attap Valley Bunker were part of NHB’s commemorative programmes for the 73rd anniversary of the battle for Singapore and the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Singapore. The aim of the tours was to share NHB’s research on pre-war and wartime sites and structures that are lesser-known to Singaporeans. Participants on the tour were baffled by the fact that a large site like the Attap Valley Bunker still existed in a highly urbanised Singapore. The question most asked by participants on the tour was if there were still more sites like Attap Valley Bunker waiting to be discovered and documented. NHB’s work in 2014 researching and documentingthe Keppel Hill “forgotten” reservoir, remnants of the 1887 New Lunatic Asylum wall and the Marsiling Tunnels suggests that there are still more sites waiting to be discovered. The question is why.

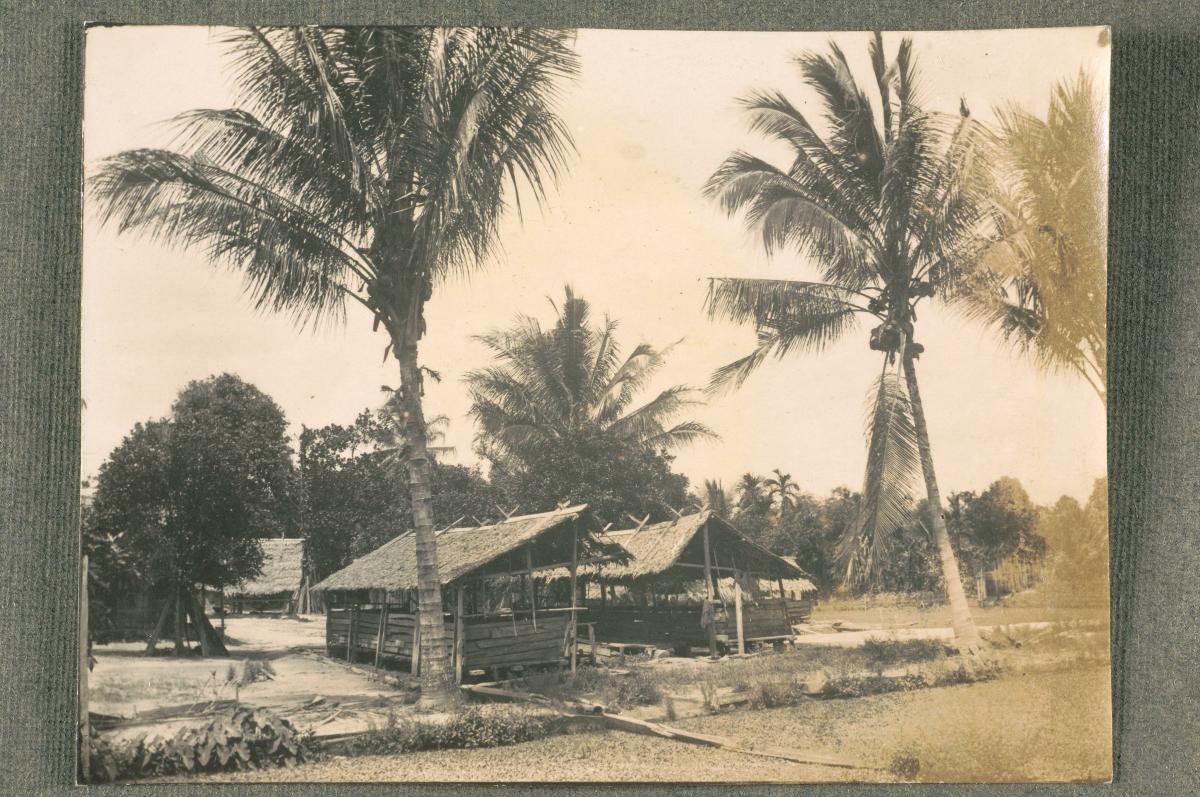

Singapore was a British colony and development of the island during the colonial period reflected this. All major government buildings were located inside the city district, which was fairly well-defined. When viewed through the eyes of the British and locals, colonial Singapore had a real frontier, which stretched from the edges of the city district to the coastline. This was rural Singapore. Plantations, farms and kampongs shared this rural space with British military camps and installations, as well as infrastructure buildings such as fuel and water storage facilities. As the city core expanded, it pushed its periphery to the physical edges of the island, absorbing and colonising what was once Singapore’s rural space. Buildings and sites in the rural areas were either torn down or abandoned to make way for urban development.

There are no more physical frontiers on mainland Singapore today. NHB’s research efforts uncovering the Keppel Hill Reservoir, the 1887 New Lunatic Asylum wall and the Attap Valley Bunker reveal Singapore’s old frontiers and layers of the past. These historical sites offer a way to look at Singapore through the eyes of the British who planned the development of the island as a colony. In tracing the development of Singapore’s frontiers, we are reminded of the many layers of the past we stand on. As the nation continues to develop, we will uncover more layers of Singapore’s past, strengthening our identity and enriching the Singapore story beyond SG50.