TL;DR

A stroll along the banks of the Singapore River offers a picturesque journey through 200 years of the city’s modern history: from its 19th century colonial civic district at the river mouth through various ethnic enclaves. The bridges connecting the two riverbanks serve different purposes: some provide accessibility to pedestrians crossing over, while others function as throughfares for vehicles. In 2019, the three historic bridges closest to the river mouth - Anderson, Cavenagh, and Elgin Bridges - were gazetted as National Monuments, recognising their significance as symbols of Singapore’s exponential growth as a trading port during the latter half of the 19th century. This essay examines the impact these bridges’ construction had on the bustling river traffic.Improving the Connectivity of Singapore’s Economic Lifeline

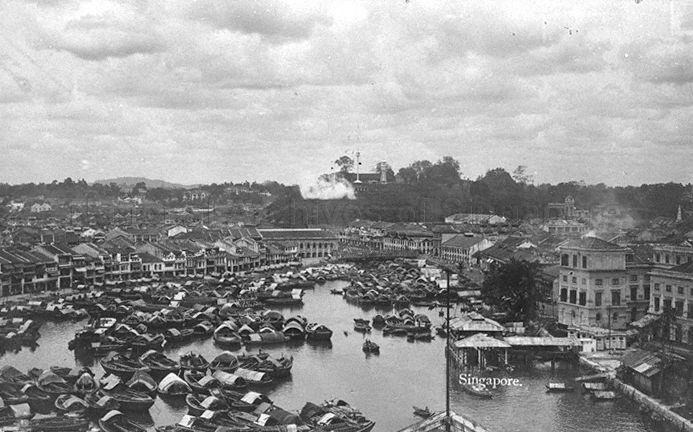

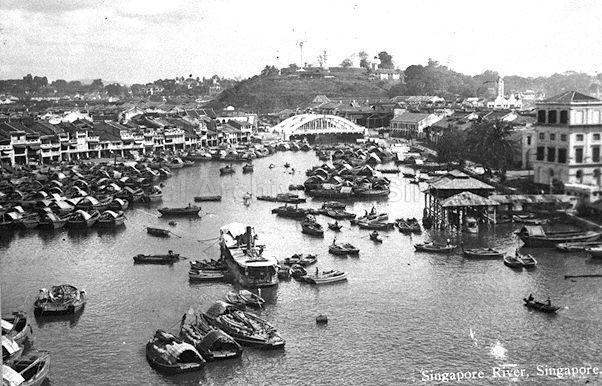

The Singapore River’s economic importance in 19th-20th century Singapore stemmed from its connection to the natural harbour. Chinese silk, Javanese spices, Indian cotton, and Sumatran pepper were traded and transported along its quays. By the 1860s, three-quarters of Singapore’s shipping business concentrated on the river, with godowns, rice mills, and boatyards lining the riverbanks to support its growing entrepôt industry.[1]

Seasonal monsoons dictated trade rhythms, with activity peaking from November to March as ships from China and Europe arrived laden with goods. Oceangoing ships transferred up to 30 tons of cargo per trip to lighterboats - called tongkangs and twakows, depending on their Indian or Chinese origins.[2] The 1869 opening of the Suez Canal accelerated trade between Europe and Asia, attracting over 500 ships monthly to Singapore. By the 1890s, the river handled more than 500,000 metric tons of cargo annually.[3]

Keeping the river traffic open was vital to Singapore’s economy in the 19th century, yet disruption to river traffic was inevitable during the construction of the bridges. Thankfully, as construction technology advanced from the late 19th to early 20th century, disruptions were significantly reduced from months to mere days. The three historic bridges - Cavenagh, Anderson, and Elgin - completed in 1869, 1910, and 1929 respectively, stand as testament to the rapid advancement in structural engineering and material innovations at the turn of the century.

When Traffic Stood Still for Cavenagh Bridge’s Construction

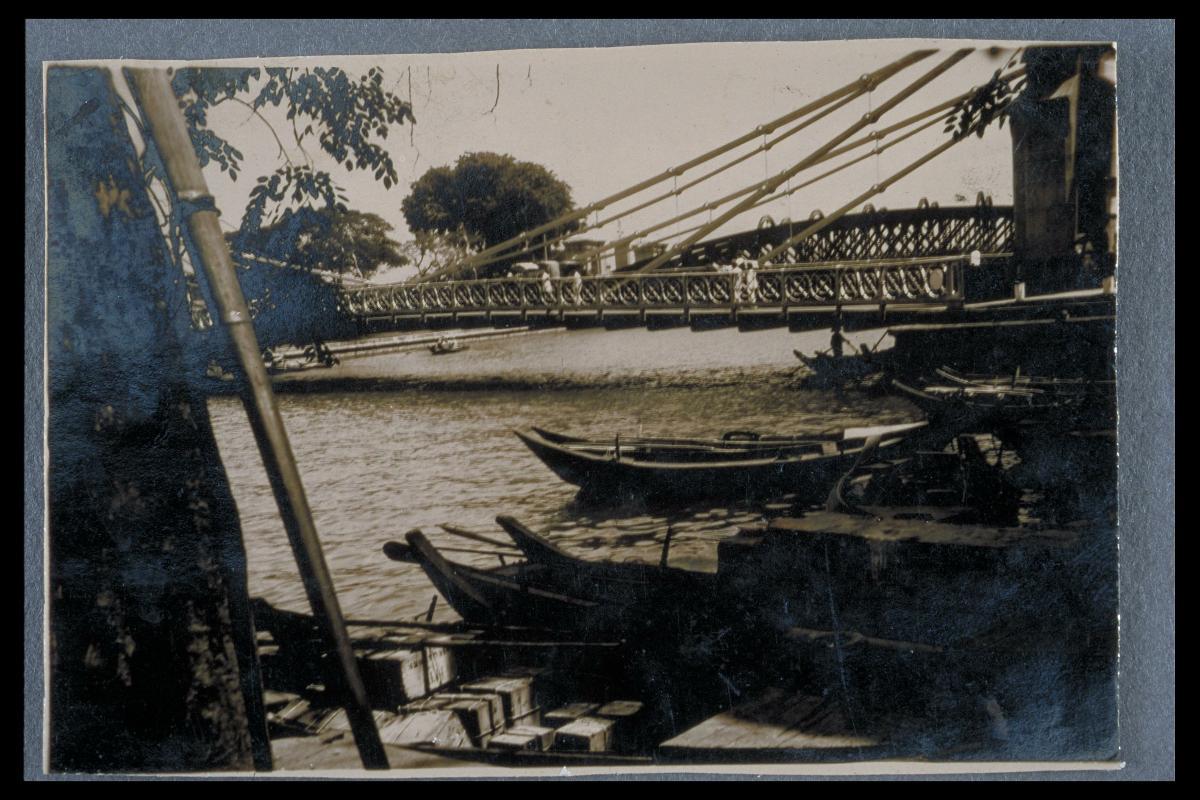

The cable-stayed Cavenagh Bridge’s design required its iron bridge deck to be constructed before chain links, made of short segments of wrought iron plates, could be riveted to the deck and anchored to four masonry pylons.[4] During the three-month construction from April to July 1869, workers erected staging across the river mouth, supported by multiple timber piles driven into the shallow waters of approximately of 2.6 metres depth.[5]

In the early days of construction, the staging and the bridge deck suffered from constant “striking and bumping by large and heavily laden lighters.6 This frustrated the Municipal Engineer, Arthur H. De Wind, who ordered the closure of the river near the bridge. River traffic was reduced to “an opening on either side of the cofferdams for boats of light draft, not more than two coyans[7].” This effectively halted lighterboat operations[8] weighed at least 5 tonnes (2 coyans), and more than 30 tonnes (12 coyans) when fully loaded.[9]

The disruption ceased upon Cavenagh Bridge’s completion. A live load testing was conducted by “a party of 120 Sepoys soldiers marching over the completed Cavenagh Bridge”.[10] Satisfied with its ability to withstand the load and movement of pedestrians, bullock carts, and carriages, De Wind certified the bridge safe for use. The Municipal Commissioners immediately ordered the removal of staging and restored “free navigation of the river.”[11]

New Technologies in Anderson’s Bridge Installation

Learning from the experience of Cavenagh Bridge, river traffic disruption during the construction of Anderson Bridge was reduced to just one week. The process involved constructing a track system, installing girders, and subsequent dismantling. The approach was possibly influenced by Robert Peirce’s experience with the Read Bridge in 1888.

Construction work occurred in two phases. First, workers assembled three bowstring arch girders “on the vacant grounds on the north side of the river”,[12] roughly where Empress Place Green stands today. Concurrently, local contractors Messrs Howarth Erskine built a temporary track system for hauling the girders across the river. The system comprised five pairs of supporting piers driven into the river bed, with steel joists placed between each pair. These supported three pairs of longitudinal rails for bogies run on, pulling each arch girder into position.[13] A “13-horse power winding engine coupled to a steel wire rope” hauled the three arch girders, each weighing more than 250 tonnes.[14]

At 6am on Sunday, 4 April 1906, after weeks of preparation the girders were slowly hauled across the river from the North Bank.[15] This timing minimised disruption, as river traffic had to be completely closed during the move. The downstream girder was hauled first to its intended position, followed by the upstream girder and then the heavier 300-ton central girder.[16] A subsequent municipal report praised the “very little interruption to the river traffic” and explained why this method was chosen over “floating the girders across the river.”: morning low tide would have prevented pontoons from lifting girders off the northern bank, and Municipal Engineer Robert Peirce had designed the girders’ erection “to be largely effected on terra firma” to minimise river disruptions.[17]

Floating the Assembled Bridge

By 1928, bridge engineering had advanced significantly. Elgin Bridge’s designer, T.C Hood, had several construction and installation methods at his disposal. Though the bridge structure “could have been done by laying the massive steel girder separately across the river” similar to Anderson Bridge,[18] he opted to “draw the steel bridge across as one complete structure.” This decision stemmed from the realisation that floating the entire bridge would affect river traffic for a day or less.[19]

As with Anderson Bridge, British manufacturers Glasgow Steel Roofing Company produced the steel components, which were assembled on land. A 1928 postcard of Boat Quay captured the bowstring arched bridge’s assembly on the open space on the north riverbank, forming a steel structure 146 feet (44m) long, 80 feet (24m) wide and 30 feet (9m) tall.[20]

On the afternoon of 30 October 1928, river traffic halted for Elgin Bridge’s installation. Workers lashed two hopper barges, fashioned from tongkangs, together to form a pontoon. During low tide, the pontoon was “moved into position below the overhanging steelwork.”[21] As the tide rose, the water slowly raised the pontoon until it contacted the steelwork. One end of the steel structure slowly lifted off its supports as the pontoon transported it towards the south riverbank.[22] Workers used cables and winches to guide the structure slowly to its final position on the granite abutment. By evening, as the tide level subsided, Elgin Bridge settled into position.[23]

Over the following seven months until its official opening on 30 May 1929, workers encased the steel bridge structure in concrete to improve its strength for heavier vehicular traffic.[24] Hood designed this concrete encasement to also protect the steel from corrosive “sulpheretted hydrogen” released by numerous riverside industries.[25]

Stories of Economic Development Behind Our Heritage Bridges

The appreciation of heritage sites often focuses on age, historical significance, and aesthetic values. Yet a deeper understanding of century-old infrastructure, focusing on functional utility, structural design, and even the construction process, could turn up interesting observations of the economic environment and technological progress of different time periods.

Studying these three historical bridges’ construction history draws attention not only to the structures themselves, but also to their intimate relationship with the Singapore River and the countless lighterboatmen, coolies, and others whose livelihoods depended on the river throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

Notes

[2] Stephen Dobbs, ““Tongkang, Twakow," and Lightermen: A People's History of the Singapore River,” Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 9, No. 2 (1994): 272 – 3. https://www.jstor.org/stable/ 41056890

[3] Wong Lin Ken. “Singapore: Its Growth as an Entrepot Port, 1819 – 1941.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 9, no.6 (1978): 59. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S002246340000953X

[4] “The New Bridge,” The Straits Times, 5 April 1909, 7.

[5] Port of Singapore Authority, Hydrologic Chart of Singapore River, scale 1:2500, 1993, HC000510, Collection of Hydrographic Department, National Archives of Singapore.

[6] “Municipal Council,” The Straits Times, 17 April 1869, 2.

[7] A coyan is a unit of mass used in colonial Singapore and the wider Straits Settlements in the 19th and 20th century. 1 coyan is approximately 2,400 – 2,500kg (5,300 lbs).

[8] C. A. Gibson-Hill, “Tongkang and Lighter Matters”, Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 25, No. 1 (1952): 88 - 89. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41502936.

[9] Ibid

[10] “Untitled,“ Straits Times Overland Journal, 26 Oct 1869, 13,

[11] “Municipal Engineer Report,” The Straits Times, 31 July 1868, 2.

[12] “Interesting details of Anderson Bridge’s new structure,” The Straits Times, 20 Aug 1909, 7.

[13] “First girder placed over the river,” The Straits Times, 5 Apr 1909, 7.

[14] ibid

[15] ibid

[16] ibid

[17] ibid

[18] “The New Elgin Bridge Nearing Completion,” Malayan Saturday Post, 3 Nov 1928, 36.

[19] “Erection of Elgin’s Superstructure,” The Singapore Free Press, 31 Oct 1928, 11.

[20] “Elgin Bridge Problem,” The Straits Times, 28 Oct 1929, 11.

[21] ibid

[22] “Erection of Elgin’s Superstructure,” The Singapore Free Press, 31 Oct 1928, 11.

[23] ibid

[24] Municipality, Singapore, Administration Report of the Singapore Municipality for the Year 1929, F-2.

[25] “Singapore River Smell Corrodes Bridge,” The Straits Times, 17 Apr 1939, 13.

.ashx)

.ashx)