When Dr Lai Ah Eng was a little girl, one of her teachers insulted her and her friends for being poor. “You girls will never eat cream,” the teacher said. “You will only eat cow dung.”

Her father had migrated to Malaysia from Hainan Island in China around the year 1930. He was so poor and uneducated, he did not even know how to read or write. Luckily, he was able to make a living by running a kopitiam, or coffee shop, in the city of Kuala Lumpur.

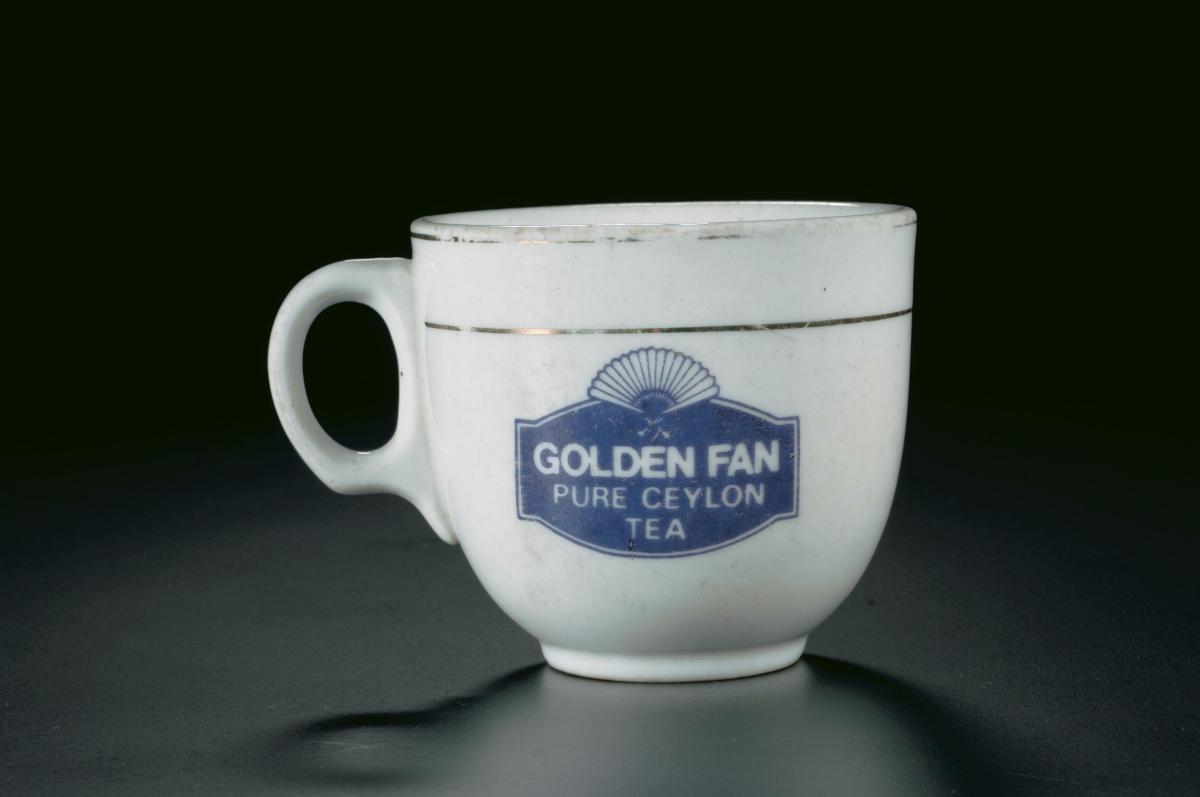

Every morning, he would wake up at five o’clock to light a fire in the oven, slice the bread, and prepare coffee for his customers. People would begin arriving just before six to hear the first broadcasts on the Rediffusion radio station.

Growing up

Growing up in the sixties, Dr Lai was able to study at the free school nearby. But, after classes, she had to help out with the business, together with her mother and four sisters. She would try to do her homework at the counter, when she did not have to wash the cups and spoons, sell cigarettes, and sweep the floor before closing. Usually, they would not finish work until ten or eleven at night.

At first, she hated the work. She secretly made a promise to herself: “I’ll never marry someone who runs a coffeeshop!” But, after some time, she began to appreciate how important the place was. It was a place for the community to gather and enjoy cheap, good food while listening to the news on the radio.

It was also a very multicultural place. Besides their own bread and coffee, they sold nasi lemak and pisang goreng, made by a Malay neighbour. Sometimes, people set up their own food stalls beside the shop, including an Indian woman who sold appam and a Hakka woman who sold laksa.

At one point, developers bought the land and announced that they would demolish the shophouse. “My father was so depressed, his hair suddenly turned white in one month,” Dr Lai remembers. Thankfully, an Indian man across the street offered to let the family take over his shop, free of charge, because he was returning to India.

A training ground

Today, Dr Lai is a professor at the National University of Singapore. She is an anthropologist: a person who studies human societies and cultures. She suspects that working at her father’s kopitiam was good training for the job. It was a centre of activity and a window to the world.

Five years ago, she was part of a team of researchers studying migration. Most of her colleagues were focusing on new immigrants to Singapore. She, on the other hand, decided to look at how older immigrants had become part of our community. She did this by studying the history of kopitiams.

She learned that many early kopitiam owners were Hainanese, just like her father. For instance, the famous Ya Kun Kaya Toast business was originally a food stall set up by Loh Ah Koon, a Hainanese immigrant who came to Singapore in 1926 when he was just 15 years old. Jack’s Place, Han’s and Killiney Kopitiam were all also founded by Hainanese people. The cooks served Asian versions of western foods, such as toasted bread and pork chops, because many of them had worked as servants in British homes.

But, it was not only the Hainanese who ran food stalls. Immigrants from other parts of Asia did the same thing. In 1924, a man named Bhavan from India set up Ananda Bhavan, which is now a vegetarian restaurant chain. In 1958, a Sumatran immigrant set up Sabar Menanti, which still sells nasi padang in Kampong Glam.

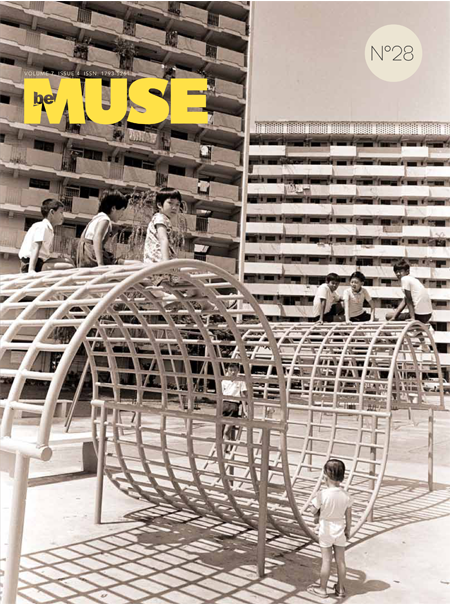

Our kopitiam heritage

From the 1960s to the 1980s, the Housing Development Board (HDB) began to move people from kampungs into public housing estates. They also opened new kopitiams in these areas, bringing together stallholders and customers of different races. “The kopitiam naturally became one of the first public gathering sites for those disoriented by resettlement,” Dr Lai says. Old friends could meet there and also make friends with their new neighbours. They also began to enjoy each other’s foods, giving birth to the multicultural Singaporean cuisine that we know today.

However, these kopitiams are now under threat. Previously, neighbourhood kopitiams were mostly owned by stallholders. But, since 2001, many kopitiams have been taken over by chain operators such as Koufu, S11, Food Republic and Kopitiam.

These businesses often renovate the spaces, charge higher rents, and then sell them again to make a profit – sometimes just after a few years, or even months! As a result, the rents for stallholders keep going up. Because of the expense, many stalls are closing.

We, Singaporeans, are proud of our kopitiam heritage. This is why Ya Kun and Killiney use nostalgic items like wooden stools in their shops, to bring back memories of the “good old days”. But, big businesses are making it almost impossible to succeed as a stallholder now. Dr Lai notes that if her father had migrated in modern times, his business would never have been able to survive.

The Government is working to address the current situation. They have stopped allowing sales of their newly built kopitiams, and only rent out them to operators to help keep costs reasonable. But, we should do more so that our beloved kopitiams may be enjoyed by future generations of Singaporeans.

-by Ng Yi-Sheng

This article first appeared in What's Up, a newspaper that explains current affairs in a way that children find comprehensible and compelling.